But Pyetr’s condition was excuse enough for pilferage, he was sure. He filled the washing bowl from the water barrel by the door and washed the dirt off his own hands, spattering little pockmarks into the old dirt on the board floor. There was no cloth to dry his hands, and he wiped them finally on his muddy shirt, hearing in his imagination aunt Ilenka’s stinging complaint of this cottage, its debris, its dust-But it was wonderful. It was with its rustic clutter rich as a tsar’s palace in terms of things they needed; and he laid eyes on a bowl and took it back to the fireside, dipping up a little of the stew for Pyetr, and kneeling to put it into his hands.

“I’m looking for the drink,” he said. “Eat what you can.” He thought then that if he was borrowing stew for two people, he ought to add a bit to it, so he pulled down a couple more large turnips from the strings, found a knife on the table and diced them up fine, added a bit more water, a little bit of salt—a touch of dillweed and savory were what it wanted, he decided, after one and the next tastings that amounted to several mouthfuls.

He found the dill hanging in a bunch from a rafter, crushed it in his hands and tossed it in and stirred it; and took a bowl for himself before he swung the hook back full over the fire to boil.

Pyetr had finished his, down to scouring the bowl and licking his finger; and Pyetr said, wistfully, “Can you find that drink at all?”

“I don’t know.” Sasha set his stew down on the hearth and investigated jugs one after the other, staggering, he was so tired, and afraid he might crack one, his hands were so unsteady. He found mostly oils of various sort, and once something that made him sneeze; he was anxious about meddling with things that smelled more like poisons than cooking oil. Untidy housekeeping, he reasoned to himself; simples; poisons to kill vermin: The Cockerel’s shed held such things. Aunt would never approve them in the house; but, then, The Cockerel had too many hands in the kitchen to be proof against mistakes.

He found the trap in the floor, a cellar as dark and cellar-smelling as he feared it would be as he got down on his knees and gingerly peered inside. He could see nothing but the wooden steps, the wooden floor below, the hint of jars along the wall, hanging bits of rope and such…

It was plainly thievery he was contemplating; and there were warders in a house, no matter what Pyetr believed. The hair prickled on his nape as he eased his way down the narrow steps into the damp, cool air, only five or so steps down into the musty dark, a short search of the shelves down below. He found jugs of likely shape, took one into his arms, unstopped and sniffed it.

Indeed. No doubt about this one. No poison and no noxious oil.

He heard something then on the far side of the cellar, a small scratching that might be vermin.

He did not fly up the steps; he was calm and brave and quietly whispered, reasoning with himself that no House-thing was going to object to a jug of vodka if it had not objected to the door opening:

“Please excuse me. My friend really does need it. We’re not thieves.”

He poured a little on the floor for the House-thing, if it was listening. Then he scrambled up the steps and let the trap down gently, his heart thumping with fright.

He felt the fool, then. Talking to rats, Pyetr would say—he wished Pyetr would say, and show some liveliness; but Pyetr looked much beyond jokes at the moment, his dirty, stubbled face lined with pain and patience.

“I’m hurrying,” Sasha said. He found a bowl on the kitchen table and poured, and brought it to Pyetr; he spied a pile of quilts in the corner by the bed and brought them to Pyetr too, heaping them around him against the warm stones while Pyetr drank, cupping the bowl in dirty, bloody hands and looking so weak and so miserable—as if Pyetr was suddenly beginning to sink, the way sick people would when their strength ran out and fever set in.

Someone had to do something soon, he thought. He had doctored horses enough to know that, but the thought of dealing with a wound going bad all but turned his stomach. He hoped for the ferryman returning, hoped he would know better what to do; but at least he could have hot water ready for compresses, and if there was only wormwood and sweet oil somewhere in the house that was a start on things.

So he put water to heat on a second pothook, and sat down a moment with his bowl of cooling stew—not even his sore throat and the prospect in front of him could discourage him from that. Pyetr at least seemed happier and more comfortable, placidly watching him.

But Pyetr looked to be in pain for a moment. Sasha watched him, the spoon in midair. Pyetr said, “It’s all right.” And extraneously, a line between his brows: “What’s in the cellar?”

“I don’t know, stuff. Jars. Turnips.” He almost said, rats; he wanted something to distract Pyetr from his misery, which was what he thought Pyetr wanted. He was afraid, making light of things: it went against his nature. He made the effort, nonetheless. “Something went bump. I came up.”

“I thought you did,” Pyetr said muzzily, and the line left his brow, as if he had been worrying about his quick run up the steps, but, then, he was a little drunk. “Not the owner, then.”

“No,” Sasha assured him, waiting for Pyetr to make some gibe about bogles, but the line came back to Pyetr’s brow and Pyetr’s lips made a white line.

That finished Sasha’s appetite. “I’ve got some water warming,” he said. “Want to wash?”

Pyetr seemed to agree with that. Sasha got up and got a cloth and soaked it for Pyetr to wash his face and hands. And carefully then, delicately, Pyetr not objecting, he worked Pyetr’s coat loose.

Blood soaked the shirt beneath it, repeated old stains and a large, bright new one.

“Wounds do that,” Pyetr said confidently. But Pyetr looked both sick and worried at the sight of it.

“Another drink?” Sasha asked.

Pyetr nodded. Sasha fetched him one, and Pyetr sipped at it slowly, resting his head back against the stones while Sasha untied his belt, pulled up his shirt beneath his arms, and tried to work the bandaging loose.

“Ow!” Pyetr gasped suddenly, and drink slopped from the bowl onto his stomach and rolled down; some had spilled on the bandaging. “Oh, god,” Pyetr moaned, while it soaked in, “oh, god—” He went white then and all but fainted against the fireside stones. He could not hold the bowl any longer. Sasha took it from his hand and Pyetr sank back against the wad of quilts, broken out in sweat.

Sasha’s own hands were shaking. It was a worse wound than anything the horses had ever done to themselves. It was far worse than he knew how to deal with, and he knew absolutely nothing other to do than to soak the bandage free.

“A little tender,” Pyetr gasped, between breaths. “Just let it alone tonight. Morning’s soon enough.”

“It’s going bad,” Sasha said, shivering despite the fire beside him.

“Wounds always get a little fever. It means it’s healing.”

“Not with the horses,” Sasha said. “I’d soak it in warm water and pack it with herbs.”

Pyetr shook his head. “We don’t know who owns that pot of stew. If you go at that again I won’t be fit for anything, and I don’t think that’s—”

Someone was walking outside. Someone slowly stumped up the log walk and Sasha’s heart began to beat with a heavy thump-thump-thump as Pyetr groped after his sword. “Get me on my feet,” Pyetr said, and Sasha, finding no other protection for them, put his shoulder under Pyetr’s good side and heaved, desperately, while Pyetr flailed out after the stonework and got a grip on the mantle.

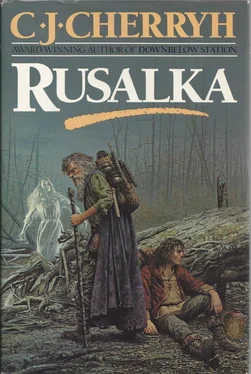

The bar lifted, the door swung back, and a skinny, thin-bearded old man in a ragged cloak stopped still in the open doorway, firelit against the dark.

Читать дальше