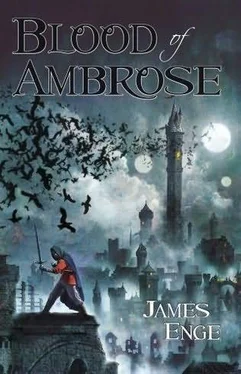

James Enge

Blood of Ambrose

The first book in the Ambrose series

PART ONE: ARMS OF THE AMBROSII

Marshal, demand of yonder champion the cause of his arrival here in arms. Aak him his name and orderly proceed to swear him in the hustice of his cause.

– Shakespeare, Richard III

The King was screaming in the throne room when the Protector's Men arrived. He knew it was wrong; he knew he was being stupid. But he was frightened. When the booted feet of the soldiers sounded in the corridor outside, he belatedly came to his senses. Dropping to the floor, he crawled under the broad-seated throne where the Emperor sat in judgement, next to God Sustainer. (Only there was no Emperor now, and Lord Urdhven, the Protector, made his judgements in his own council chamber. Did the Sustainer dwell there now? Or still upon the empty throne? Was there really a Sustainer? Would the Protector's soldiers kill him, like all the others?)

He pulled in his legs just as the soldiers entered the room, their footfalls like rolling thunder in the vast vaulted chamber. He'd hoped they couldn't see him. (Would God Sustainer protect him? Was there really a Sustainer?) But the soldiers made straight for the throne.

If the Sustainer was not with him (and who could say?), the accumulated precautions of his assassination-minded ancestors were all around. As he pressed instinctively against the wall behind the throne, it gave way and he found himself tumbling down a slope in the darkness. Briefly he heard the shouting voices of the soldiers turn to screams and then break off suddenly. Because the passageway had closed, or for another reason? His Grandmother would know; he wished she were here. But she was far away, in Sarkunden- that was why the Protector had moved now, killing the family's old servants like pigs in the courtyard….

He landed in a kind of closet. There were cloaked shapes and bits of armor lying around in the dust that was thick on the floor. Perhaps they were, or had been, things to help an endangered sovereign in flight or self-defense. He thought of that later. But just then he only wanted to get out; by flailing around in the dark he found the handle of a door and plunged out into the bright dimness of a little-used hallway.

Hadn't he been here before? Hadn't Grandmother told him to come here, or someplace like here, if something happened? He hadn't been listening. Why listen? What could happen in the palace of Ambrose, with the Lord Protector guarding the walls …? And they had cut his tutor's throat, cut Master Jaric's throat, and hung him upside down to drain, just like a pig. He had seen it once at a fair, and Grandmother had said he must never, never do that again.

The sudden memory renewed his terror; he found himself running down the corridor in the dim light, the open doors on either side of him yawning like disinterested courtiers. There was a statue of an armed man standing over a broad curving stairway at the end of the halt. The King was almost sure Grandmother had mentioned a place like this, but without the statue. If he went down the stairs, perhaps that would be the place, and he would remember what Grandmother had told him to do next-if she had told him.

But as he passed the statue it moved; he saw it was not a statue-no statue in this ancient palace would be emblazoned with the red lion of the Lord Protector. The Protector's Man reached for him.

The King fell down and began to scuttle away on all fours, back down the corridor. The Protector's Man dropped his sword and followed, crouching down as he came and reaching out with both hands.

"Now, Your Majesty," the soldier's ingratiating voice came, resonating slightly, through the bars of his helmet. "Come along with me. No one means to harm you. Just a purge of ugly traitors who've crept into your royal service. You can't go against the Protector, can you? You found that out. And stop that damned screaming."

The King was screaming again, weary hysterical screaming that made his body clench and unclench like a fist. Looking back, he saw that the soldier had caught hold of his cloak. There was nothing he could do about the screaming, just as there was nothing he could do about the soldier.

Then Grandmother was there, standing behind the Protector's Man, fixing her long, terribly strong hands about his mailed throat. The soldier had time for one brief scream of his own before she lifted him from the floor and shook him like a rag doll. After an endless series of moments she negligently threw him down the hall and over the balustrade of the stairway. He made no sound as he fell, and the crash of his armor on the stairs below was like the applause that followed one of the Protector's speeches-necessary, curt, and convincing.

Before the echoes of the armed man's fall had passed away, Grandmother said, "Lathmar, come here."

Trembling, the King climbed to his feet and went to her. Grandmother frightened him, but in a different way than most things frightened him. She expected so much of him. He was frightened of failing her, as he routinely did.

"Lathmar," she said, resting one deadly hand on his shoulder, "you've done well. But now you must do more. Much more. Are you ready?"

"Yes." It was a lie. He always lied to her. He was afraid not to.

"I must remain here, to keep them from following you. You must go alone, down the stairway. At the bottom there is a tunnel. Take it either way to the end. It will lead to an opening somewhere in the city. Go out and find my brother. Find him and bring him here. Can you do that?"

"How …? How …?" The King was tongue-tied by all the impossibilities she expected him to overleap. He was barely twelve years old, and looked younger than he was, and in some ways thought still younger than he looked. He was aware, all-too-aware, of these deficiencies.

"You know his name? My brother's name?"

"His name?" the King cried in horror.

"Then you do know it. Say it aloud. Say it to many people. Say, 'He must come to help Ambrosia. His sister is in danger.' By then I will be, you know."

The King simply stared at her, aghast.

"He has a way of knowing when people say his name," the King's Grandmother, the Lady Ambrosia, continued calmly. "That much of the legend is true. But more is false. Do not be afraid. Say the name aloud. You are in no danger from him; he is your kinsman. He will protect you from your enemies, as I have done."

From the far end of the corridor echoed the sound of axes on wood.

"I had hoped to go with you," his Grandmother continued evenly, "but that will not be possible now. You will have to find someone else to help you; I wish you luck. But remember: if you do not find my brother, I will surely die. Your Lord Protector, Urdhven, will see to it. You don't wish that, do you?"

"No!" the King said. And that, too, was a lie. It would be a relief to know he had failed Grandmother for the last time.

"Go, then. Save yourself, and me as well. Find-"

Knowing she was about to say the accursed name, her damned brother's name, he covered his ears and ran past her, skittering down the broad stone steps beyond. He passed the corpse of the fallen soldier. He kept on running.

By the time the light filtering from the top of the stairway failed, he could see a faint yellowish light gleaming below him. When he reached the foot of the stair, he found a lit lamp set on the lowest step.

His feelings on reaching the lamp were strong, almost stronger than he was. He knew that his Grandmother had set it here to give him not only light, but hope. It was a sign she had been here, that she had made the place safe for him, that he need not be afraid. As he lifted the lamp, he felt an uprush of strength. He almost felt he could do the task his Grandmother had set him. He swore in his heart he would succeed, that he would not fail her this time.

Читать дальше