“In Valhanan, they say that of the town baker,” Sofy replied. Guardsmen laughed. Sofy was very pleased. It wasn’t often she’d think of a bawdy joke to make Lenay warriors laugh.

“I tell the owl and the baker to go away,” said Yasmyn, also laughing. “I want no child tonight.”

“Excuse me, if you please…” Willem interrupted in Torovan-they’d been speaking Lenay, of course, forgetting that one in their midst spoke none. “This is the spirit sign, yes?” He imitated Yasmyn’s sign, poorly.

“It is,” said Sofy, resuming the climb.

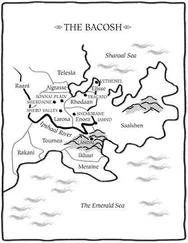

“Bad for Bacosh man make spirit sign,” Yasmyn added brokenly in Torovan. “Lenay man make spirit sign, good. Bacosh man make spirit sign, cock drop off.” Sofy giggled.

“Please forgive me,” Willem continued, “but I was under the impression that there were no Goeren-yai nobility in Lenayin.”

“Well yes,” said Sofy. “But Yasmyn is from Isfayen, in the western mountains. The faith is practised differently there. Even Isfayen Verenthanes still believe in spirits.”

“But…these are not the true gods,” said Willem, uncertainly. “How is it possible that one can believe in both?”

“Gods is gods,” Yasmyn said shortly. “Spirits is spirits. Different thing, yes? No problem.”

“The scripture says that it is blasphemy to worship any other gods besides the true gods,” Willem said firmly.

“They don’t worship spirits in temple,” Sofy said impatiently, trotting briskly up a flight of wet stone steps. “They’re just folk tales, really.”

“More,” Yasmyn disagreed. “Spirits are the world. Gods are the reason.”

“But…” Willem looked completely baffled now. “Surely the Archbishop of Lenayin does not consider such beliefs to be truly Verenthane?”

“It would take a very brave man, Master Willem,” Sofy said with no little sarcasm, “to tell the Verenthanes of Isfayen that their beliefs are not true.”

“But…” Willem protested once more.

From the front, Captain Tyrel finally lost his patience. “What’s the Archbishop going to do, man?” he said sharply. “Excommunicate the western provinces? Demand they convert properly? Some Baen-Tar priests tried once, their body parts were sent back packed in little baskets. Half of the army you’ve invited into your precious Bacosh doesn’t follow your gods at all. Best you get used to it.”

Willem coughed, and thought better of reply. Bacosh nobility were not accustomed to rebukes from their lessers. In Lenayin, he was perhaps learning, a man might rebuke whomever he chose…if he had confidence enough in his swordplay to survive the honour duel that followed.

It was a fair climb to the hill’s crown, but not greatly taxing-her days filled with riding and walking, Sofy had not been so fit in her life, and was rather enjoying the sensation. Another of those things Sasha had once assured her of, that she’d only now begun to appreciate.

The path made a switchback up the hillside, and then emerged on a small, wet courtyard that looked out over the little river beside which the Army of Lenayin had camped. Sofy could see a line of campfires, smothered in smoke and drifting rain, like a long line of flickering stars. Above was an old stone temple, with a bronze bell prominent between twin spires. Behind, a village of low, stone houses loomed dark in the rain, lit only by the glow from several windows. The temple might have been attractive were it not for the four long, iron cages suspended to one side of the courtyard from the branch of a huge, squat oak. Sofy had not seen such contraptions before, but she’d heard them described. Captain Tyrel, too, was darkly intrigued, and walked forward, raising his lantern. Each suspended cage was human shaped, and as the lantern light caught them, it became clear that each also contained a person.

“Dear gods,” Sofy murmured in horror.

“Devil’s fruit, they are called,” explained Willem, quite unperturbed. “Do men not use them in Lenayin? They are quite common in Algrasse, for punishing blasphemers and the like. Not so much in Larosa though, the Larosans are quite inventive.”

Two of the captives in the devil’s fruit were female, a woman and a girl, dresses torn and filthy. One was an old man with a thick beard. The fourth was a child of perhaps ten, half naked and long haired-whether male or female, it was impossible to tell. They slumped against their confining bars yet could not lie down, knees buckled against the front, heads back, as though desperate for rest. Perhaps they drank the rain. Cutting through the pleasant smell of damp forest, earth and woodsmoke, Sofy smelled human filth.

“How long have they been up there, do you think?” she asked.

“Oh, over a rainy period like this one, it can take more than a week to die,” said Willem, offhandedly. “Sometimes two. But come, Your Highness, since we are here, I shall explain to you the significance of this temple.”

“This is no way to kill a man,” Yasmyn said in Lenay. “There is honour in spilling blood. I see no blood here.”

“What did she say?” Willem asked, with mild curiosity.

“She wonders why lowlanders call us barbarians,” Sofy said coldly, striding to Captain Tyrel’s side.

“Highness,” said Tyrel, “these two are dead.” Pointing to the old man and the woman. Sure enough, Sofy saw their limbs and fingers were stiff. “The girl still lives. I cannot say about the child.”

What possible reason could anyone have for doing this to a child, Sofy wondered. Children had sometimes died in Lenay wars but, as Yasmyn said, those were deaths in hot blood, fuelled by ancient regional hatreds and motivated by the urge to destroy a blood enemy’s line. Those killings, however horrible, were quick. This was planned and calculating. Whoever had done this wished these four to suffer.

And why in the world was she still standing around wondering what to do about it? Jaryd never would have. Jaryd would have cut them down in a flash.

“Captain, take them down.”

“Aye, Highness,” said Tyrel, and his men moved quickly. None of the guardsmen seemed interested in disputing the order.

“Your Highness,” said Willem, “I’m really not so sure that’s wise…” Sofy ignored him, staring up at the girl Tyrel had insisted was alive. She looked lifeless to Sofy, but the captain was surely more practised in telling life from death than she. “Highness, these are clearly people guilty of some evil crime; the local people have every right to enforce their own justice in any way they-”

“They can argue with me once I’m queen,” Sofy said coldly. “And just pray that I’ll be as merciful.”

The girl’s cage came down with a clang, then the child’s. The clamps that held both halves together were released, and guardsmen carefully lowered girl and child to the pavings. Each stank, and were limp, scrawny and filthy. The girl had a rope tied about her neck and between her teeth as a gag. Sofy guessed the townsfolk did not wish to listen to her sobbing while they prayed. She wondered how many days a person could sob for, fearing all the time, while thirsting, hungering and cramping, unable to so much as scratch an itch.

Guardsmen tried to pour each some water from their flasks. The child did not respond. “There is a pulse,” Corporal Heyar said, feeling at the child’s slim neck, listening close for a breath. “Very faint. Unsteady. This one will die unless we get some food into the child.”

The girl gasped. Captain Tyrel patted her face, and sunken eyes fluttered open, beneath a fringe of straggly brown hair. “You’re safe, child,” said Tyrel, in Torovan. “Have some water.” The girl sipped, desperately. And coughed.

Читать дальше