Adrian Tchaikovsky - Dragonfly Falling

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adrian Tchaikovsky - Dragonfly Falling» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dragonfly Falling

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dragonfly Falling: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dragonfly Falling»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dragonfly Falling — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dragonfly Falling», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I will never work for the Empire!’ Totho snapped, sitting halfway up, then falling back, his head still clamouring.

‘I have a case to make.’ Drephos sounded amused.

‘I know the Empire. I know how they look on other races, even if they aren’t halfbreeds!’ Totho said through his teeth.

‘And what if they are?’ There was such dry humour in the man’s voice that Totho propped himself up on one elbow to see what was so funny.

Drephos raised his hands, one cased in metal and one without, and slipped his cowl back. The face he revealed was mottled and blotchy with grey, and his eyes had no irises. There were many grades of halfbreed, Totho already knew. A few like Tynisa were just like one parent or the other, and some others managed to combine their heritage into something exotic and attractive. Most were like Totho himself, stamped with an intermingling of bloods that others saw, and then judged them by. Drephos, though, was of those few who seemed actively twisted by their inheritance. His features were lean and ascetic but subtly wrong in their proportions. Even when he smiled the effect was unpleasantly skewed.

‘I am aware, young man, that I will win no prizes for my beauty, but believe that I, therefore, judge no man on his face or blood,’ he said.

‘Drephos,’ Totho said softly. ‘And that other name, the long one. Moth-kinden names?’

‘My mother was left to name me. My father, unknown and unmourned, bestowed on her only so much of his time as it took to rape her. Wasp soldiers are not known for their benevolence towards prisoners or slaves. I suppose few soldiers are.’

‘But you said you were an artificer?’

The lopsided smile grew wider than seemed comfortable. ‘Remarkable, is it not? And yet something from my father’s seed has communicated to me all the workings of the world of metal, for here I am, so much of an artificer that they turn their hierarchy inside out to accommodate me. Without me the walls of Tark would still be whole, utterly unbreached. Yet my mother’s people sit in their caves and draw pictures on the wall, and pretend they are still great.’

Totho sank back into the chair. There was a feeling snagged deep inside him, because he was now interested. This maverick artificer, who seemed to have carved out some high station even amidst the Wasp Empire, had caught his imagination.

‘Was it your idea,’ Drephos asked softly, ‘to destroy my airships?’

And there was a leading question, and more what Totho had been expecting. It would be better, he thought, to return to familiar ground. ‘It was.’ He steeled himself.

‘Don’t be shy of it,’ Drephos said. ‘It was a well-planned raid. I’d guessed that the Ant-kinden hadn’t considered it. I have dealt with them before and there is not a grain of intuition in their entire race. But you saw the threat and acted, even as I myself saw our vulnerability. That is why I had two whole wings of soldiers on standby, to rush to the airships the very moment anything disturbed the camp. And just as well I did.’

So that was it: the final nail in the coffin for Totho’s desperate plan. He recalled in his mind a brief swirl of images, the fighting, the fury. A sudden lurch took him, and he tried to spring out of the chair. Even before the young woman had moved to restrain him, he was already toppling, the pain in his head making it impossible to stand. Her arms grappled his body, surprisingly strong, hauled him up and sat on him the edge of the chair.

‘Prisoners. ’ Totho muttered

‘Yes?’ Even with his eyes closed he could hear Drephos moving near.

‘You said you had taken prisoners. Other prisoners.’

‘Two to be precise, although one of them may not recover enough to be questioned.’

‘Was there.?’ He squinted up at the man. ‘Was there a Dragonfly-kinden man? He would have had-’

‘I know the Commonwealers, the Dragonflies,’ Drephos confirmed. ‘After all, the Twelve-Year War was the testing ground for some of my best inventions. I’m sorry, though, but the other prisoners are just Ant-kinden. If there was a Dragonfly last night, he has not been taken alive, nor did any escape, to our knowledge. I am afraid it seems most likely he is amongst the fallen.’

Eighteen

General Maxin took a last moment to understand his reports. They were a secret of his success, these reports. He had very able slaves whose sole task was to compile the wealth of information the Rekef Inlander brought, so he could then look through these few scrolls and read in them all he needed to know. Details could come later. Details he would ask for. For now he had his picture, his mental sketch of who was plotting, who was falling, who was on the rise or on the take.

And his information was not just fodder for the Emperor’s ears, either. Maxin had his own schemes. The Rekef was a young organization, created in the very closing years of the first Emperor’s reign by the man whose name the spies now bore. The structure and hierarchy had evolved over the next twenty years but at some levels it was still changing. Maxin had his own plans for it.

There were three generals of the Rekef, the idea being that each controlled his own particular section of the Empire, spoke to the others and reported to the Emperor. In practice, of course, those men who were ambitious enough to become generals in the Rekef did not suffer the interference of their peers.

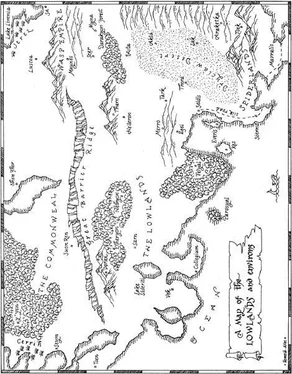

And Maxin himself was winning. That was all he cared about. He was the man who sat amongst the Emperor’s advisers. General Brugen was chasing shadows and savages around the East-Empire amidst famine and bureaucracy and the stubbornness of the slave races. General Reiner was wrestling with the Lowlands. For the moment, Maxin was winning and he intended to keep it that way.

Of course there had been setbacks. Brugen was a conscientious man with more small troubles than his staff could conveniently cope with, so Maxin did not fear him. General Reiner was another matter, however. Only recently a man whom Maxin had raised to the governorship of a city, a man well placed for Maxin’s plans, had been disposed of by Reiner. The city, its Rekef agents and its considerable wealth, had then been put in the hands of Reiner’s shadow, the execrable Colonel Latvoc.

It had been a challenge to Maxin’s primacy, of course, but Maxin enjoyed challenges — as long as he won in the end.

He would win in the end. He had the Emperor ready to love him like a brother. Or perhaps not like a brother. After all, Maxin had overseen the murder of all the Emperor’s siblings bar one, and dealt with several other rivals at the same time. Nevertheless he had now presented the Emperor with perhaps the one gift all his Empire could not give him. It would be leverage enough, Maxin decided, to call for a major restructuring in the Rekef, and then Reiner and Brugen would understand, however briefly, that any army could only have one general.

He rolled up the scrolls and stowed them in the hidden compartment of his desk, then left to meet the Emperor.

They had moved the slave to a better cell, one with tapestries and carpets, some Grasshopper carvings for ornament, and no natural light. Uctebri had complained at the brightness of the gaslamps, though, and now oil lanterns hung randomly from the ceiling about his chambers, making them look more squalid than ever.

Still, he came to greet them at the first call of his name and Maxin knew they had been feeding him well enough. This scrawny creature seemed to have a remarkable appetite: it was not clear precisely where so much blood could go .

When the prisoner had presented himself, Alvdan circled him cautiously. Maxin knew the difficulties here were ones of belief. What the wretched old Uctebri had proposed was impossible, quite impossible, as any rational mind well knew. The thing the old Mosquito promised, the golden, impossible dream of sorcerers and ancient kings, belonged in the forgotten folk tales of slaves. When Uctebri spoke of it, though, it was hard not to remember that his very race was supposed to be extinct, to be entirely mythical. While he rasped the words, with his quiet certainty, his strange insistence, it was possible for the rational mind to be tricked into believing, just for a moment, that the quackery was real.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dragonfly Falling»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dragonfly Falling» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dragonfly Falling» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.