The Bandit King

(Hedgewitch #2)

by Lilith Saintcrow

To Mel Sanders, because she knew I could do it

It is the Eighth Crossed Year of the Stag, or, more precisely, the Interregnum between the death of Henri di Tirecian-Trimestin (sixth of his name, thirty-one years reigned, and peace upon his shade) and the rise of the Bandit King (long may he reign, by the Blessed)…

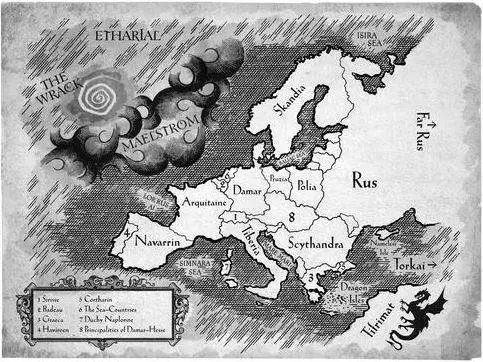

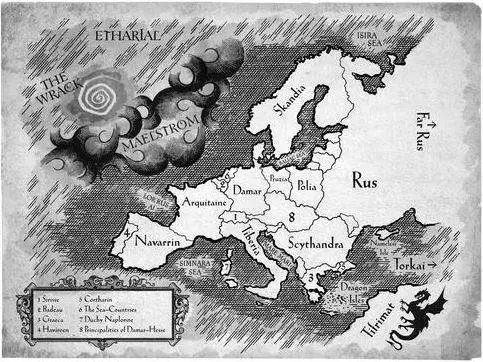

Timrothe d’Orlaans, the surviving brother of King Henri, has taken to the throne. Yet the Blood Plague stalks Arquitaine, and her borders are menaced as always by the Damarsene shadow. The new King’s touch does not cure the sickness, and the whispers from the far provinces are full of unrest.

A Queen, they say. A Queen who holds the Aryx, though the new King cannot have been crowned without it. Was he truly crowned? Is she merely a rumor, or is she flesh? What of the traitors who slew old King Henri VI and his daughter-Heir, the half-Damarsene Princesse who was to be our surety against Damar’s aggression?

A Queen, they say. A Hedgewitch Queen, the common people add, for hedgewitchery is their purview, and such a Queen likely to gain their approval.

The Great Seal, the mark of the Blessed and their continuing favor of our land, is more active than it has been for many a year. It feeds Court sorcery, the mark of the nobles—and that noble magic has strengthened, but it behaves erratically, as a newborn colt will stagger.

What does it mean?

News is scarce, rumor rife, and winter approaches with the tramp of boots and hooves, the creaking of siege engines, and the coughing of the Blood Plague. Those who take ill rarely recover. First the fever, then the chills, then the blood from mouth and nose and every other orifice.

And then, the death.

The people cry out for their King to take the sickness from them, and there are those who whisper he cannot…

… but that a Queen will.

I struck to kill.

The flesh, fat-rich and fed on luxury, parted under my blade. I rammed my sword, sworn to the service of Arquitaine’s King, through the heart of that same King.

The alarums were still ringing, but a great silence had descended upon me. Running feet and shouts resounded in the corridor, clash of steel and cries of pain.

Here in the Rose Room, where the King had been at his chai, there was nothing but a rattle. Henri gasped, the death-gurgle I have heard on many another’s lips.

I had killed for him too many times to count. Did he feel surprise that the tool he sharpened had thus turned in his hand?

My throat was dry as sandy Navarrin wastes. My heart pounded, a hare before hounds. Up to this moment it had been merely talk, a conspiracy I had played at catching out, biding my time. Now, with one decisive lunge, I had committed my soul entire to the enterprise.

I gave the blade one last vicious twist, freeing it of the suction of muscle and the scrape of ribs. The thrust had been true, years of daily practice on the drillfield distilled into murder. Henri’s elaborately curled hair fell in disarray, his mouth loose as if he sought to ask a question. He fell before he could give it voice, a bubble of bright blood bursting on his lips, so recently touching a dainty cake. He hit the floor in a sodden, shapeless lump of blue velvet and silk. The muscle of his youth had begun to run to fat, but his bones were broad and carried it well. Until now.

Death rarely grants a man’s frame any dignity.

I crouched easily, a duelist’s move once the duel is done, to watch an enemy’s last gasping moments. The sucking sound of a breath caught in a bloody throat, echoed by so many victims, now visited upon the man who had made me a weapon.

Years of service, striving, suffering. All gone in a single instant. “You should have let me have her,” I whispered. “ You are responsible for this.”

He made no reply, merely thrashed and choked his last. And as d’Orlaans’s Guard burst into the room, after having slaughtered those unfortunate enough to be on duty at Henri’s door, I came up from my crouch and met the first few in a clash of steel and confusion. Everything now depended on secrecy, and speed, and how willing I was to kill.

I suffered no qualms. But they took me anyway—d’Orlaans, the King’s brother, had suspected me, and set his Guard to capture instead of aid me. I had suspected as much, but I had not thought he would place a high premium upon capturing me alive. Pieces of the puzzle fell into place when they unleashed the first jolt of Court sorcery, a spell meant to dizzy and disable an opponent.

Somehow, I had let the King’s brother outplay me. It was hardly the first of my mistakes.

I could have screamed, the cheated howl of a wolf when the lamb is snatched from its teeth. Yet I did not, for the howl would have become a name, and I would not sully her name by speaking it in such a place.

One word, encapsulating the bait for this trap, the lure I had taken unknowing, like any stupid caged falcon at the mercy of its instinct.

Vianne.

I fell into darkness, holding the word behind my lips. The beating they meted out to me was only kisses compared to the agony of failure, the prize snatched from my grasp at the very last moment.

I was doomed.

Thief, liar, assassin, whore. Tale-bearer, spy, extortionist, confidante, scandal-smoother. A knife in the dark, poison in a cup, a shield and a defense on the battlefield as well as in the glittering whirl of Court. Puppetmaster, spymaster, whoremaster, brutal thug, protocol handler, cat’s-paw, pawn, troublemaker, cutthroat, fiend, pickpocket, swindler, brigand, pirate, kidnapper, alter ego, usurer, false witness…

This, then, is the Left Hand. And more.

The Hand does what must be done to cement the hold of the monarch on the realm, to protect the sovereign we swear fealty to—even at the cost of our own lives. Even at the cost of our honor.

There is only one word never applied to us, only one thing a Hand has never been.

Traitor.

To be the Left Hand is to be the most trusted of a monarch’s subjects, a position of high honor, though very few will know the truth of your face or name. Most of a Hand’s work is done in shadow, and well it should be. The Hand does those necessary things, by blood or by leverage, that a monarch cannot do. According to the secret Archives in the Palais d’Arquitaine, the first of us was Anton di Halier, who created the office in the time of Jeliane di Courcy-Trimestin—the Widowed Queen, history names her—who depended on Halier for her very life during the great wars, both internecine and foreign, of the Blood Years.

Those were winters when wolves both animal and Damarsene hunted in our land, and we have not forgotten. Nor have we forgotten the famine. Thin as the Blood Years , the proverb runs, and always accompanied by the avert-sign to ward off ill-luck.

I find it amusing the first Left Hand spent his service under a Queen. Sometimes.

We rode through the Quartier Andienne toward the white block of Arcenne’s Temple glittering on the mountainside: three of my Guard, Adrien di Cinfiliet the bandit of the Shirlstrienne, and I.

And her , silent on my mother’s most docile palfrey, hood drawn up over her dark head, moving like a slender, supple stem.

Hard campaigning, the cat and mouse of catching bandits or criminals, the melee of the battlefield, and the quick danger of Court-sorcery duels—all these I have endured, and I rarely think of fear. Rather, I think only on what must be done, and there is no room for terror. Yet Vianne di Rocancheil et Vintmorecy threatens to stop my idiot heart each time I glimpse her.

Читать дальше