"You're Aurelius, I bet," I said.

"You win the bet," he said. He didn't rise but gestured at a chair and said, "Won't you sit down? My people will bring you something."

"Your-" I said, sitting across from him.

He rapped his knuckles, and a blue-and-white-clad servant appeared from a door I hadn't noticed in the wall of the hostel behind Aurelius.

"Would you like something to eat? Something to drink?"

"Not until I know what this is about."

He laughed and said, "Tea for me, Zyrn. Bring two cups, in case she changes her mind." The servant stepped back into the doorway and disappeared.

"What's your interest in Morlock?" I asked. "And why are you bothering me about it?"

He didn't answer. He looked at me assessingly and after a moment said, "I suppose I can see it. You resemble Morlock's wife somewhat: a crude copy of a more sophisticated original-"

"His wife?" I snapped, nearly jumping out of my chair. I'd had no idea Morlock was married. It seemed as odd as a tree stump or a broken boulder being married.

"Well, ex-wife," Aurelius conceded. "His exile from the Wardlands technically dissolved the union. But I'm a little old-fashioned, and I don't think these bonds are so easily broken. I see he didn't tell you about her. Well, maybe that's not significant. He doesn't talk much, does he?"

"What's this about?" I demanded. "What are you getting at?"

"I'd rather go at this slower," Aurelius admitted, "but I realize you don't have all day. I am interested, as you put it, in Morlock for a number of reasons, but the most urgent one is that he's trying to kill my wife. I'm bothering you about it because he's already killed one of your sons and may succeed in destroying your entire family."

What he said about my family was so like what I feared that I froze for a moment. But I didn't want to give him a single clue how close to my heart he had struck, so I said, as calmly as I could, "My son was killed by the Khroi. Morlock wasn't even present at the time. I was, though, and there was nothing I could do about it. Thanks for reminding me, you heartless bastard."

"I'm sorry," he said, with every appearance of regret. "Really I am. I'm trying to appeal to you through your wounded heart because we have a common interest, a desperately serious one. I ask you to think about this painful subject only to avoid more pain for yourself and your family. Of course the Khroi killed Stador, but who was really responsible? The Khroi aren't much more than animals. Why were you in that mountain pass? Would you ever have gone there but for him? And now your son is dead."

"You don't give a damn about my son. About any of us."

"That's true, in a way," he admitted cheerfully. "You're nothing to me. But my wife is. We can help each other. We must help each other. We must save what we can of the people we love."

I met his blue eyes and, Strange Gods forgive me, he looked earnest. More than that: honest. Like I could trust him. And I wanted to believe him. It let me off the hook, you see. Morlock had warned us and warned us that the Kirach Kund was dangerous, and we hadn't listened to him. Of course, he hadn't given us all the details. If he had, we would have chosen differently, of course. Of course we would have. That made it his fault, not ours. It had to be that way. It had to be that way, because if Morlock wasn't responsible, then we were. Or, more precisely, I was. I had killed my son.

I said nothing as all of this was chewing through my brains. Zyrn, the blue-and-white-clad servant, brought the tea and vanished again, without Aurelius so much as looking at him. The old man poured us each a cup of tea, sweetening his own with honey and milk from jars on the table and leaving mine black. We both drank. The cups emptied and Aurelius refilled them.

"How did you know I didn't take honey or milk?" I asked. It wasn't important to me; I just felt the silence had to be broken.

He bent forward eagerly. "The same way I knew you would ask that. The same way I knew you would have to shop in Aflraun today. I read it in my map of the future."

"Oh?" I said faintly.

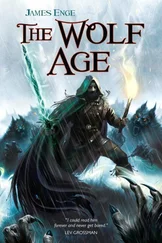

"Yes, indeed." He reached inside his heavy white cloak and drew forth a rolled-up sheet of some kind of heavy paper. He reminded me a little of Morlock at that moment: the crooked man's clothes were full of odd pockets and things.

Aurelius moved the teapot aside and spread the sheet out on the table. It was filled with odd lines of different colors. The lines were in motion, tangling with each other, untangling. I realized suddenly that they were sinking deeper into the paper, as if it were a box, and rising out of it. I blinked a few times and looked away, feeling dizzy.

"It's a little unsettling at first, isn't it?" Aurelius said eagerly. "It's all due to my new scholium of teleomancy. What is the future, except the actions we will take in the future? And we will take those actions because of certain intentions; nobody does anything for no reason. And all those future intentions are rooted in our present concerns. If we could sample the intentions of a significant number of people in a community and trace how they would interact, we could foretell the future with a certain amount of accuracy."

"Without using the Sight," I said.

"Yes." He seemed not to want to talk about that, but he went so far as to add, "The visions of two seers can overlap, you see, and one will know what the other knows. Where's the advantage in that?"

A knowledge-hoarder. I knew the type: almost everyone who has a little magical knowledge hides it in his gown until he can spring it on someone and get something for it. Aurelius all of a sudden seemed less like Morlock. If you expressed the slightest interest in Morlock's latest wonder-working, he would tell you about it until your ears got sore; it was the one thing that made him verbose.

That meant Aurelius was telling me because he expected to get something out of it. I considered the possibilities and finally said, "You're telling me this to impress me. You can do something Morlock can't."

"Oh, so many things!" Aurelius cried out, his wrinkled face filled with a boyish enthusiasm. I wondered how old he was, really.

"And you want me to help you against Morlock," I added.

"I do," he agreed. "For my sake, and for the sake of my beloved wife. And I think you will, too, for the sake of your family. It's suffered so much. Why need it suffer any more?"

It was a strong argument with me. I pick my loyalties carefully, and anyone outside the line has to look out for themselves. There was definitely a line between Morlock and my children. But there was a line between Morlock and Aurelius, too: I didn't know Aurelius, except that he frankly wanted something from me. I had no real reason to trust him.

"No," said Aurelius deliberately. "You don't."

I looked up. His eyes were on the squirming lines of his map. He raised his gaze slowly and smiled at me.

"You've sampled me," I said. "You have a window into my intentions."

"Yes, Naeli, I took that liberty the last time you crossed Whisper Street to get to the marketplace."

"But you haven't sampled Morlock's."

"Oh, but I have. I did it some months ago, before you knew him, I believe." His face fell as he continued, "I almost had him in my grip, then. But he …he had help and got away."

"Good for him."

"Yes," Aurelius replied wearily, "good for him. I am an evil old man who wants his wife to outlive him, and Morlock is the shining sacred hero who would make that impossible. Have it as you would like. The question is what you will do, what you are willing to do, to protect what remains of your family. You could have saved Stador: not in the Vale of the Mother, indeed, but by keeping him away from there, by taking another path. The powers surrounding you are immense, Naeli: I show you this"-he gestured negligently at the strange map that he was so proud of-"merely to give you a sense of that. You must use foresight to walk between the dangers safely, to protect yourself and the people you care about."

Читать дальше