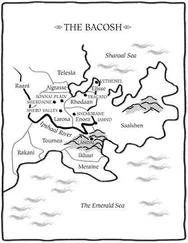

“They must deal with the entire Saalshen Bacosh before attempting Saalshen itself,” said Kessligh, with more confidence than he felt. “That will be no easy thing, even if Rhodaan were to fall.”

“But they’ll never have so many forces mustered for the task as now,” Rhillian said quietly. “They’ll not waste the opportunity, no matter what their casualties. They’ll take the plains as far as the Telesil foothills, as Leyvaan did last time, only they won’t repeat his mistake and march into the forests. Those they’ll take piece by piece, clearing with axes as they go. It may take decades, but Saalshen will die a slow death. We cannot defeat such massed armour on our own.”

If only, Kessligh was tempted to say, Saalshen had built heavy, armoured armies of its own. If only they had been willing to reorganise their society to accommodate such a militaristic change. With serrin, “if only” solved nothing. They were what they were, and change came to them with the utmost difficulty. And perhaps, he had often pondered, in changing to face such a threat, the serrin would lose that very thing that made them so worth defending in the first place.

“I tried my best,” Rhillian said, her voice small. “I tried to keep Rhodaan stable. I do not have a good record of achieving in human society that which I attempt to achieve, but…but I do not see what else I could have done.”

For a moment, Rhillian appeared as Kessligh had rarely seen her-lonely and vulnerable.

“I do not believe you could have done much differently,” Kessligh told her. “Lady Renine and her followers saw the coming war as a chance to retake control of Rhodaan for the feudalists. To place one’s own group above the defence of all Rhodaan is traitorous to say the least, and she got what she deserved. Had you done nothing, the Steel would never have stood for it, and their intervention would likely have placed some general in charge with a far less balanced attitude than yours. The Civid Sein were a nasty complication, and as much a failing of the Tol’rhen and supposedly civilised thinking as anything else. Even I did not see the extent of that problem until it was on top of us. You dealt with each problem in turn, and released the Steel in time to confront the Larosans, with the issue at least temporarily settled. I don’t think you did such a bad job.”

Rhillian gave him a sideways look. “And what do you think to do now?”

“Reorganise what’s left of the Nasi-Keth. Try to keep the peace here in your absence. Hope for the best, and plan for the worst. We shall not let Saalshen fall, Rhillian. Serrin civilisation is the greatest asset that we humans possess. We must save it for our own sake, not merely for yours.”

“A man named Deani was of the same opinion in Petrodor,” Rhillian said sadly. “He was killed when Palopy House was attacked. Justice Sinidane thought much the same. We found him in the cells beneath his Justiciary, tortured and dead of shock. Those who hold such opinions do not live for long, in human lands. And now one of you whom I have loved has run away to the other side.”

“Sasha has not stopped caring,” Kessligh said quietly. “She cares too much. She struggles to decide whom she loves more.”

Sasha sat on a wet stone by the roadside, and waited in the rain. After a while, she heard a single set of hooves approaching. Then, about a bend in the road, a small horse came galloping, ridden by a man in a long cloak. Sasha’s horse looked up at the approach, ears pricked. She seemed to accept Sasha’s calm, and was not unduly alarmed.

The small horse stopped before her, stamping and frothing, and the rider pushed wet hair and hood from his eyes. The left side of his face was tattooed, in a perfect dividing line down brow, nose and chin.

“Identify yourself!” the man demanded, in thickly accented Larosan. Those were amongst the few Larosan words Sasha knew-probably it was the same for this man.

“I am as welcome here as you,” Sasha replied in Lenay, and pulled from her cloak a crimson-and-yellow striped flag. It was the flag of the local House of Neishure, whose riders had escorted her to this point in the morning, proclaiming it the most obvious route to approach Rhodaan.

The outrider stared at her more closely. “Who are you? Have you a name?”

“I do,” said Sasha. “But it is not for you.”

“The King of Lenayin rides this way!” snapped the rider. His accent marked him a southerner. Neysh, perhaps. “I’ll have your name!”

“Come and take it from me,” Sasha suggested. Her face remained hidden beneath the hood. The rider peered further, his horse edging closer. Surely he suspected. But his suspicions would make no sense. He glared at her, and tore off up the crossroad, leaving Sasha alone in the falling rain. After a moment of silence, he came galloping back, having checked that reach and not found an ambush. He waited opposite her, looking back up the road. Soon another rider appeared and the first signalled to him. That man signalled back, plunged his horse into the stream, up the far embankment, and into the forest. Checking for ambush there, too. In case she were a lone spotter. Or a distraction of some kind. Or a lure.

Sasha waited. Two more riders came galloping, and talked to the first, who pointed to Sasha, and the crossroad, his words inaudible. Then he galloped on, and the remaining two split, one up the crossroad, the other across the stream and into the forest at Sasha’s back. Again, she was alone.

After a long while, the rain eased to a drizzle. More riders arrived, and she was similarly challenged. She gave them no more than she had the others. One seemed about to take it further, but another persuaded him otherwise, in furious whispers. They galloped on, save one, who retreated as far as the approaching bend, and awaited the column.

Finally, there came the sound of many soft hooves, horses walking. But many horses. A chink and rattle of armour and equipment, and a squeal of leather. The sound hung in the air long past the moment when it seemed that surely the vanguard would appear about the bend.

At last, the vanguard’s banners appeared, colours of royalty, of Lenayin, and of each of the eleven Lenay provinces. There was a Verenthane star, too, mounted on a pole. Sasha frowned, and thought dark thoughts. The vanguard soldiers were of the provincial companies, Lenayin’s most well equipped soldiers, riding tall on fine horses. Unusually, she saw they all carried shields. Some things, it seemed, were changing.

Behind the vanguard rode a contingent of Royal Guard, resplendent in red and gold. The nobility followed, many wearing fine, unfamiliar cloaks over Lenay armour and leathers. The outrider who had waited back now singled out one man from the group, riding alongside while pointing ahead. As the vanguard passed, that man came off the road and stopped before Sasha, several Royal Guards and lords at his back.

The lead rider came before them all, upon a great, roan warhorse. Broad, powerful, and oh-so-familiar. “Do you await anyone in particular?” asked her brother Prince Koenyg with amusement. The lords behind him laughed.

“I don’t know,” Sasha replied. “Are you anyone in particular?”

Koenyg frowned, and opened his mouth to retort. Then paused. And stared. “Is it…?” He edged his warhorse forward several more steps, peering closely.

“Easy Your Highness!” called one of the Royal Guardsmen. “It could be assassins!”

“Sasha?” Koenyg whispered. “Is that Sasha?” Slowly, achingly, Sasha slid off her rock, and pulled back her hood. And looked up at her brother.

Koenyg swung down from his saddle in such a hurry that Sasha’s hand twitched toward the blade within her cloak. But Koenyg made no move for his weapon, strode forward and embraced her. The pain of it nearly made her scream. Koenyg seemed to realise something was wrong, and released her.

Читать дальше