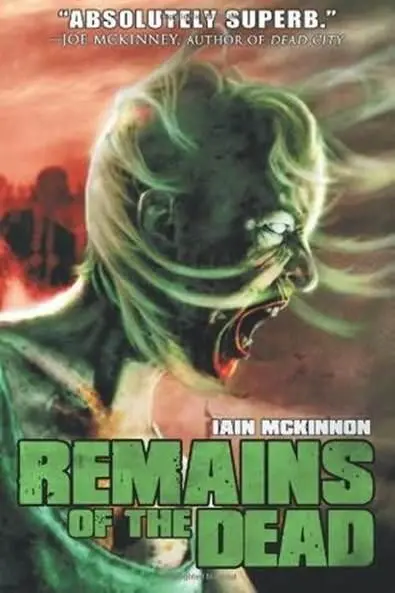

Iain McKinnon

Remains of the Dead

© 2011

“The heavens roared as with thunder and from the earth came the sound of moans. Storm clouds blackened the heavens and the world was shrouded in the stillness of death. Lightning cracked across the skies and flames flared up from the ground. From the bloated clouds there came rain, and the rain washed all life before it. When the flashes in the sky had died and the flames had withered all that remained was as ash.”

– Epic of Gilgamesh

If you’re reading this, you probably get the whole zombie thing. You understand why legions of fans love them so, and how the genre manages to produce a glut of new books and movies and comics every month without its fan base going into terminal burn out. Others have already noted that there is a parallel between zombie fandom’s ability to devour an ever-growing amount of new material and the insatiable appetites of the zombie itself, so I won’t go over that ground here. Most fans shrug their shoulders at such commentary anyway. Suffice it to say that if you’re a zombie fan, you don’t need an explanation. You just need more cool zombie shit.

Fair enough.

But what of those people who are still mystified by the zombie phenomenon’s growing popularity? What can we say to people who look at the zombie craze, shake their heads in disgust, and say, in all honesty, they see no redeeming value there whatsoever?

Well, first off, I’m not out to convert anyone. Some people just don’t get it, don’t care to, and won’t be bothered by any reasonable explanation of the zombie genre and what it’s saying about our lives and how we live them. More power to them. They are welcome to their opinion and I hope they have a nice day.

But there are quite a few people out there who are legitimately curious. They have watched the amazing proliferation of zombie-related material shambling into our lives and wondered if there’s something of value there. Perhaps, if they’re especially sensitive to social trends, they’ve even noticed that zombies have gone beyond the commercial success of The Walking Dead , World War Z and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies to infect our very language as well. They have successfully crossed over from mere pop culture references to accepted mainstream groupspeak. For example, following World War II we described people in shock as having the “2000 yard stare,” after the Tom Lea painting of a Marine from the Battle of Peleliu. But today, we’re just as likely to say “that person looks like a zombie,” or “has that zombie look in his eyes.” Going further, we see well respected professional economists such as Jeremy Grantham writing articles with titles like “Night of the Living Fed.” Professional forensic accountants, testifying before the Supreme Court and Senate select committees, speak of zombie businesses. Computer experts freely use terms like zombie terminals and zombie programs. And on and on.

So what does all this mean? What’s the point? Well, at a minimum, I think it suggests that once a concept becomes so integral to a society that it pervades the very language that society speaks, we are no longer free to dismiss that concept’s significance. And with the zombie, we now seem to be talking about something more than yet another horror fiction trope. We are watching the apotheosis of a B movie icon into a full fledged member of our modern day mythology.

That’s a grand claim, I know, but consider the shift in thinking behind the zombie’s recent elevation. Horror fiction has a long standing tradition of using monsters as metaphor. Frankenstein ’s creature played to our fear of science without a sense of moral responsibility. Dracula was, for the Victorians, an intensely sexual book, and an uncomfortable indictment of their cultural sensibilities. The space invaders of the 50s and 60s were thinly veiled Communists. Godzilla was the bastard stepchild of the bomb. Kurt Barlow was Stephen King’s personification of the disease killing America’s small towns. In each case, the monster was not only interesting, but stood for something.

The zombie too has been used as a metaphor. In fact, zombie writers have embraced this concept with gusto. George Romero used the zombie to criticize everything from racism to rampant consumerism. Max Brooks used World War Z as an amazingly subtle critique of world politics. Seth Grahame-Smith even managed to sneak in a little literary criticism with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies . The list goes on, but I think the point is made. The zombie as metaphor is simply part of a long literary tradition of making monsters matter.

Likewise, the zombie is nothing new in terms of what it is, which is basically your run of the mill revenant. It is a dead thing that has come back to pester the living, same as every ghost that’s come before it, same as Dracula and his imitators, same as Frankenstein ’s creature. All of which begs the question: if the zombie is just business as usual, how can I say it is something so completely new?

The answer lies in the zombie’s plurality. All of the monsters named above are distinctive because they are singular. There is just one of them. They are monstrous because they are so different from the humans they torment, and yet we can humanize them because they have distinctive personalities.

Not so the zombie. The zombie, as many writers have pointed out (myself included), is a blank slate upon which nearly any fear or social commentary can be projected.

And of course, there’s the fact that you never get just one zombie. You get wave upon relentless wave of them. Yes, they are plodding and stupid, but they are endowed with a single-mindedness that is as frightening as it is total. The individual zombie is nothing special. Detestable, yes. Frightening, certainly. One might safely say that a walking corpse is profound without being accused of waxing hyperbolic. But a single zombie is not an insurmountable obstacle. Even those who have never seen a zombie movie, or read a Max Brook book, know how to dispatch it. Destroy the brain with a gunshot or blunt object and the deed is done. Simple as that. Repeat as many times as necessary, or until you and your small band of survivors are all dead.

This leads, naturally enough, to the most common criticism of zombie fiction. Detractors accuse the genre, perhaps rightly, of being somewhat static. There is little content, they say, beyond the tidal motion of zombie violence, where the dead advance, are repelled, advance again, get repelled again, and so on until the reader grows numb and the continuing survival of the characters pointless. Why is this popular, they ask.

I would argue that this tidal motion, its endless repetition, is exactly what gives the genre its vitality.

Let me explain.

Modern life has a tediousness to it that is almost tragic. We go to work on Monday and begin the soul-sucking process of wading through an endless stream of bullshit emails. We move an endless amount of paperwork from pile A to pile B, then back again. We fill out forms that lead to more forms. Work takes on a painful sort of circularity, like dogs at the racetrack sprinting after fake rabbits. Those of you working retail know this pain at the molecular level.

Given the seeming pointlessness of it all, is it any wonder that the human spirit seeks to rebel? Is it any wonder that our creative minds seek to put a face on so much circularity, and annihilate it?

That’s where books like the one you hold in your hands come in. With Remains of the Dead , Iain McKinnon has harnessed the caged rage of the modern worker, and given him back his defiant roar. The war he describes is of course one of attrition. Zombies attack and people die. And this happens again and again.

Читать дальше