Sasha arrived at the circle as the priest gave incantations. Damon made room for her and Markan. He grasped her hand, and she squeezed back. Before them, Torvaal, the fourth King of Lenayin, lay on his back beneath a black cloak. The blackness of his beard only made his face seem shockingly pale. It did not seem real, that he could be dead. Several men had tears in their eyes. Sasha spied Myklas across from her, at the side of Great Lord Heryd of Hadryn, struggling to hold back sobs. Damon too seemed in difficulty. Sasha wished she could feel something. Anything at all.

It passed in a blur, the recitals, the removal of the Highland Ring from Torvaal’s finger and onto the finger of Koenyg. Then, finally, the crown-a thing much unseen in Lenayin, as the first king, Soros, had recognised that such an overt statement of superiority would arouse the displeasure of the proud lords of Lenayin. It was a simple band of metal, made from sword steel. The priest produced it from somewhere, and placed it on Koenyg’s head, and all about the circle knelt. Koenyg was grim and bloodspattered. From his posture, Sasha reckoned he bore a wound to his side, however he tried to hide it. It did not seem serious. He made perhaps the perfect image of a new Lenay king, battleworn and unsmiling, civilised yet frightening. The northern lords would be pleased to see Koenyg take full command. Most of the lords would. Yet nothing could hide the shame of an Army of Lenayin that had lost its king, then run away.

Looking around the circle, Sasha noted who was absent. Kumaryn of Valhanan. Arastyn of Tyree. Her nemesis, and Jaryd’s, both dead. She could not feel happy about it. Parabys of Neysh, too. Four of the eleven great lords fallen. Only the Isfayen had been fast enough in handing from father to son to attend these funeral rites. Some of the others, Sasha had heard, had left their sons in Lenayin to tend their estates. Temporary great lords would need to be found, for the purposes of command.

Rites complete, embraces were exchanged with the new king, siblings first. Then all stepped away while Royal Guardsmen came to take the king’s body, wrapped in its black cloak, onto a waiting cart. There would be no grieving over the corpse, not for Lenays in war. The great lords assembled behind Koenyg, who walked behind the cart, as it picked its way between the fallen. Sasha walked at Myklas’s side. For all his dried sweat and dirt, he seemed to have barely a scratch.

Men talked in low voices of the battle. Sasha risked a look at Great Lord Heryd, walking at Myklas’s other side. “I hear tales,” she said. “My little brother fought well, it seems.”

Heryd’s blue eyes were pale, nearly expressionless. “I have rarely seen such skill,” he said. “He was the best of us.”

Sasha blinked. Hatred between her and Heryd was mutual, yet she knew the Great Lord of Hadryn was no sycophant. Myklas said nothing, with eyes only for his father’s body on the tray of the cart ahead.

The cart continued beyond the battlefield, toward where the Army of Lenayin now camped, several hills beyond. The procession did not follow, abandoning that job to a gathering of lesser lords on horseback. Sasha turned back to where Isfayen were following behind with horses, and remounted.

She headed along the great swathe of fallen bodies toward where she figured the centre of the battle had been. Eventually she saw the stag-on-maroon flag of Valhanan, driven into the ground near some parties of men and carts. She left her horse with her two Isfayen guards, and walked to those attending the dead and wounded. Soon enough she found Byorn of the Baerlyn training hall, and embraced him hard. He seemed pale and shocked, his long hair matted with other people’s blood. Wordlessly, he escorted her past piled bodies and entangled, bloody limbs, until they reached the body of a large man with thick red hair, a fatal sword wound through his ribs.

Teriyan.

Sasha collapsed in tears, and sobbed onto his shoulder, as Byorn knelt with a hand on her back. This was how she should have grieved for her father, had her father permitted such a thing. But this man had been far more a father to her than her real father had. And he was the true father to one of her best friends.

“How am I going to tell Lynette?” she asked Byorn, helplessly between sobs. “Who’s going to tell poor Lynie?” And Byorn, from whom Sasha had never seen emotion in her life, struggled to hold back tears.

“I can’t find Andreyis,” he said in a low voice. “I’ll keep looking, I swear to you. But he’s not amongst the living or the dead.”

For the rest of the day, Sasha could not speak.

It was without question the strangest day of Sofy’s life. She sat at camp and attempted to keep herself occupied with mundane tasks, while beyond the next rise upon the Sonnai Plain, a hundred thousand men and more fought to the death. The wind was from the west, the wrong direction to assist the sound in carrying, yet the din assailed her ears all the same, rising like some unhappy spectre, with wails and cries to chill her bones.

The matrons of the Merciful Sisters insisted on prayer, and so Sofy, her maids, and the other ladies of the camp knelt in the communion tent and recited verse after the men had gone. Then had come needlework, and Sofy attended to some of Balthaar’s clothes in the manner of any good wife, gathered with the other ladies in the royal tent. Some had attempted gossip, forced and nervous, against the smothering din of war that lay over the camp. Several of the ladies, Sofy knew, feared for their position in Sherdaine should their husbands fall on the field. Most had returned to family castles, but a few had accompanied their husbands in camp with servants, and now readied to make a fast escape should news from the battle turn bad.

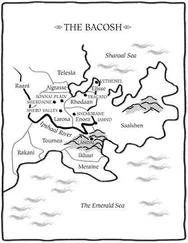

Sofy wondered what the ladies truly feared the most-the defeat of the united Bacosh Army, or the shudder that such a calamity would surely send through their land. Many lords killed, lines of succession called into question, challenges from rivals, siblings, cousins or power-hungry neighbours, and a great rearrangement of feudal boundaries that might last for several years beyond the great defeat. She wondered if such a defeat might teach them, finally, the futility of attacking the Saalshen Bacosh. Such attacks had grown fewer and fewer in recent decades, and consisted mostly of boastful dukes and other, ambitious lordlings hoping to make a name for themselves by demonstrating their courage, and trying to take the Steel unawares. Some had succeeded, in surprise at least, and had penetrated small armies some short distance into Rhodaani or Enoran lands before beating a hasty retreat in the face of advancing Steel forces. Such daring men had gained great reward of prestige for their “successes,” thus tempting others to copy their methods. The Steel rarely gathered in full force, as its soldiers rotated back to their families, and others to training, leaving only smaller groups to guard the border. But most often, even such smaller formations had dealt these incursions a crushing blow.

Sofy had now come to suspect that some lords in this great army were happy to see the war not for religious or moral reasons, but simply for the opportunity it presented to grab available lands or claim titles, once so many of those previously in possession had been slain. “The great dice,” she’d heard men call it. The great gamble of throwing so many men into battle, and hoping that it was one’s rivals who would fall, and not oneself.

Occasionally a messenger would arrive and inform them of the battle’s progress. Such messengers never spoke in much detail, and Sofy was uncertain whether that was because they did not expect a group of women to understand, or because they simply didn’t know. But she knew the battle was progressing better for the Bacosh because by noon the fighting was still continuing. Both victory and defeat seemed equally precarious outcomes for her personally, and for those she loved. She did not know when the Army of Lenayin would fight its first battle to the south, or how long the word of its outcome would take to reach them. She merely concentrated on her needlework, one stitch at a time, as though by the correct placement of thread and steel, she could stitch all the fates into some more agreeable arrangement.

Читать дальше