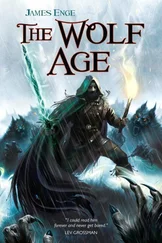

Morlock stood back and unslung his pack. He drew out the choir nexus and unwrapped it. He explained the matter in a single terse sentence; a moment later, fifteen volunteer flames were eating their way into the door around the lock. When they had passed through Morlock cried "Stay clear!" and kicked in the door.

He paused for a moment on the threshold, shuddering with fever chill and pain. (The blood-beats of exertion were agony to his wounded arm.) Then he passed into the entry hall and swore. The flames had stayed clear all right. From burn marks in the many rugs and tapestries it appeared they had scattered in search of adventure and interesting combustibles.

Well, he had no time to look for them. He stowed the nexus in his backpack and took that on his shoulders again. The hallway led him to a winding stairway; Morlock ascended it, feeling that the sorcerer's workroom would be on the upper floor.

It was. In fact, the workroom occupied the entire upper floor of the house. As he entered it, his enemy, at the far end of the long room, rose to greet him.

The room was full of water. It was lit (quite apart from the tall unglazed windows) by glass cylinders filled with a bubbling white fluid that emitted a harsh bluish light; these were set like torches along the walls. The stained worktables that lined the room were crowded with retorts, alembics, beakers, tubes, and tubing, all of them emitting or gathering liquid. In the middle of the room was a circular sheet of gray bubbling water, suspended in midair. At the far end of the room was a crystal globe fill with very bright, very clear water. Morlock guessed this was the sorcerer's focus. At any rate, he was seated before it with a fixed inward stare when Morlock entered the room, and he turned around and smiled broadly, as if in welcome.

"There are flames like rats loose in my house," he explained, rising. "Fortunately they have proven rather easy to detect and extinguish. I hate flames, I suppose as much as you love them. Mine is a watery sort of magic, as you will have guessed."

The stranger advanced through the room as he spoke, his manner suggesting that Morlock was an expected guest and he himself was a slightly remiss host. He wore garments of white and blue; otherwise he was a mirror image of Morlock: the same dark unruly hair, the same weather-beaten features, the same alarmingly pale gray eyes. The stranger even had crooked shoulders and walked with a slight limp, as Morlock did.

"Unimpressive," Morlock remarked. "Certainly not original."

The stranger looked surprised, then amused. "Oh, my appearance. But I assure you, my dear fellow, it is no mere ploy. Years of labor have gone into this work, and perhaps the rest of my life will go into perfecting it. You see, I have decided to usurp your personality."

Morlock shrugged.

"I'm not joking, either," the stranger continued. "Not that I'm surprised by your indifference. That's what gave me the idea, in a way.

"You see, I was sitting in a tavern (forgive my loquacity, but I have so looked forward to telling you all this) and a drunk was singing some nasty ghost story you were supposed to have had a part in. And I was thinking how …well, how unlike your legend you are. (Most of those-who-know know that.) And I thought, too, how little use you have put your legend to. It really is a remarkable resource, coupled with your true abilities. You are truly feared, south of the Kirach Kund. Yet you wander from place to place like …like some kind of magical tinker, when you might command fear and respect the way a general commands an army."

Morlock shrugged irritably. "Why?"

"Why?" repeated the stranger incredibly. "For everything a man could want!"

"There is not much that I want."

"That is your problem. It is not mine. Mine is (or was) that I had no legend. Like most makers, I have pursued my studies in solitude; we are too unworldly, most of us. I would have labored in obscurity, only to totter into some local fame when I was too infirm to put it to effective use. You have the advantage of us there; we aren't all descended from demi-mortals like you are.

"Then I realized (sitting in the tavern, you understand) that if you weren't going to use your legend, it was only fair that I do so. And to that I have bent my life ever since. I built my house here in the winterwood; I changed my appearance; I began to conduct correspondence with other sorcerers in my new person. Things were developing nicely, even before I ran into you along the trail the other night."

"So it was an accident."

"Some such meeting was inevitable," the stranger said superciliously. "Anyway, I managed to slit your pack and extract the book of palindromes (which has proven most instructive, by the way). But the protective spell over your person was so subtle I could not even guess its attributes. So I decided to lure you into my own territory…."

Morlock was smiling wryly.

"I suppose that sneer means there was no spell," the stranger said bitterly. "Well, that doesn't matter. You are here, now, and your pack is here, and there are no risks involved. Or maybe you're thinking I'm an inferior sorcerer because I had to appropriate your legend. But I'm not. Your legend is a historical accident. I can't be held responsible for not being the beneficiary of a historical accident."

"It was political slander, originally," Morlock observed, a little weary of the subject.

"Really? That's most interesting. Take some political slander, let simmer a few hundred years, add seasoning, and dish up. Fearful legend, serves one. Very nice.

"Now arises the question of whether I will spare your life or not. I feel you might possibly be a useful adviser, under restraint-sort of the world's expert on having been Morlock, if you see what I mean. Also, I'm sure some of the most interesting artifacts in your pack would be damaged in a mortal combat. So …"

Morlock said nothing.

"Oh, come now," the stranger said irritably. "Don't try to be forbidding. I know exactly what shape you're in. I watched every step of your journey; don't think I didn't. I knew the forest would do my fighting for me! I saw you scrabbling at the lock on my door (what a pitiful performance that was!) and I see now that you can barely stand.

"And where do you stand? In my place of power. Never doubt it, Morlock: I have a thousand deaths at my beck and call as I stand here. Do you doubt it? You still are silent?" The stranger shrugged. "Very well. Why should you take my word for it?" He waved his hand and spoke an unintelligible word.

The weight on Morlock's crooked shoulders was suddenly heavier by several pounds. In sudden alarm, he unslung his pack and lifted out the choir nexus. Water poured out through the dragon-hide wrapping. The choir was dead.

"You killed my flames," Morlock said hoarsely. His eyes were stung by abrupt surprising tears.

The stranger laughed incredulously. "`Killed'? The notion is jejune. I extinguished them. That water might as easily have gone in your lungs instead, or-heated to steam-in your heart or brain. Then it is you who would have been extinguished. I killed my hundreds perfecting the techniques, Morlock, and they work. Never doubt it-again."

"I doubt you will find your own death jejune," Morlock replied. Tears were still running down his face; he supposed it was a symptom of the fever.

"Don't threaten me, you battered tramp!" the stranger snarled. "You were about to hand me your pack, that I might spare you what remains of your life. Do so now."

A long moment passed, in which Morlock seemed to consider. Then he slowly lifted the pack, holding it out to the stranger.

The stranger laughed and took the proffered edge. This, the only convenient hold, happened to be the place where he had slit the pack two days ago. When his grip was firm, Morlock pulled back, as firmly. The stranger's grip, resisting the tug, tore the gripgrass woven into the sewn seam.

Читать дальше