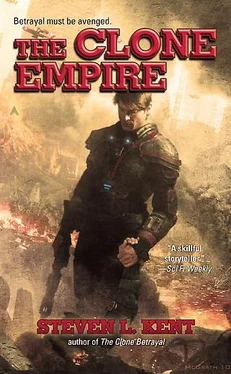

Steven Kent - The Clone Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Kent - The Clone Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Боевая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Clone Empire

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Clone Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Clone Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Clone Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Clone Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It all sounded so good, so victorious. And then I remembered all of the security stations Warshaw had dotting his base.

“If the war is going so well, what’s with all of the security? You’ve got posts at every door.”

“You noticed that?” Warshaw asked.

“And why place your headquarters on Gobi; it’s the shittiest planet in the galaxy.” Until I said those words, I never realized how deeply I resented beginning my career on this planet.

“I didn’t come here for sightseeing,” Warshaw said in a cold, matter-of-fact voice. He waited a moment, then decided that he trusted me, and said, “It’s not the war that’s the problem. It’s the cancer that came with it. We’ve been infiltrated.

“The Unifieds can’t beat us in a fight, so they’re just going to hang back and wait for us to die.”

There were guards and posts right outside Warshaw’s office. There were guards and posts right outside the elevator on Warshaw’s floor. There were guards and posts outside the elevator five floors down, and more guards and posts outside the door of the infirmary. I began to wonder if I would find guards and posts at the opening of the toilet stalls in the officers’ head.

Walking like a man who means business, Warshaw led me through the front of the infirmary into its darker reaches.

“At least this building is secure,” I said, as we stepped into an antiseptic world of plastic sheets, stainless-steel tables, and air that smelled of formaldehyde. Tools both primitive and modern arrayed on chrome-plated trays, coffin-sized tables, laser saws, and bladed scalpels—this part of the infirmary reminded me of a medieval dungeon.

“You would think a place like Gobi Station would be safe,” Warshaw said, starting a new conversation. He waved to a doctor—a short, skinny natural-born in a lab coat. Warshaw asked, “Can you get Admiral Thorne?” and the doctor left the room.

“Thorne? He’s on Gobi?” I asked.

Thorne—Rear Admiral Lawrence Thorne—was a natural-born who had allied himself with the clone cause. He had been the commander of the Scutum-Crux Fleet when Warshaw and I took over. The rest of the natural-borns transferred out, but he stayed on with us.

“Yeah, as of last week,” Warshaw said.

The double doors spread open, and the doctor rolled a gurney into view. Until I saw that gurney, the significance of our surroundings had not occurred to me. We had walked through the infirmary and entered the morgue. We had entered the meat locker.

The man whom I had mistaken for a physician must have been a coroner. He pulled back the sheet, and there was Lawrence Thorne, flat on his back, his hands by his sides, an old man with skin so bleached and wrinkled he might have spent the last twenty years sitting in a bath. His legs were as skinny as a bird’s, but a roll of flab orbited his gut. Seeing Thorne laid out in this butcher shop, I felt a pang of regret.

“What happened to him?” I asked, still staring down at the body. He looked small and frail.

“His neck was broken,” said the coroner.

“How did he break it?” I asked.

“Somebody broke it for him,” Warshaw said. He looked to the coroner for confirmation.

“There’s bruising along the jaw,” the coroner said. Showing the coroner’s familiarity with the dead, he turned Thorne’s head to one side. Along the bottom of his wrinkled cheek, faint bruises showed in bluish ovals. The death tech placed his hand over the bruises, his fingers reaching toward the spot where the jaw met the ear. It wasn’t a perfect fit, but the spread of his fingers matched the angles of the bruises.

I’d killed a man or two using that very technique.

“Can you tell anything about the killer from the bruises? Size? Weight? Anything?” I asked.

Warshaw answered. “Yeah, they tell us something.” He walked to the door and asked one of the guards to join us. Clearly nervous around Admiral Warshaw, the petty officer approached the table.

Warshaw pointed at Thorne’s corpse, specifically at the dead admiral’s jaw, then said, “Put your fingers over the bruises.”

The man hesitated.

“Don’t worry, he won’t bite. This old boy won’t bite anyone ever again.”

The petty officer slowly lowered his hand over Thorne’s cheek. He spread his fingers so that they covered the bruises. It was a perfect fit. He kept his trembling hand on the dead man’s face and turned to look at Warshaw.

“That will do,” Warshaw said.

The hand shot up.

“Go wash up and get back to your post,” Warshaw said.

Still looking shaken, the petty officer said, “Aye, aye, sir,” and left in a hurry.

Warshaw grimaced, and said, “It’s like Cinderella; only this time, everybody’s foot fits the slipper.”

“He was killed by a clone?” I asked.

“Yeah. Doesn’t narrow down the list much, does it?” Warshaw said. “The only ones on this base we can be sure did not do it are you and me. I’m natural-born and you’re a Liberator; our fingers don’t fit.”

The coroner said, “I’m not synthetic.”

Warshaw said, “Yeah, and the good doctor here, he’s natural-born, too.”

Warshaw’s fingers would fit, of course, but I saw no reason to point that out.

“It’s not just Thorne. They killed Lilburn Franks,” Warshaw said. “They got him the same way—broke his neck. One of his lieutenants found him on the floor in his quarters.

“Specking nasty way to go, a broken neck.”

Actually, in the litany of ways to go, a broken neck ranked just below death by sexual exhaustion in my book. Thorne might never have known he was in danger. He might have simply walked around a corner, felt a quick tug, then never felt anything again.

All of the swagger had washed out of Warshaw. He spoke quietly. “They killed three of my top five officers, Harris. Two of them were killed right here, right in this base.

“They hit us even harder a few pay grades down. The Unifieds hit so many officers in the Central Norma Fleet that we had to shut down one of our fighter carriers. We didn’t have enough officers for the chain of command.

“How do you fight back against something like this? It’s like they hit us with a specking ghost. You know what the worst part is? I don’t know what to do about it. It’s like we conquered the whole specking galaxy, and now we’re dying of cancer.”

I did not know what to say.

We left the morgue. Warshaw invited me to have dinner with him, and I told him I needed to rest. My mind was reeling. I had started the day on Terraneau, spent hours sealed in a derelict battleship in the Cygnus Arm, and now I was talking mass murders on Gobi.

Warshaw laughed when I declined his invitation. “Rest? Harris, I’m about to paint a specking target on your back, and you want a nap? I haven’t even begun your briefing.”

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Warshaw gave me a couple of hours to rest before dinner.

I had a tiny billet, not much more than a rack and a head, with a writing desk that folded out of the wall. I went to the head, shaved and showered, and used the Blue-Light to laser clean my teeth. And then I crawled onto my rack, not to rest, but to think.

The “Enlisted Man’s Empire”—that was what we called ourselves now that they had twenty-three planets and thirteen fleets. None of that conquest would have been possible had Warshaw not created his own miniature version of the Broadcast Network. The Unified Authority had built broadcast stations near each of its planets, now Warshaw was using them to link our planets together. He’d built his own pangalactic superhighway using the ruins of another empire.

He could even reach Earth. In fact, reaching Earth would be easy. Any of our broadcast stations could be rigged to send ships there. Getting back would be another story. The Mogats had destroyed the Mars broadcast station, the station that used to broadcast ships out of the Sol System. Without the Mars Station, any ships we broadcasted into Earth space would be stuck there.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Clone Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Clone Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Clone Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.