Sasha turned her horse about, and rode with her Isfayen back toward the right flank. If the centre held, only for the flank to fold because she were distracted elsewhere, she would sacrifice everything for which her father risked and fought. She rode on, as fire erupted behind, and did not look back.

Andreyis awoke. He heard cheering, hysterical laughter, the celebrations of victorious warriors. “We’ve won,” he thought dreamily. Then he realised that he could not recognise any words the men spoke.

He lay on his back on the green grass of a Larosan field. His right arm hurt worse than anything he could remember, but at least it was still attached to his body. His head ached and when he put his left hand to his temple, it came away bloody. He recalled the horse bearing down on him, and realised it must have hit him. Better that than the serrin rider’s sword.

Thud, came more, nearby sounds. Thuds, and a whistling, fast fading. Another sound, a sharp crack, then a tortured, creaking rush, as a heavy mechanism of ropes and gears unwound. That would be a catapult firing. It sounded close.

He half-rolled, and managed to look up. Sure enough, the Tracatan artillery was near, cart-mounted ballistas drawn by oxen, and a pair of enormous catapults, each behind four pairs of oxen, intricate and frightening to behold at this range. Men swarmed over them, perhaps a dozen to each, carefully lifting ammunition from the trailing cart as others, shirtless and powerful, wound fast at complex gears, creaking the huge throwing arms back into place with remarkable speed. An ammunition shot was loaded into the arm’s enormous “palm,” a flint struck, and suddenly the shot was aflame…yet it was strangely coloured-blue, and barely visible. Then, crack, as the release was pulled, and the arm uncoiled once more, hurling a flaming missile across the cloud-strewn sky.

Still the cheering. Andreyis sat up, his arm cradled as it screamed with pain, yet he did not cry out. He stared instead at the backs of the Enoran infantry, perhaps a hundred paces before their artillery. They were cheering, not fighting, swords waving in the air. Many leaned on their shields, utterly spent. Others dropped back to check on the fallen.

The fallen, Andreyis saw, were everywhere. There were frighteningly more Lenays than Enorans, on his patch of ground. They made a grisly carpet, still writhing and groaning in places, as though the dead themselves protested this fate.

Andreyis struggled to his feet. There was a rise of gentle hillside beyond, and up it, he could see men fleeing. Lenay men. The proudest warriors in all Rhodia, running for their lives as an Army of Lenayin had never run before. Into their midst fell a rain of ballista fire. Nearby, where catapult shots fell, there followed great eruptions of blue-tinged orange flame.

“Stop it!” Andreyis shouted at the nearest ballista crew. “Stop shooting!” Men turned to look at him. “Stop shooting, damn you! You’ve won! Let them go, have you no honour?”

They ignored him, shirtless, sweaty men winding fast, and placing more forearm length bolts in the empty breaches. More bolts sprang skyward. Andreyis found that he was crying. He looked about for a sword, but before he could bend his injured body to fetch one, hooves thundered close, and an Enoran cavalryman dismounted before him, weapon brandished.

“You, shut it,” the Enoran demanded in Torovan.

“Tell them to stop killing a defeated opponent!” Andreyis shouted back. “You have no honour!”

The Enoran advanced, and laid his blade against Andreyis’s throat. His eyes were battle-wide and deadly. “You serve evil,” he said coldly. “Your masters would kill us all. Enoran mercy was stolen from us long ago.”

Andreyis brought his good arm down hard across the Enoran’s wrist, kicked at his knee, and twisted expertly. The man fell, and found himself staring up at his own weapon, levelled at his throat. “I am friend to Sashandra Lenayin and Kessligh Cronenverdt,” Andreyis hissed, “and I at least have honour! If Enorans do not, I shall teach it to you!”

He turned and ran, as best he could, at the nearest ballista cart. Men saw, and shouted warning, but then another horse blocked his path, and Andreyis found himself staring up at the bright, golden eyes of a serrin. He stopped, trying to imagine a way around this obstacle that might do some good instead of just dying immediately. The serrin shouted something, and waved his sword.

More shouts answered, and artillery fire ceased. A silence hung in the air, as the cheering had faded. It hung like a great emptiness over the fields. The serrin looked down at Andreyis. “You ask much of me,” he said grimly. “It has been long since Saalshen or Enora has faced an honourable opponent in battle. And longer still since we have been pressed so hard as this. Many of your countrymen live to attack us once more. I would rather it otherwise.”

Andreyis held the sword up before his face in salute. He then laid it on the ground before him. “I am bested,” he declared. “My life is yours. I ask only that my honour remain unstained.”

The serrin stared at him for a long moment. “Says he’s a friend to Sashandra Lenayin and Kessligh Cronenverdt,” said the cavalryman, climbing to his feet. “That was a nifty trick. Could be true.”

“Are you?” asked the serrin.

To lie was dishonourable. Sometimes, amongst Goeren-yai, that mattered little. But upon a field of battle, surrounded by dead and dying, honour was all. “Yes,” said Andreyis.

The serrin nodded. “Take him to custody,” he said. “With their king dead, Sashandra Lenayin may figure prominently in the transition of power.”

“She may be dead too,” the cavalryman cautioned.

“I’ve a team of artillery on the left flank who might say otherwise, could the dead speak,” the serrin replied. “She was alive that late in the fight, we shall assume she lives until we discover otherwise.”

Andreyis stared across the masses of fallen Lenay warriors. The king was dead. The Army of Lenayin had broken and fled before their foe. Surely there had never been a blacker day to be a Lenay than today.

A Rathynal circle was already assembling upon the field of battle as Sasha approached. There were too many dead on the field for riders to reach the place where the king had fallen, so Sasha dismounted two hundred paces distant, and walked. The Great Lord Markan of Isfayen walked at her side-a young man, bigger even than his father Faras, with a proud gait and flowing black hair. Faras was dead, struck through the eye by a serrin arrow in the concluding actions of battle, as the cavalry flank had sought to hold back their opposition’s thrusts into the retreating Lenay infantry, and prevent the retreat from becoming a total rout.

There had been an Isfayen ceremony for Faras, after the Enorans had granted truce for both sides to collect their dead and wounded. It had been brief, in the way of bloodwarriors at war, yet it had required Sasha’s presence, as she was now adopted Isfayen, for the duration of this war. Thankfully the ceremony had required nothing of her save her presence, while a spirit talker had appealed to the spirits to take Faras amongst them, and return him to the earth and the sky, and the world of living creatures between. Sasha wondered where a Lenay spirit would go, so far from home. Would he stay here, to rebirth among foreign plants and animals? Or would he wander the long journey home, in homesick longing for the highland mountains and forests?

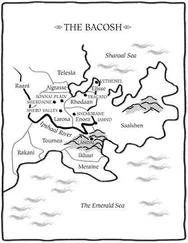

The walk to the Rathynal circle was carpeted with dead, men and horses alike. Most were Torovan. Scattered amongst them were Royal Guardsmen. Occasionally, an Enoran, though those were being fast removed from the field. Carts stood near, and Enoran men in light armour, hauling their dead into the tray. Serrin too, with leather bags of medicines, and tourniquets and bandages, searching for wounded who could still be saved. Enoran and Lenay men passed each other in silence-the Enorans wary, as the Lenays were still armed. The serrin, however, seemed less wary. Sasha knew that the Steel rarely granted such truces to Bacosh armies, and would usually hold the field until they had collected all their own dead and wounded, then abandon the defeated foe to their dead, if they dared return. But the Lenay king was dead, and Sasha suspected it was the serrin who had granted this small mercy.

Читать дальше