Death it seemed had cemented the curse firmly into a place of power. Or, it was Parna’s punishment.

Winter entered Amnos. Now was the time of long nights.

Clirando suffered it as best she could. When an alarm rang from the town’s brazen gongs, she leaped down the streets leading her band among the other warriors. Pirates were trying their luck again, made hungry by lean weather. They were beaten back into the sea. Clirando’s band did well, and sustained no casualties.

As the season moved toward spring, Clirando took herself in hand. The physician had already supplied her with an herbal medicine, which scarcely had an effect. Now she gained a stronger one. With its aid, every third or fourth night she was able to sleep two or three hours—though waking always with a heavy head and sickened stomach.

The bane will die away in its own time, like a venomous plant. I must ignore it, which will lessen its hold on me .

She pushed the burden from her, would not think of it by day, and lay reading through the nights.

Strangely, her body, young and fit, acclimatized to sleep loss, even if, on the third or fourth evening without slumber, sometimes she would see phantoms moving under trees or against walls—tricks of her tired eyes. Surely not real?

The priestess she consulted listened carefully to all Clirando told her. The priestess, who had been a warrior too in her youth, and was now middle-aged and stout, told Clirando gently, “And you have not mourned Araitha.”

“No, Mother. I’ve made offerings to the goddess for her sake, and put flowers by the altars in Araitha’s name. But I can’t mourn. I—I’m angry still. Disgusted still.”

“Yet you fought her and bested her and ruined her life in Amnos.”

“Do you mean I killed her?” Clirando stared. “It was because she had to go away that she died.”

“No. It wasn’t you that caused her drowning. The sea and the wind did that. But you broke her spirit, Clirando. Why else did she curse you in that way?”

“She could have wished me dead.”

“I think,” said the priestess quietly, “she preferred you to live and suffer. Thestus did not curse you. He didn’t care enough, or love enough. But Araitha was your sister. Measure her feeling for you by her last acts.”

“What shall I do?”

“Like all of us, Clirando, you can only do what you are able. Do that.”

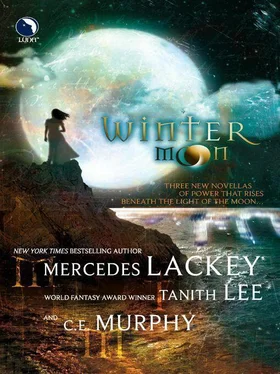

The moon, which by now figured so vividly in Clirando’s sleepless nights, began to be important to all the town—indeed to all the known world, from Crentis to Rhoia, and the burning southern deserts of Lybirica.

Every sixteen or seventeen years, through the strange blessing of the gods, there would come seven nights of midsummer when every night the moon would be full: seven nights together of the great white orb, coldly glowing as a disk of purest marble lit from within by a thousand torches.

The last such time had been in Clirando’s earliest childhood. She had only the dimmest memory of it, of her mother leading her up among the family on the roof each night to see—and of all the house roofs of Amnos being similarly crowded with people, who let off Eastern firecrackers in spiraling arcs of gold and red. Among Clirando’s band, only Erma and Draisis had never seen the seven full moons.

But all of them had heard of the Moon Isle. Even Thestus, come to that. He had compared Clirando to its unlovely rocks when they fought.

The Isle lay out in the Middle Sea, beyond Sippini. It was sacred and secret but, as was also well-known, on every occasion of the Seven Nights, certain persons had to go there, to honor and invoke the moon’s power.

Amnos would send its delegation of priests and priestesses. Sometimes others were selected to sail to the Isle. How they were chosen was never made public, and no one was permitted to speak—or ever did so—of what took place upon the island. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of the silence, theories abounded. The Isle was full of dangerous and terrible beasts, also of spirits and demons. It was a spot of ultimate ordeal and test—and some of those sent there had not returned.

Clirando herself had never speculated unduly. She had been too busy, too fulfilled in her life.

The same priestess was waiting for her when she answered the temple’s summons, and entered the shrine beside the main hall.

In the altar light below the statue of Parna, the dumpy older woman had gained both grace and presence.

“I have something to tell you, Clirando.”

“Yes, Mother?”

“You, and the six girls of your band, have been selected for an important duty.”

“Certainly, Mother. We’ll be glad to see to it.”

“Perhaps not.” The faintest nuance went over the priestess’s face. It was an unreadable expression—caused only, maybe, by the flicker of the altar lamp. “You seven are to travel to the Moon Isle.”

Clirando felt her heart trip over itself. She swallowed and said, “To the Isle?”

“Yes. You will leave in ten days, in order to be there at the commencement of the Moon Month.”

“Mother—this is an honor for us—but none of us have any notion of what we must do when we arrive.”

“None have,” said the priestess flatly.

“But then—”

“Clirando. This is both an honor for you, as you say, a reward for your valor and care in the past—and a penance. A privilege and a trial. You’ll have heard disturbing things of the place, yes?”

“Yes, Mother. I thought most of them fanciful.”

“Forget that impression. The Isle is supernatural and may produce anything. It is a place half in this world and half elsewhere. In spots, they say, it opens on the country of the moon itself. For philosophers have decided the moon is not what it appears, a disk, but rather a world, an unlike mirror to our own. Therefore anticipate magic, and great danger. Sacrifice is common on the Isle. So is death. But too the land is mystical and profound, and from death life may spring. There is a saying, a closed eye may sometimes see more there than one which stares. Do you consent to go?”

“Mother— I consent. But my girls—”

“Have no fear for them. They will be safer than you. You, Clirando, are the one the Isle requires. Human presence on it invokes the power of the moon, her cold fire. But sometimes pain is needed in the process, but not from all.”

Clirando felt a shadow fall on her, like a heavy cloak for traveling. Her sleep-starved eyes half glimpsed Araitha suddenly, standing there in the shade behind the goddess’s statue, motionless, with face averted.

“This is my true punishment, then.”

“You may see it as such,” said the priestess. “Or as a chance at salvation. The seas at this time of year are calm as honey. The voyage will last no longer than nineteen days, and perhaps rather less. Go now and tell your band. Pack anything you may need, for battle or for mere existence.”

1

Landscape

Across night and water, in darkness: the island. There was no moon tonight. Tomorrow was the moon’s First Night.

“Clirando, do you see?”

“I see. The beacons are burning.”

High up, the coastal cliffs were gemmed with them, drops of brilliant fire, each one separated from the next by many miles.

They were like eyes, watching, as the boat came in. Nothing else was to be seen, but the luminous rollers of the surf on the shore.

The galley had put them off as soon as the sun set in the Middle Sea. The Isle was visible, a black dot far away. The captain told Clirando the water there was too shallow for his ship, but also no man or woman, unless called or ordered to the Isle, might go in any nearer.

Читать дальше