She was finding their enthusiasm infectious. All through the Tol’rhen, there was a love of learning, whether the martial arts, or languages, or the many disciplines that Sasha could barely get her head around. She was disappointed that, as in Petrodor, there were so few women interested in the svaalverd, but pleased that the lads all treated her as one of their own. Of the hundred or so students in the courtyard this early morning, Sasha could only count three young women.

Walking back to the main building, Reynold Hein joined her and put his arm about her shoulders. Sasha did not mind-it was nothing that the young men would not do with each other, in the spirit of comradeship. Reynold was simply indicating that he considered her one of the lads.

“Sasha, we have a Civid Sein meeting in the forecourt,” he said. “It would be grand if you could attend, maybe say a few words.”

“I was going to go and see Errollyn at the Mahl’rhen,” Sasha said apologetically. Not that she felt particularly apologetic, but it was a good excuse all the same.

Reynold just smiled. “Oh well, I don’t suppose even the Civid Sein can compete with Errollyn .”

Viewed from the courtyard, the Tol’rhen looked magnificent. It was the largest building Sasha had ever seen, as high as a grand temple, and far longer and wider. It had beautiful arching doors and windows, and columns that fanned out from the sides like an animal’s ribs. Its great dome towered above surrounding rooftops. Sasha had been told that it had taken nearly twenty years to build, even after the rest of the Tol’rhen had been completed, engaging the best human and serrin minds of the time.

Ulenshaal Sevarien cornered her at breakfast.

“Ah, Sashandra!” he boomed, as he heaved his wide, black-robed bulk onto the bench. “I hope you’re beating some manners into these little rascals!”

“Some of those bruises are mine,” Sasha admitted, indicating the young men. “I don’t know that bruises make for better manners though, it never worked on me.”

“A worthy experiment all the same!” Sevarien exclaimed.

“Ulenshaal Sevarien would administer beatings himself,” said Daish from Sasha’s side, “but the last time he broke a sweat was in the year 850.” The other boys laughed.

“Quiet boy!” Sevarien barked, but his eyes sparkled. Sevarien was as large as his voice, and had no discernible chin. He had been a butcher in his younger years, self-educated on books lent to him by a wealthy customer. That knowledge had impressed a visiting Tol’rhen recruiter enough to gain him a place as a student, from where he had risen to become one of the institution’s most accomplished scholars.

“Dear girl,” said Sevarien now, past a mouthful of porridge. “You have been here nearly a week. What do you think?”

“Of the Tol’rhen? It’s amazing.”

“Well, obviously,” said Sevarien, impatiently. “Do you think it could be replicated in your homeland?”

Sasha blinked at him. That was quite a thought. “Who would pay for it?”

Sevarien waved his hand. “Details, girl! No one shall pay for it if they are first not sold on the idea! Could it be done?”

Sasha chewed a mouthful, thinking it over. “I think only as a part of a noble education in Baen-Tar.”

“Why?”

“Because the provincial lords all think the Nasi-Keth teach blasphemy. The poor folk aren’t interested in any education that won’t make them extra coin; you’d do better teaching them to improve irrigation or cropping than philosophy or languages…”

“Bah.” Sevarien waved his hand again. “We had the same issue here. The poor stopped their nonsense when they realised what higher status they could attain with a Tol’rhen education.”

Sasha smiled. “There is no higher status in Lenayin,” she said. “If you’re poor, you work with your hands and attain status with hard work and skill with a blade. The only men of letters and law are nobles, and nobility is a matter of birthright, not education.”

“A travesty!” proclaimed Sevarien. “One of the greatest travesties that continues today across Rhodia. If there is one institution that we should all bend our backs to see destroyed, it is nobility. Fancy declaring that any of these lads, however bright and hard working, cannot rise to the same level as some soft-handed lackwit, simply because he had the good fortune to be born into a blue-blooded family.”

“I agree.”

“You know,” said Sevarien, jabbing a spoon at her, “you should attend a Civid Sein gathering.” Sasha repressed a sigh. “Being of noble birth yourself…or no, not noble. Royal! And yet you dress without fancy, and sport calluses on your hands, and ask no favour for the fortune of your birth. You rejected such favour, indeed!”

“She has to go and see Errollyn today,” Daish explained.

“Tomorrow then!” Sevarien declared. “More of the movement enter the city every day; it would be quite something to have someone who has rejected royal heritage address them! Quite something indeed!”

“You don’t really want to have much to do with the Civid Sein, do you?” Daish observed as they walked a paved hallway after breakfast.

“I didn’t reject royal heritage for the reasons they suppose,” Sasha told him.

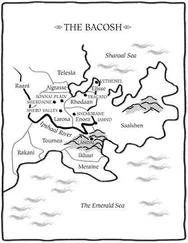

It was all a big debate, here in Tracato. Two centuries ago, the serrin had innocently supposed that human society might work better on merit. In Enora their vision had worked well, because Enora had slaughtered all its nobility. In Rhodaan, nobility survived, and now regrouped. The Civid Sein were the anti-nobility, formed largely of poor people and farmers, though not entirely. It had a strong leadership core here in the Tol’rhen, and with fears that the Tracatan nobility would rather negotiate with Rhodaan’s feudal enemies than fight, more and more were moving to the city each day. To keep the lords nervous, it seemed.

When she reached the great classroom, it was full to overflowing. All chairs taken, Sasha joined the crowd standing along the walls, and found a place near the front of the chamber, where Kessligh sat with three Ulenshaals, and recounted the history of the Great War. The Rhodaanis knew it only as “The Cherrovan-Lenay War of 827,” which to Sasha’s ear seemed insultingly minor for so grand a conflict.

Kessligh had been telling this history the last two days, having finished his previous lectures on the nature of Lenay society and feudal power. Those had been opinions, but these were events, experienced by Kessligh himself as a young man. The Ulenshaals, and most of the Tol’rhen students, were intrigued to have the man who had made much of that history in their midst, having paid far too little attention, they admitted, to the study of Lenay and other highland histories.

It fascinated Sasha to listen to Kessligh speak. She had heard these stories many times, but in her youthful impatience, she’d always neglected to ask about the details, wanting instead to hear the grand conclusion. Now the Ulenshaals interrupted continuously, probing on this or that point of strategy, or the actions of minor players. Kessligh spoke incisively, without the troubled frown that Sasha recalled from her own discussions with him. Perhaps he found this audience more receptive. Sasha heard details of that time that astonished her-things Kessligh had done, relationships with other warriors that she’d not suspected, incidents of humour she’d never heard. As she listened, she marvelled at her own stupidity, that she’d had such a treasure beneath her own roof for so long, yet had taken it so completely for granted.

The thoroughness of the Tol’rhen’s love of knowledge astonished and delighted her. Knowledge in Lenayin meant stories, told over an ale after a good meal, or crafts passed through families for generations. Here, knowledge was precious, to be treasured, stored and shared around. And to be given across classes, to poor and rich alike, and across races. Such a place could change the world, Sasha realised. And Ulenshaal Sevarien had asked her if such an institution could be replicated in Lenayin. Not a bad idea at all, she reckoned, and began thinking on it more seriously.

Читать дальше