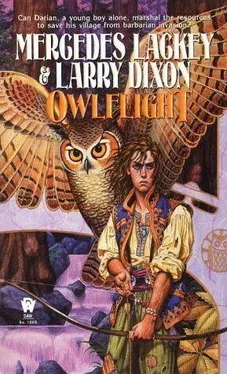

Mercedes R. Lackey and Larry Dixon.

One

The air was warm, the summer day flawless, and Darian Firkin was stalling, trying to delay the inevitable, and he knew it. He had hopes that if he just lingered enough on this task of wood gathering, his Master might forget about him - or something more urgent than the next lesson might come up before Wizard Justyn got himself organized. It was worth a try anyway, since the very last thing Darian wanted on this fine sunny day was to be cooped up in that musty old cottage. It was worth any amount of physical work to be saved from that fate.

He took a deep breath of the balmy air, laden with the scent of curing hay, damp earth, and growing things, and added another cut quarter-log to his burden of three, the bark and rough wood catching on his shirt and leaving bits of dirt and moss smeared on the sleeve. Would four be enough to qualify as a load? Probably. He headed for the cottage.

Justyn’s cottage decayed on the edge of the village, on the side farthest from the bridge and the road, closest to the Forest. The village itself was a tight little square of cottages with three finer houses, all arranged in neat rows around the village square; the fields farmed by the inhabitants of Errold’s Grove stretched out on either side along the riverbank, but on the back side there was nothing but a single field of corn and a small meadow where goats and sheep were kept in the winter. Behind all of that was the forest. If he paused for a moment and listened, it wasn’t at all difficult to hear the voice of the woods from where Darian stood - all the little rustling and murmurings, the birdsong and animal calls. Sometimes that was a torment, on days when Justyn set him some fool task that kept him pent in the cottage from dawn to dusk.

He put down his burden on the pile at the side of the dilapidated cottage and returned for more.

He carefully selected three small pieces of chopped wood from the large communal pile; the woodpile lay at the back of the right-hand side of the village of Errold’s Grove. He tucked them under his arm and carried them toward the rick-holder at the side of Wizard Justyn’s tiny cottage. Every day that it was possible, the village woodcutter went out with a team of oxen to find and bring back deadfall from the Pelagiris Forest. He never went far, but then, he never had to; the trees in the Pelagiris were enormous, with trunks so big that six men could stretch their arms around one and not have their fingers touch, and one fallen tree would supply enough wood for the whole village for a month. Every time there was a storm, at least one tree or several huge branches would come crashing down. The woodcutter did nothing at all but cut wood; no farmwork, no herding. The villagers supplied him in turn with anything he needed, and since he had no wife nor apprentice, the women took it in turn to cook for him, clean his little hut, and sew, wash, and mend his clothing. The woodcutter was not a bright man, nor one given at all to much thought, so he found the arrangement entirely to his satisfaction - and since the villagers never went into the Forest anymore if they didn’t have to, it was entirely to theirs as well.

Darian wished they had apprenticed him to the woodcutter instead of the wizard, but he hadn’t had any say in the matter. After all, as an orphan who had been left to the village to care for, he should be grateful that they gave him any sort of care at all. At least that was what they all told him, loudly and often.

The cottage was hardly longer than the wood-rick, built strongly at one time, of weathered, gray river rock with a thatched roof of broomstraw in which birds twittered all spring and summer long. That twittering was the first thing Darian heard every morning when he woke up. It was an adequate enough - little cottage by the standards of the village, but it seemed badly cramped to Darian, and always smelled slightly musty, with an undertone of bitter herbs and dust. No one ever cleaned it but Darian, so perhaps that was the reason for the aroma. He didn’t really despise the place, since after all, it was shelter, but it didn’t really feel like the home the other villagers and his Master tried to convince him it was.

When he reached the cottage and the upright supports that would hold exactly one measured rick of wood between them, he set each piece down on the half-rick already piled there with exacting care, distributing them with all the concentration of a fine lady making a flower arrangement. Only when they were balanced precisely to his liking did he return for another three logs. He listened carefully for any sound of life inside the cottage, for after Justyn had told him to replenish their fuel, Darian had left his Master muttering over a book, and Darian had hopes that Justyn might get so involved that he wouldn’t notice that Darian was taking a very long time to fetch wood from a few yards away.

There was no sound from inside the cottage, and Darian ambled off slowly, making as little noise as possible until he was out of easy hearing distance. The village was fairly quiet at this time of day, with most people working in the fields. Only a few crafters had work to keep them in their workshops at this time of year; most of the things that people needed they had to make for themselves these days, or hope that someone else in the village had the skills they lacked. Leather and fur were available in abundance, but the tanner worked hides mostly in the fall, and there was no official cobbler since Old Man Makus died. The blacksmith did all metal work needed, and with forty-odd families to provide for, he generally had enough work to keep him busy all of the time. The miller was also the baker, keeping flour and bread under the same roof, so to speak. He baked almost all of the bread and occasional sweets for the village, so that only one person would have to fire up and tend an oven. Women would often put together a stewpot or a meat pie or set of pasties for the evening dinner, and take it to him to put just inside the oven in the morning. Then they could go out to work the fields, and fetch the cooked meal back when the family returned for dinner. The womenfolk of Errold’s Grove did their own spinning, weaving, and sewing, mostly during the long, dark hours of winter, which was when the men made crude shoes and boots, mended or made new harnesses and belts, and carved wooden implements. Once every three or four months, everyone would take a day off work to make pots, plates, storage jars, and cups of clay from the banks of the Londell River, and in a few days when those articles were dry, the baker and the woodcutter would fire them all at once. Those went into a common store from which folk could draw whatever they needed until it was time to replenish the crockery again. The only things that had to be brought in from outside were objects of metal that required more skill than the blacksmith had, such as needles and pins, and bar-stock for the smith. Virtually everything else could be and was made by the people living here. The village was mostly self-sufficient, which was a source of bitter pride, for no one wanted to come here anymore. Errold’s Grove could have dropped off the face of the world and no one would miss it.

I certainly wouldn’t, Darian thought with bitterness of his own.

He had to pass through one of the busier corners of the village to reach the woodpile, going around both the smithy and the baker. The savory scent of bread coming from the door of the bakery told the boy that Leander was removing loaves from the big brick oven that took up all of the back half of his shop. As for the smith, he was obviously hard at work, as the smithy rang with the blows of hammer on anvil, there was a scent of hot metal and steam on the breeze, and smoke coming from the smokehole in the roof. Leander wouldn’t pay any attention to Darian as he passed, but there was a chance that the smith might.

Читать дальше