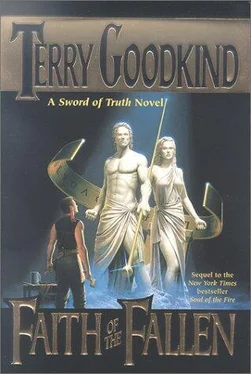

Terry Goodkind

Faith of the Fallen

To Russell Galen, my first true fan, for his steadfast faith in me

She didn’t remember dying.

With an obscure sense of apprehension, she wondered if the distant angry voices drifting in to her meant she was again about to experience that transcendent ending: death.

There was absolutely nothing she could do about it if she was.

While she didn’t remember dying, she dimly recalled, at some later point, solemn whispers saying that she had, saying that death had taken her, but that he had pressed his mouth over hers and filled her stilled lungs with his breath, his life, and in so doing had rekindled hers. She had had no idea who it was that spoke of such an inconceivable feat, or who “he” was.

That first night, when she had perceived the distant, disembodied voices as little more than a vague notion, she had grasped that there were people around her who didn’t believe, even though she was again living, that she would remain alive through the rest of the night. But now she knew she had; she had remained alive many more nights, perhaps in answer to desperate prayers and earnest oaths whispered over her that first night.

But if she didn’t remember the dying, she remembered the pain before passing into that great oblivion. The pain, she never forgot. She remembered fighting alone and savagely against all those men, men baring their teeth like a pack of wild hounds with a hare. She remembered the rain of brutal blows driving her to the ground, heavy boots slamming into her once she was there, and the sharp snap of bones. She remembered the blood, so much blood, on their fists, on their boots. She remembered the searing terror of having no breath to gasp at the agony, no breath to cry out against the crushing weight of hurt.

Sometime after—whether hours or days, she didn’t know—when she was lying under clean sheets in an unfamiliar bed and had looked up into his gray eyes, she knew that, for some, the world reserved pain worse than she had suffered.

She didn’t know his name. The profound anguish so apparent in his eyes told her beyond doubt that she should have. More than her own name, more than life itself, she knew she should have known his name, but she didn’t.

Nothing had ever shamed her more.

Thereafter, whenever her own eyes were closed, she saw his, saw not only the helpless suffering in them but also the light of such fierce hope as could only be kindled by righteous love. Somewhere, even in the worst of the darkness blanketing her mind, she refused to let the light in his eyes be extinguished by her failure to will herself to live.

At some point, she remembered his name. Most of the time, she remembered it.

Sometimes, she didn’t. Sometimes, when pain smothered her, she forgot even her own name.

Now, as Kahlan heard men growling his name, she knew it, she knew him.

With tenacious resolution she clung to that name—Richard—and to her memory of hint, of who he was, of everything he meant to her.

Even later, when people had feared she would yet die, she knew she would live. She had to, for Richard, her husband. For the child she carried in her womb. His child. Their child.

The sounds of angry men calling Richard by name at last tugged Kahlan’s eyes open. She squinted against the agony that had been tempered, if not banished, while in the cocoon of sleep. She was greeted by a blush of amber light filling the small room around her. Since the light wasn’t bright, she reasoned that there must be a covering over a window muting the sunlight, or maybe it was dusk. Whenever she woke, as now, she not only had no sense of time, but no sense of how long she had been asleep.

She worked her tongue against the pasty dryness in her mouth. Her body felt leaden with the thick, lingering slumber. She was as nauseated as the time when she was little and had eaten three candy green apples before a boat journey on a hot, windy day. It was hot like that now: summer hot. She struggled to rouse herself fully, but her awaking awareness seemed adrift, bobbing in a vast shadowy sea. Her stomach roiled. She suddenly had to put all her mental effort into not throwing up. She knew all too well that in her present condition, few things hurt more than vomiting. Her eyelids sagged closed again, and she foundered to a place darker yet.

She caught herself, forced her thoughts to the surface, and willed her eyes open again. She remembered: they gave her herbs to dull the pain and to help her sleep. Richard knew a good deal about herbs. At least the herbs helped her, drift into stuporous sleep. The pain, if not as sharp, still found her there.

Slowly, carefully, so as not to twist what felt like double-edged daggers skewered here and there between her ribs, she drew a deeper breath.

The fragrance of balsam and pine filled her lungs, helping to settle her stomach. It was not the aroma of trees among other smells in the forest, among damp dirt and toadstools and cinnamon ferns, but the redolence of trees freshly felled and limbed. She concentrated on focusing her sight and saw beyond the foot of the bed a wall of pale, newly peeled timber, here and there oozing sap from fresh axe cuts. The wood looked to have been split and hewn in haste, yet its tight fit betrayed a precision only knowledge and experience could bestow.

The room was tiny; in the Confessors’ Palace, where she had grown up, a room this small would not have qualified as a closet for linens. Moreover, it would have been stone, if not marble. She liked the tiny wooden room; she expected that Richard had built it to protect her. It felt almost like his sheltering arms around her. Marble, with its aloof dignity, never comforted her in that way.

Beyond the foot of the bed, she spotted a carving of a bird in flight.

It had been sculpted with a few sure strokes of a knife into a log of the wall on a flat spot only a little bigger than her hand. Richard had given her something to look at. On occasion, sitting around a campfire, she had watched him casually carve a face or an animal from a scrap of wood. The bird, soaring on wings spread wide as it watched over her, conveyed a sense of freedom.

Turning her eyes to the right, she saw a brown wool blanket hanging over the doorway. From beyond the doorway came fragments of angry, threatening voices.

“It’s not by our choice, Richard . . . We have our own families to think about . . . wives and сhildren . . .”

Wanting to know what was going on, Kahlan tried to push herself up onto her left elbow. Somehow, her arm didn’t work the way she had expected it to.

Like a bolt of lightning, pain blasted up the marrow of her bone and exploded through her shoulder.

Gasping against the racking agony of attempted movement, she dropped back before she had managed to lift her shoulder an inch off the bed. Her panting twisted the daggers piercing her sides. She had to will herself to slow her breathing in order to get the stabbing pain under control. As the worst of the torment in her arm and the stitches in her ribs eased, she finally let out a soft moan.

With calculated calm, she gazed down the length of her left arm. The arm was spitted. As soon as she saw it, she remembered that of course it was. She reproached herself for not thinking of it before she had tried to put weight on it. The herbs, she knew, were making her thinking fuzzy.

Fearing to make another careless movement, and since she couldn’t sit up, she focused her effort on forcing clarity into her mind.

She cautiously reached up with her right hand and wiped her fingers across the bloom of sweat on her brow, sweat sown by the flash of pain. Her right shoulder socket hurt, but it worked well enough. She was pleased by that triumph, at least. She touched her puffy eyes, understanding then why it had hurt to look toward the door. Gingerly, her fingers explored a foreign landscape of swollen flesh. Her imagination colored it a ghastly black-and-blue. When her fingers brushed cuts on her cheek, hot embers seemed to sear raw, exposed nerves.

Читать дальше