The rain on the great tent grew heavier, a muffled rush that forced men to raise their voices. The local lords had provided the food, as it was understood by all that the Army of Lenayin was travelling light, and relied on allies for provisions along the way.

King Torvaal sat at the table’s end and made sombre conversation with Lord Elen, who was senior of those present, by some measure Sofy had not ascertained-wealth and lands, most likely. Sofy watched her father, and wished he would give her some kind of sign. Surely it affected him, one way or the other. He was leading his kingdom’s army to war. Surely he worried, or wondered at events to come. But, as always, there was nothing…merely a stern, impassive gaze from a lean and bearded face.

Koenyg talked loudest, a broad, commanding presence at the king’s right hand. It was all warfare, of course-horses and provisions and preferred formations of infantry. He’d learned a new word, “chivalry,” and seemed fascinated by it. Sofy knew that several of her handmaidens were similarly intrigued, although for very different reasons.

Damon sat opposite Sofy, and seemed more interested in her questions regarding the food than Koenyg’s regarding battles. Further down sat Myklas, with several younger lordlings. Of her three brothers, Sofy reckoned that Myklas was the one most enjoying this ride to war. In Baen-Tar, Myklas had found little interest in almost anything, rarely worked hard, and breezed through lessons on raw talent and intellect. Only tournaments had interested him. But lately, he’d seemed positively alive, gazing about at every new sight, and asking Koenyg questions of strategy, politics and logistics. He had even sought out his two-years-older sister on occasion, to ask her opinion of the towns they rode through, or on the artfulness of a temple spire, or the manner of the local townsfolk toward them. Sofy was pleased that her little brother had finally begun to take an interest in the world. She was only sad that it took a war to do it.

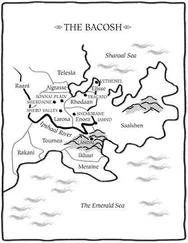

With the last meal finished, there came the stupid Bacosh tradition of excusing the women so that the men could talk on important matters. It was not a Lenay tradition at all, yet Koenyg and father insisted that while the Lenays were guests in the lowlands, they would obey some local customs as well. The entire table rose as Sofy excused herself, many of the Algrasse lords bowing to their future queen. A year ago, Sofy might have found it all very romantic and exciting. Now, it only depressed her.

She fetched Yasmyn from the secondary tables, and headed for the tent flap. Servants scurried, producing Sofy’s and Yasmyn’s cloaks, one darting into the rain to alert the Royal Guards.

“Was the food good?” Yasmyn asked her princess.

“Yes,” said Sofy. Armour rattled as Royal Guards came running in the rain. “I don’t wish to go back to the tent.”

“We could walk the line once more,” Yasmyn said with a sly grin. She enjoyed walking through the soldiers’ camps with Sofy. With the princess, men were never less than proper, but a daughter of Isfayen nobility could be expected to flirt a little.

“Perhaps,” said Sofy. “Lord Pelury says there’s a lovely old temple atop the hill on the other side of the stream. It dates to Saint Telvierre’s time; some say it was even constructed by Telvierre himself, sometime after the War of Three Rivers. All of the local nobility are baptised there, and they say it has many holy artefacts.”

“I’m not very interested in temples,” said Yasmyn.

“You could stay here.”

There was little chance of that, though.

Sofy and Yasmyn walked with their guard toward the stream beside the camp. There was light enough to see by, as many campfires burned beyond the tents, soldiers having foraged plenty of wood in anticipation of a cold, wet night. They made great blazes now, too hot for rain alone to extinguish. The air was thick with smoke and conversation, and even some laughter and song.

At the camp’s perimeter, several of the guards lit oil lamps, and walked to the fore. The stream sides were walled here, and a small stone bridge made an arc directly opposite. Crossing the stream, Sofy looked back down the road they had come. The army did not waste time contracting into fortified camps every night, soldiers merely camped and slept where they stopped. They were in friendly lands now, and no doubt the locals felt themselves in far greater danger from the army than vice versa.

“Your Highness!” came a call from behind. A cloaked man was running through rain toward them.

“Oh no,” Yasmyn sighed. “I thought we’d lost him.”

Sofy smiled. “Master Willem,” she said pleasantly as the tall man came to a panting halt and bowed. “I swear you must have the eyes of a hawk and the nose of a hunting dog. I had thought to leave your writings undisturbed.”

“Oh, but Your Highness, you must not trouble yourself for me! I am at your service for the duration of this journey! Where are you off to this evening?”

Master Willem was a scholar from a noble family of Algrassian scholars. The column had acquired him in the Algrasse capital of Tathilde seven days ago, when his services had been offered by his father, a noted scholar of Bacosh history. Since then he’d spent much time observing the Lenay Army, asking questions and writing in his carriage or tent.

“I had thought to take a brief walk to the Heronen Temple,” said Sofy. “I’m assured it’s not a long climb.”

“But…but, Your Highness,” Willem protested, “is it wise for the future Princess of the Bacosh to stray from camp with a mere eight guards?”

Captain Tyrel might have frowned at that. “I had not thought the lands of Algrasse so lawless,” Sofy said innocently.

“Lawless? No, no, Your Highness…not lawless. But such an importance as yourself should surely not…”

“I’m tired of being an importance,” Sofy declared, and resumed her walk. Her guards followed, and Yasmyn gave Willem a smug look as she whirled to Sofy’s side. “If I’m to become princess of this land, I feel I should come to know its places and people, do you not think, Master Willem?”

“Oh, a fine, worthy sentiment, Your Highness.” The tall man hurried to keep up. His earnest face was youngish-perhaps thirty-five, Sofy thought. Yet his jaw seemed to recede into his shapeless neck, and his posture was slightly hunched, in a way that was not fitting for a man his age. “Wobbly men,” Yasmyn had declared most Algrassian men, disdainfully.

Sofy walked briskly up the muddy trail toward where a path began to climb the opposing hill. Clear of the smoke and fires of the camp, the hill was more visible now, a dark and looming forest with a light burning on top. That, Sofy supposed, would be the Heronen Temple.

The guards’ lanterns lit gnarled, wet tree trunks and spreading canopy from below, to ghostly effect as shadows crawled and twisted through the wood. An owl hooted, and Yasmyn made the spirit sign to her forehead.

“Don’t be silly,” Sofy told her. “I think it’s a perfectly nice little forest, there’s nothing haunting here.”

“Eastern Verenthanes are crazy,” Yasmyn retorted. “Everywhere is haunted. You just can’t feel it.”

“There he is M’Lady,” said the guard directly ahead, holding up his lantern and pointing downslope to the left. Two bright eyes caught the lamplight, glowing like yellow coals.

“ Narl yl amystrash ,” Yasmyn called to the owl, in her native Telochi, making the spirit sign once more. The owl fluttered away on silent wings. Yasmyn grinned. “He heard me.”

“What did you say to him?” Sofy asked.

“The owl spirit, he foretells the future,” Yasmyn said. “In Isfayen, we say that the owl comes in the night to make a woman with child.”

Читать дальше