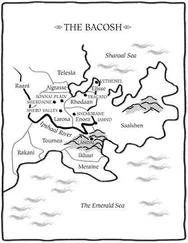

The King had not demanded more than twenty men in every hundred capable of fighting, through all of Lenayin. Much discussion about campfires now speculated as to the size of the Lenayin population in total…thirty thousand marching soldiers made one-fifth of a hundred and fifty thousand fighting men. Which would be only half of the total number of Lenay men, when counting children and elders, making three hundred thousand men in Lenayin. Double that to account for the women, and there were six hundred thousand people in all Lenayin. It was a number so large, many refused to believe it. Scattered for countless centuries across their uncounted rugged valleys, so many people had divided into equally countless tribes, with differing tongues, beliefs and ceremonies. Now, thinking of just how many people Lenayin actually had, Jaryd wondered if any other human land possessed the sheer scale of fractious diversity the gods had granted his homeland.

No wonder we’re always in such a mess, he pondered, gazing about at the long, settling column. There was no thought of fortified camps here on the Telesian plains. Telesia had few people, and had only escaped conquest by Bacosh neighbours because it possessed so little that anyone wanted. Mostly it made a bulwark between the Bacosh and southern Lenayin, and there was no threat to a Lenay army here.

Jaryd set his boots aside and rose barefoot. “Come,” he said to Andreyis. “We’ll spar while there’s still light.”

Andreyis looked tired too, but he removed his boots and rose all the same, withdrawing his practice stanch from within his bundled gear. They took stance on a clear patch of grass, shields laid aside, and practised in the traditional Lenay style-two hands, no shields and little mercy.

Some other men did the same, and most of those pairs were also made up of a youngster and a more experienced warrior. Jaryd now had twenty-two years, but he had once been heir to the province of Tyree, and perhaps the most celebrated sword- and horseman in that region. Since then, he had been deposed, his family dissolved by ancient clan law, his youngest brother murdered and his siblings married off. He had taken refuge in a Goeren-yai village, sought revenge, and found something perhaps greater than that which he had lost. He remained uncertain of exactly what it was that he had found. So many things, he was still discovering every day.

Sparring over, he and Andreyis returned to the campside, and took their places in the circle.

“You should train with those damn shields, lads,” Teriyan told them. “We’ll have to use them soon enough.”

“Foundation first,” said Jaryd. “Shields later. The lad has to walk before he can run.”

“I can walk fine,” Andreyis muttered, rubbing a bruised arm where Jaryd’s stanch had caught him. “I’ve been doing nothing but walking for weeks.”

“When I was a noble,” Jaryd said, lounging back on the grass, “my father once received a travelling entourage from Larosa. Some bunch of idiot lowlands nobility seeking trade, horses and powerful friends in Lenayin. Anyhow, this lord’s heir was seventeen; I was fifteen at the time. He was boasting to me about what a great swordsman he’d become, of how he’d trained with a master-at-arms from his father’s army since he had barely ten years, and how he thought himself more than a match for anyone in Lenayin.”

Men grinned or snorted. In Lenayin, boys held the stanch and learned footwork from the moment they could walk. “I challenged him to spar,” Jaryd continued, “and beat him black and blue from one side of the circle to the other. Then I handed off to my brother Wyndal, who’s another two years younger again, and not much of a fighter, but he did scarcely worse.”

“What’s your point?” Andreyis asked. The lad was a little touchy where his swordwork was concerned. Well, Jaryd supposed, it couldn’t have been easy having the stuffing smacked out of him all through childhood by Sashandra Lenayin. Now, fate had afflicted another great and cocky warrior upon him. Probably he was getting sick of it.

“My point is that everyone can improve. That little lowlands snot thought he was great, but he learned that greatness in the Bacosh and greatness in Lenayin are two different things. Perhaps somewhere out there is another kingdom of warriors who make Lenays look foolish with a blade. Always assume you’re not as good as you will be tomorrow, if you work at it.”

“Listen to the pup,” Teriyan remarked, “spouting wisdom like he knows what it means. You come and talk to me when you’ve seen even half the battles I’ve fought in, youngster.”

“Aye,” said Jaryd, smiling, “you’ve fought in so many battles that last time we sparred, I could hear your bones rattling.”

“Sparring is not warfare, boy.” Teriyan looked less than his usual good-humoured self at that reminder. “When the formations line up, and you see nothing but Rhodaani Steel from one end of the horizon to the other, then you’ll learn the value of experience.”

Jaryd just smiled, and stretched out on the grass. Andreyis joined him, stretching an arm above his shoulder.

“Am I better than that Larosan boy?” Andreyis asked sombrely.

“That little fool? No contest, you’d kill him one-handed.”

“I know I’ll never be great,” said Andreyis. “I’ve had some of the best training of any man my age in Lenayin, with Kessligh and Sasha, and now you. I should be better than I am.”

“Not true,” Jaryd insisted. “Kessligh and Sasha fight with svaalverd, you’ll not learn a thing from them. I think it might have hurt you, truthfully.” Andreyis looked doubtful, but did not argue. “Look, you’re a tall lad, you’ve not filled out properly yet. Your technique is fine, you just need to get quicker, and that’ll take care of itself as you get older.”

“I’ve heard it before,” Andreyis said quietly. He said nothing more, and lay on his back gazing at the sky.

Jaryd watched him. In truth, the boy had a point. His technique was quite good, and he did quite well in set, predictable taka-dans. But when forced to improvise it often broke down, and he simply wasn’t very quick. Jaryd had never considered what it might be like to be born without the skills he took for granted. Andreyis’s admission bothered him. In Lenayin, for a young man to admit to anyone, even his closest friends, that he did not think himself much of a swordsman, was akin to admitting himself a coward.

Andreyis was an unusual boy. He was clever, but seemed to have no particular skills at which he excelled. He was good with horses, thanks to a childhood working on Kessligh and Sasha’s ranch, but even there, his natural skill with the animals was not the same as that of his younger workmate Lynette, Teriyan’s daughter. Popularity in Baerlyn eluded him, despite (or perhaps because of) his friendship with Baerlyn’s two most famous residents. He had fought in Sasha’s rebellion, and gained manhood, but not the respect that came of a man making his own way, and standing on his own two feet.

When the Baen-Tar herald had called on Baerlyn in the winter, Andreyis had been amongst the first to put forth his name. His father ran a wagon and harness trade with an elder son, and the younger son was dispensable.

This young man expects to die, Jaryd thought, watching Andreyis now. He seemed to find it preferable to continuing to live the life he had. For the first time in his life, Jaryd found himself questioning the obvious truths that all young men of Lenayin had shared since they were old enough to understand such words as “honour,” and “manhood.” Andreyis would perhaps never be a great warrior, but he was a good young man all the same. Was goodness worth nothing to a man, if greatness could not accompany it?

Читать дальше