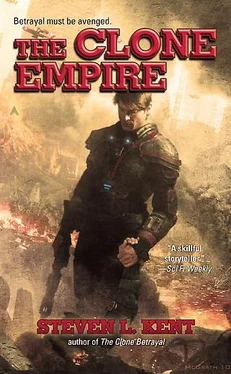

Steven Kent - The Clone Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Kent - The Clone Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Боевая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Clone Empire

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Clone Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Clone Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Clone Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Clone Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Are you sure he’s there?” I asked.

“He’s a hard man to miss,” Cabot said.

I watched the surroundings out the window as we drove through the city. We crossed a suspension bridge, and I saw a shoreline bustling with life. Rows of skyscrapers lined the freeway like the cliffs along a river canyon. “I have not seen a city like this for a while,” I said.

“Yes, sir. It’s like the war never came here,” Cabot agreed.

You can only dodge bullets for so long, I thought. These people might have ducked the Avatari; but the Unifieds would make up for it. The next war would begin in a day and a half.

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

“Evacuate the planet?” I asked. The suggestion was ridiculous. It didn’t matter what the Unified Authority had up its sleeve, evacuation was out of the question. “I have five hundred thousand men here.”

“I’m not just talking about your men, I mean the civilian population,” Freeman said. He sat unflinching, his eyes narrowed in on mine.

“That isn’t going to happen,” I said. Then I thought about what he had just said. “The Unifieds aren’t going after civilians.”

We sat alone in the camp commander’s office. The pictures on the walls were placed there for soldiers, not Marines. They showed scenes with tanks and gunships and fighting men wearing fatigues. The clock showed 22:13.

“You are talking about millions of people. I couldn’t evacuate them if I wanted to. I don’t have enough ships.”

“You’re going to need more,” Freeman agreed.

“You wouldn’t happen to have a few lying around that you could loan me?” I asked with so much sarcasm that even Freeman could not ignore it.

“I have twenty-five of them,” he said. “They carry a quarter of a million passengers apiece.”

That gave me pause. I would have accused him of joking, but Freeman never joked. He was more likely to build twenty-five gargantuan ships than tell a joke.

“Bullshit! Nothing but a planet can carry a quarter of a million people,” I muttered, though I already knew that the ships must exist.

“They’re barges,” Freeman said.

“Where the speck did you find something like that?” I asked; but as soon as I asked, I realized the only possible answer. I shelved that information away, Freeman was on the verge of showing me his hidden cards. Taking a deep breath, I asked, “Ray, why do we need to evacuate?”

Always enigmatic, Freeman did not answer. He studied me for a moment, his expression impassive, then he reached into his pocket and pulled out a small device that looked like a notepad with a screen. Whatever it was, it looked tiny in Freeman’s gigantic right hand.

He placed it flat on the table.

The two-way communicator was six inches long, less than three inches wide, and flat as a shingle. The edges of the communicator were shiny black plastic. The screen that filled the frame was already lit. A face I recognized stared up from it.

“Good morning, Harris,” said the familiar gravelly voice.

“Good morning,” I said, wondering if somewhere along the line, I had lost my mind.

“We hear you’ve been promoted to general. Congratulations.”

“Thank you,” I said, staring at the screen and trying to figure out its magic. Few people had earned my respect as thoroughly as Dr. William Sweetwater. He died more bravely than any man I knew.

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

William Sweetwater died on New Copenhagen. He led the team of scientists that unraveled the aliens’ technology. He was a brilliant, fearless dwarf who always referred to himself in the royal plural.

I started to ask Freeman if this was some sort of a prank, but he put up a hand to stop me. He had pointed the communicator toward me, so that the pin-sized camera mounted under the screen would not catch his movements, then he put up a finger across his lips.

On the screen, Sweetwater continued chatting amiably. He watched me with eyes that I had seen burned by toxic air. He spoke with lips I had seen blister so badly they burst. In this new incarnation, the little man was once again whole.

The diminutive scientist chattered on. “We hear you’ve been busy resurrecting planets, Harris.”

I almost spoke up when I heard his use of the word “resurrected.” He looked real enough, but any schoolkid could scan a photograph into a computer and convert it into a three-dimensional animation. Making the animation interactive, though, giving it the exact right voice and mannerisms, that would require familiarity with Sweetwater and extensive audio files. The character on the screen not only looked and sounded like Sweetwater, it acted like him.

“You mean the revolution?” I asked. Now Freeman waved his hand to stop me, then picked up the communicator and turned it toward himself.

“Doctor, give me a moment to speak with General Harris?” Freeman asked.

The avatar on the screen smiled, and said, “Certainly, Raymond.”

Freeman switched the two-way off, then told me, “He doesn’t know you are at war with the Unified Authority.”

“Of course he doesn’t, he’s been dead for three years,” I said. “The only thing going through his mind is worms.”

“He thinks he’s alive and that he has been assigned to the Clarke space station.” The Arthur C. Clarke Space Station, or the “Wheel,” as most people called it, was a scientific observation post on the extreme outer edge of the Orion Arm. The Wheel was huge, three miles in diameter. It took its name from a prehistoric science-fiction writer who had popularized ideas like spinning space stations and spaceflights to nearby planets.

“He doesn’t think anything,” I pointed out. “He’s dead. He’s more than dead, he’s incinerated. We left him lying next to a fifty-megaton bomb.”

“He may only be a V-job of Sweetwater, but he thinks he’s real, and we need to keep it that way,” Freeman said. “They replicated Sweetwater’s brain.”

“What about Breeze?” I asked. Arthur Breeze had been Sweetwater’s partner in science and his polar opposite. Sweetwater was barely four feet tall, plump, with a scraggly beard and long reddish brown hair. He was mildly cocky, acted hip, walked with a swagger.

Breeze, on the other hand, stood six-foot-four and weighed a bony buck fifty at best. He was forehead-bald past the crown of his head with a garland of cotton-fluff hair that ran between his ears but no lower. He wore thick glasses that were always smudged with fingerprints and dusted with dandruff. He had teeth the size of gravestones that would have looked just about right in the mouth of a horse.

“Breeze is in there, too,” Freeman said. “No point having one without the other.”

“In there? On the Wheel?”

“They believe they are alive and that they are on the Wheel for their own protection,” Freeman said.

“For their own protection,” I repeated. “Protection from what? They’re dead?”

“From the Avatari,” Freeman said.

Hearing Freeman mention the Avatari, I felt a moment of elation. I’d been expecting Freeman to play whatever ace card he’d been hiding, but he didn’t have a card at all. Instead, he had the missing piece of a very frightening puzzle.

The Double Y clones, the rush to get as many ships to Olympus Kri as possible, the way the Unified Authority never pressed the attack …they all fit together in a flash of clarity. The Double Y clones were never meant to destroy our Navy, they were meant to behead its leadership, to kill the officers and leave the ships and crews operational. Once our Navy fell apart, the Unifieds hoped to assimilate the ships and the crews. Clones were designed to follow orders, not to give them. Kill all the leaders, and the followers might well give up without a fight when ordered to surrender. Then what? Then send the ships here? Send the entire Navy to Olympus Kri to … If the Unifieds weren’t planning to attack, why did Freeman want me here? I asked myself, and I knew the answer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Clone Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Clone Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Clone Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.