“Phase one, check,” Yigal says to no one, though Misha and Alon Peri are with him. He turns to Peri. “This is really going to work?”

“Absolutely,” Peri says. Then: “All things being equal.”

“I never know what that means,” Yigal says. “What if their tin cans take other routes?”

“On the narrower streets, their turrets can’t turn,” Misha says. “All they can shoot is the tank ahead. Unless they’re totally incompetent, they’ll stick to the boulevards.”

“And the…devices?”

Peri beams with confidence. “Couldn’t be lower tech. They’ll be fine.”

“If not, this guy’s dead,” Misha says.

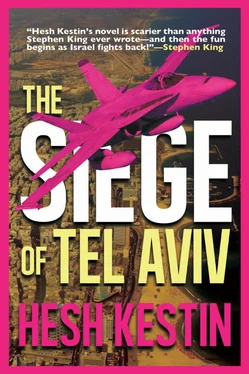

Yigal turns back to the window as the last of the F/A-18s flashes by. “If not,” he says, “we’re all dead.”

THE PRESIDENT IS AT the lake, popping open a bottle of Peroni Nastro Azzurro. He prefers this Italian brand, but can never drink it anywhere but Camp David. Where there are photographers, which to the president’s great annoyance is everywhere else, he makes a point of drinking Bud, Lone Star, Sam Adams. Election day is right around the corner.

With him are the members of an ad hoc war room, none of them in bathing attire.

“The Arabs are ready to roll,” Admiral Staley says. “No doubt about that.”

“Big?” the president asks. He dips a toe in the water. It is not quite as warm as he would like, but he still intends to swim out to the platform a half mile out. Two Boston Whalers—engines idling, each holding four Secret Service agents, one of them equipped with oxygen—stand by to accompany him.

“We invaded Iraq with less,” Staley says. “Over a thousand tanks, Jordanian, backed up by mechanized infantry, Egyptian those. Strung out all along the western border, there’s enough Syrian and Iraqi ground forces to surround Washington D.C.”

Shielding his eyes from the sun with both hands, Felix St. George peers out onto the lake—this is as artificial as his gesture, which is meant suggest he can be depended on for the long view. “Mr. President, if Israel has the capacity, this is the time they’ll effectuate.”

“You’re talking what, Felix—Armageddon?”

“Mr. President,” the security advisor says. “Do you recall the story of Samson?”

“Delilah gave him a haircut, that one?”

“That one, Mr. President. Sir, he pulled down everything around him.”

No slouch at gestures himself, the president hands Flo Spier his watch. “Flo?”

“Sir, if this goes nuclear, a radioactive cloud will cover the globe. Mr. President, I hate to sound cynical…”

“No, you don’t. Because you’re so good at it.” Now both the president’s feet are in the water. “Go ahead.”

“Mr. President, those Jordanian tanks better take out Tel Aviv before Tel Aviv takes out the world.”

The president stretches his arms over his head, then straight out, then stretches again. “Admiral?”

“Mr. President?”

“What are the odds? Am I going to get to see that blowjob movie tonight?”

“Mr. President, aside from the nuclear option, which doesn’t seem like they’ve got any way to deliver, Israel’s down to a few tanks, and they’re strung out in an easily punctured line. Sir, by the time you finish that film this evening, the State of Israel, such as it is, will no longer exist.”

The president chugs the last of his Peroni and, in a final gesture, hands the empty to Admiral Staley. “Well, I always said they should have put it on a travel poster,” the president says, turning to the lake. “Israel—see it while it exists.”

The president dives in, his smooth, even stroke barely disturbing the surface of the water as the two purring Boston Whalers full of Secret Service personnel follow at a discreet distance. Aside from the two small boats, the president has the entire lake to himself.

WITH NO HELICOPTERS OR observation planes, no drones and no access to Israel’s five orbiting satellites, Pinky and his senior staff have little choice but to climb as high as practical in one of Israel’s modest skyscrapers to view what is officially known as Phase II but which everyone involved in its planning thinks of as the Battle of Tel Aviv.

The building rises forty-five stories above the Diamond Exchange on the border that defines Tel Aviv proper from the municipality of Ramat Gan. Once separate geographical entities, the two have agglutinated, as Tel Aviv has with its other suburbs. From their observation post on the tenth floor—going any higher would isolate the IDF leadership should they need to descend quickly—Pinky and his officers have a 360-degree view of the city and its environs, including the Ayalon Highway which slices south to north. From here, they see the first of hundreds of Challenger tanks moving by fours on both sides of the divided highway, some branching off onto the broader streets leading west to the sea. As predicted, the tanks stick to the wider thoroughfares.

Pinky eases down his high-powered binoculars and turns to the others. “Those who are religious, you know what to do,” he says. “In fact, all of you. It’s an order. Pray.”

AS FOUR ROYAL JORDANIAN Apache helicopters hover at two thousand feet, seemingly endless columns of Jordanian armor push through the flimsy barriers of bed frames, derelict refrigerators, and abandoned cars surrounding Ghetto Tel Aviv and enter the city. From the point of view of the tank commanders, who toggle between front, rear, left, and right views on their screens, Tel Aviv is a ghost town, its boulevards empty, nothing in motion. Thirty feet above them, at regular intervals, white bed sheets serving as flags of surrender hang from taut cables. Indeed, the only movement is the sheets themselves as they stir in a light breeze coming off the Mediterranean.

Enclosed in their tanks, the officers and men of the Royal Jordanian Armored Corps are at once gratified and puzzled. There is nothing alive, not so much as a stray dog or cat. There wouldn’t be: all but the quickest have been eaten. The sheets give the city a strangely festive look as the tanks move into position.

FROM HIS PERCH ON the terrace of the second-floor apartment overlooking Ibn-Gvirol Street, his harness clipped to the cable, Cobi tightens his gas mask and launches down until he reaches the moving Challenger below, slips the clip from the cable, and drops to the roof of the slow-moving tank. Were he less focused on what he was trained over and over to do, he would see copies of himself alighting on every tank on the boulevard; were he in one of the Jordanian Apaches soaring over the city, he would see hundreds more. He clambers to the tank’s ventilator in the turret, pulls the foot-long brass tube from his belt, and smashes it down into the ventilator with his hammer.

By this time, the tank crew may be aware something untoward is happening, but like most main battle tanks, Challengers have 360-degree viewing capacity on the horizontal plane but are blind to anything happening immediately above or below. What is happening above is an example of the primitive overcoming the sophisticated. The ABC (Atomic, Biological, Chemical) filter on the intake vent of the Challenger is a soft multi-tissue membrane—it must be in order for clean outside air to enter the otherwise sealed tank cabin. Once that membrane is pierced, such as by a brass tube struck by a ballpeen hammer with sufficient force, the cabin is no longer secure.

The IDF planning group responsible for this breakthrough—and it is a breakthrough in more than figurative terms—first examined the feasibility of inserting a grenade into the cabin and thus neutralizing its crew of four on the spot, but since the objective is to utilize the enemy armor immediately, it was decided to use CS, commonly known as tear gas. The problem then was how to pierce the filtration membrane and fill the cabin with CS at once. Alon Peri provided the answer: a simple tube that, when hit in its center, engages a firing pin, while at the same time tearing through the filtration mesh.

Читать дальше