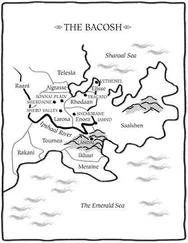

Then, as they found a narrow trail between fields, they passed a small village tucked between a narrow strip of trees and a lake. There were no pretty stone walls and painted window shutters here. This village huddled close, with mud walls and thatched roofs, surrounded by small animal enclosures. Beneath a full moon on a warm late spring night, all seemed well enough. But Sasha wondered at the winters, when the ground turned to mud and those narrow walls struggled to hold the chill winds at bay. About the village, lands lay unused, perfect for villagers to expand their animal pens or plant a new patch of greens. Sasha knew very well what fate awaited them should they try.

Soon, a castle came into view. There was a village nearby, and sheep in the fields beside the road. Even from this distance, Sasha could see banners hanging above the main gate. It seemed somehow sinister, a hulking stone block upon the Larosan fields. Years of warfare in Lenayin had led to some walled cities, yet castles remained unknown. Now, more strongly than at any time since she’d left Lenayin eight months ago, Sasha truly felt that she had arrived in a strange and alien land.

Kessligh and Rhillian walked down a moonlit street in the heart of wealthy, feudalist Tracato. Five more Nasi-Keth walked with them, but it was little more than show. If the feudalists wanted them dead, so it would be. They walked at the heels of a pair of armed city men, and took some relief in the night’s normality. From the nearby docks came the clanging of a bell.

“Thank you for not sending pursuit after Sasha,” Kessligh said to Rhillian.

“She was too long gone when I found out,” Rhillian replied. “I could not have caught her.” There was no accusation in her tone.

“Thank you all the same.”

“I am unhappy about it,” Rhillian continued. “She is only one blade, but she has skills in generalship, and a following amongst some of the Goeren-yai. If she rallies them, Lenayin could grow stronger.”

“There was nothing I could do,” Kessligh said quietly. Rhillian flicked him a sideways stare that suggested she disagreed. “I have never seen her like this.”

“I saw her,” said Rhillian. “She suffered.”

“It’s not just the pain.” The harbour came into view, down the road between rows of buildings. “She doubts.”

“You fear you have lost her. You brought her here to see your vaunted Nasi-Keth, and the grand future of humanity that you promised. Neither has made a good impression. Her foundation is gone, her hope for the cause, her belief in you. She runs to her people because they are her last remaining foundation. Save for Errollyn.” That last with an unpleasant, dry irony.

“She leaves Errollyn because she won’t force him to fight his own people,” Kessligh replied, edgily. “He would have followed her. He follows her too much, she knows that. She will find it difficult enough herself, to fight on that side, she would not inflict it upon Errollyn.”

“Human emotion is a fickle thing. Humans change on a whim.”

“Serrin too,” said Kessligh. “You used to be a nice girl.”

“Petrodor changed that,” Rhillian said bitterly. “You did not mind your tongue on my failings there. Now you play precious.”

The guiding pair of cityfolk turned down a dark, narrow lane. Soon they came to a nondescript door, and knocked a rhythm on the wood. A panel slid back, a password was given, and the door creaked open. The corridor beyond was narrow and gloomy, leading to a ramshackle courtyard beneath an open sky. Beyond the courtyard, a wide door led to a kitchen, grain and flour scattered about, signs of breadmaking, trails leading to a clay oven in the courtyard.

Two more city men awaited in the kitchen, blades drawn. Kessligh judged from their posture that they were ex-Steel, probably officers. A further door opened, and a small figure was ushered into the kitchen. There came barely enough moonlight through the windows for Kessligh to see his plain city clothes and longish hair about a slim, fine-featured face. The boy came forward on his own, to stand between the two big guards. Kessligh’s five Nasi-Keth remained in the courtyard, all armed, as were he and Rhillian. It would not matter. Rhillian’s upward glances told him that her serrin eyes had found archers in the courtyard windows. Crossbowmen, no doubt, and numerous. The corridors were too narrow for great swordplay, swinging the advantage back in the favour of Steel-trained men with no need for flourishing strokes. This was a death trap, should their invitees wish it to be.

“You came,” observed the boy Alfriedo Renine. His high voice was calm. Regal, Kessligh thought. Though not in a manner anyone familiar with the Lenay royal family might recognise.

“Alfriedo,” said Rhillian, and made a faint bow. “You seem well. I am pleased.” Kessligh stood with both hands on his staff. The boy seemed to frown, as though displeased that he did not bow as well.

Behind Alfriedo, one of several shadows scoffed loudly. “Be silent, Aleis,” said Alfriedo. And to Rhillian, “I do believe you, Lady Rhillian. I was not mistreated at the Mahl’rhen, quite the contrary. I was unhappy that some of your serrin comrades were killed in my rescue. I would have preferred a negotiated settlement. You have my condolences.”

Again, Rhillian inclined her head. “I accept them. In truth, my comrades were sloppy. Serrin are not known for great defence. We do not build in high walls, as we do not think in straight lines. It is offence to which our minds are most adapted.”

“You do not make threats here!” said the shadow by the kitchen bench behind. Kessligh strained his eyes, but could not make out the face. No doubt Rhillian could observe every feature. “You come because the power swings our way, and you have no choice, you do not make threats!”

“Aleis!” said Alfriedo in annoyance, turning fully about. “Am I the child, or are you? Hold your tongue like a man.” Kessligh was impressed. Alfriedo turned back to Rhillian. “Again, my apologies. Much has occurred, and many tempers raised.”

“I was not making a threat,” Rhillian said calmly. “Merely an observation. The time for threats has passed. I come to talk peace, for the sake of Rhodaan, in the light of the most terrible threat Rhodaan has yet faced.”

“You have finished your collaboration with the Civid Sein?”

“There was no collaboration,” said Rhillian. “They are opportunists. When your mother’s actions forced me to act and suspend the Council, the Civid Sein took the chance to flex their arm.”

“And my mother is dead because of it,” said Alfriedo. For the first time, his voice betrayed emotion.

“A great many people are dead,” Rhillian replied. “A majority of them Civid Sein. If my actions against the Civid Sein at the Justiciary are not sufficient proof that I do not side with their kind, I do not know what is.”

“Son,” Kessligh said tiredly, leaning on his staff, “you must understand the serrin motivation. Serrin do not act on spite. Rhillian was amongst the first to discover your mother’s death, and was sad about it. She sought to maintain an equilibrium. A balance, to the powers of Tracato. She saw your mother’s faction grow too strong, which in turn caused a backlash from the rural folk, most notably in the form of the Civid Sein-”

“You blame us for their rise?” Alfriedo interrupted, his high voice quavering.

“I’m a military strategist, primarily,” said Kessligh. “To every act on the battlefield, there is a response. As general, I am responsible for my enemy’s actions too, for everything I do, my opponent will counter. A clever general can use this to manipulate his enemy. Do you wish to be a clever general, Alfriedo? Or merely a boy protesting that his opponent did not play by the rules?”

Читать дальше