“Who is Podarge?”

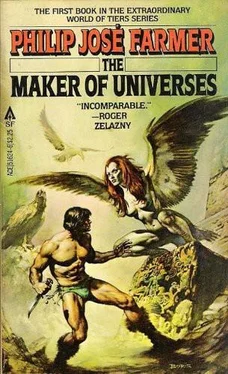

“She is, like me, one of the Lord’s monsters. She, too, once lived on the shores of the Aegean; she was a beautiful young girl. That was when the great king Priamos and the godlike Akhilleus and crafty Odysseus lived. I knew them all; they would spit on the Kretan Ipsewas, the once-brave sailor and spearfighter, if they could see me now. But I was talking of Podarge. The Lord took her to this world and fashioned a monstrous body and placed her brain within it.

“She lives up there someplace, in a cave on the very face of the mountain. She hates the Lord; she also hates every normal human being and will eat them, if her pets don’t get them first. But most of all she hates the Lord.”

That seemed to be all that Ipsewas knew about her, except that Podarge had not been her name before the Lord had taken her. Also, he remembered having been well acquainted with her. Wolff questioned him further, for he was interested in what Ipsewas could tell him about Agamemnon and Achilles and Odysseus and the other heroes of Homer’s epic. He told the zebrilla that Agamemnon was supposed to be a historical character. But what about Achilles and Odysseus? Had they really existed?

“Of course they did,” Ipsewas said. He grunted, then continued, “I suppose you’re curious about those days. But there is little I can tell you. It’s been too long ago. Too many idle days. Days?—centuries, millenia!—the Lord alone knows. Too much alcohol, too.”

During the rest of the day and part of the night, Wolff tried to pump Ipsewas, but he got little for his trouble. Ipsewas, bored, drank half his supply of nuts and finally passed out snoring. Dawn came green and golden around the mountain. Wolff stared down into the waters, so clear that he could see the hundreds of thousands of fish, of fantastic configurations and splendors of colors. A bright-orange seal rose from the depths, a creature like a living diamond in its mouth. A purple-veined octopus, shooting backward, jetted by the seal. Far, far down, something enormous and white appeared for a second, then dived back toward the bottom.

Presently the roar of the surf came to him, and a thin white line frothed at the base of Thayaphayawoed. The mountain, so smooth at a distance, was now broken by fissures, by juts and spires, by rearing scarps and frozen fountains of stone. Thayaphayawoed went up and up and up; it seemed to hang over the world.

Wolff shook Ipsewas until, moaning and muttering, the zebrilla rose to his feet. He blinked reddened eyes, scratched, coughed, then reached for another punchnut. Finally, at Wolff’s urging, he steered the sailfish so that its course paralleled the base of the mountain.

“I used to be familiar with this area,” he said. “Once I thought about climbing the mountain, finding the Lord, and trying to…” He paused, scratched his head, winced, and said, “Kill him! There! I knew I could remember the word. But it was no use. I didn’t have the guts to try it alone.”

“You’re with me now,” Wolff said.

Ipsewas shook his head and took another drink. “Now isn’t then. If you’d been with me then… Well, what’s the use of talking? You weren’t even born then. Your great-great-great-great-grandfather wasn’t born then. No, it’s too late.”

He was silent while he busied himself with guiding the sailfish through an opening in the mountain. The great creature abruptly swerved; the cartilage sail folded up against the mast of stiff bone-braced cartilage; the body rose on a huge wave. And then they were within the calm waters of a narrow, steep, and dark fjord.

Ipsewas pointed at a series of rough ledges.

“Take that. You can get far. How far I don’t know. I got tired and scared and I went back to the Garden. Never to return, I thought.”

Wolff pleaded with Ipsewas. He said that he needed Ipsewas’ strength very much and that Chryseis needed him. But the zebrilla shook his massive somber head.

“I’ll give you my blessing, for what it’s worth.”

“And I thank you for what you’ve done,” Wolff said. “If you hadn’t cared enough to come after me. I’d still be swinging at the end of a rope. Maybe I’ll see you again. With Chryseis.”

“The Lord is too powerful,” Ipsewas replied. “Do you think you have a chance against a being who can create his own private universe?”

“I have a chance,” Wolff said. “As long as I fight and use my wits and have some luck, I have a chance.”

He jumped off the decklike shell and almost slipped on the wet rock. Ipsewas called, “A bad omen, my friend!”

Wolff turned and smiled at him and shouted, “I don’t believe in omens, my superstitious Greek friend! So long!”

He began climbing and did not stop to look down until about an hour had passed. The great white body of the histoikhthys was a slim, pale thread by then, and Ipsewas was only a black dot on its axis. Although he knew he could not be seen, he waved at Ipsewas and resumed climbing.

Another hour’s scrambling and clinging on the rocks brought him out of the fjord and onto a broad ledge on the face of the cliff. Here it was bright sunshine again. The mountain seemed as high as ever, and the way was as hard. On the other hand, it seemed no more difficult, although that was nothing over which to exult. His hands and knees were bleeding and the ascent had made him tired. At first he was going to spend the night there, but he changed his mind. As long as the light lasted, he should take advantage of it.

Again he wondered if Ipsewas was correct about the gworl probably having taken just this route. Ipsewas claimed that there were other passages along the mountain where the sea rammed against it, but these were far away. He had looked for signs that the gworl had come this way and had found none. This did not mean that they had taken another path—if you could call this ragged verticality a path.

A few minutes later he came to one of the many trees that grew out of the rock itself. Beneath its twisted gray branches and mottled brown and green leaves were broken and empty nutshells and the cores of fruit. They were fresh. Somebody had paused for lunch not too long ago. The sight gave him new strength. Also, there was enough meat left in the nutshells for him to half-satisfy the pangs in his belly. The remnants of the fruits gave him moisture to put in his dry mouth.

Six days he climbed, and six nights rested. There was life on the face of the perpendicular, small trees and large bushes grew on the ledges, from the caves, and from the cracks. Birds of all sorts abounded, and many little animals. These fed off the berries and nuts or on each other. He killed birds with stones and ate their flesh raw. He discovered flint and chipped out a crude but sharp knife. With this, he made a short spear with a wooden shaft and another flint for the tip. He grew lean and hard with thick callouses on his hands and feet and knees. His beard lengthened.

One the morning of the seventh day, he looked out from a ledge and estimated that he must be at least twelve thousand feet above the sea. Yet the air was no thinner or colder than when he had begun climbing. The sea, which must have been at least two hundred miles across, looked like a broad river. Beyond was the rim of the world’s edge, the Garden from which he had set out in pursuit of Chryseis and the gworl. It was as narrow as a cat’s whisker. Beyond it, only the green sky.

At midnoon on the eighth day, he came across a snake feeding upon a dead gworl. Forty feet long, it was covered with black diamond spots and crimson seals of Solomon. The feet that arrayed both sides grew out of the body without blessing of legs and were distressingly human-shaped. Its jaws were lined with three rows of sharkish teeth.

Читать дальше