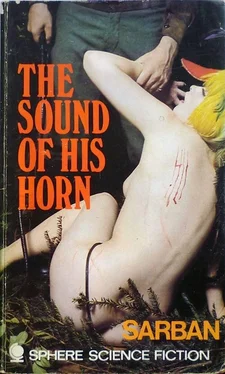

Сарбан - The Sound of His Horn

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Сарбан - The Sound of His Horn» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Альтернативная история, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sound of His Horn

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sound of His Horn: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sound of His Horn»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sound of His Horn — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sound of His Horn», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Such little things impress you. They are such convincing evidence of a highly developed industry, of abundant material wealth which enables people to keep all their domestic equipment new and perfect. The Germans, of course, had a reputation in industrial chemistry, in plastics and synthetic fabrics, and so on, but it was disconcerting to find such things so abundant in civilian life after nearly four years of war.

The furniture and the floor of the room, at any rate, were not made from coal-tar or milk or wood-pulp– but of natural wood with the beauty and variety of the forest in their grain. The timber had been chosen and worked by people who loved it. I began to feel I knew something of the character of the owner of this place of Hackelnberg. He was rich, obviously; perhaps an old Junker or one of the princes of the old Empire whom the Nazis found it politic to leave alone; one who was not only able to buy the best products of the factories, but who also had the taste to combine them with the best of country craftsmanship using woodland materials. He would be a lover of forest things.

Well, all that, you may say, was as much fancy as deduction. Sherlock Holmes, no doubt, would have done much better with the data provided by one room and three people, but I flatter myself that the broad lines were pretty accurate.

I had my first positive confirmation from the source where I least looked for it: from Night Nurse, to whom I scarcely spoke more than to say good evening or good morning. But it was an odd thing that got it out of her.

I have mentioned that the extraordinary quietness of the place was one of the things that formed the basis of my reasonings. It fitted the other explanation, too, of course: that I was a guest, a prisoner-guest if you like, in a country house. The property was obviously a large one. How large, I had no idea, for even when, in the nurses' absence, I crept out of bed to the window, I could see no distance at all: the trees just outside were too tall and their foliage too thick to give me any view except of their own green complexity. There was, however, no noise of traffic, not even the most distant sound of a car horn or an engine whistle. I did not even hear an aeroplane, and that, in Germany in 1943, struck me as peculiar. True enough, the Third Reich at the point of expansion it had then reached was a much wider land than England; airfields would not necessarily be so thick on the ground in Eastern Germany as they were at that time in East Anglia, for example. And I supposed Hackelnberg was far enough east to be out of range of our own bombers; there was certainly no black-out curtain in my room, no precautions about showing lights were ever taken, and you could never have suspected from anything in the nurses' conversation that they so much as knew that Germany was at war. That was deliberate, of course: part of the business of nursing me and avoiding topics that might excite me. Whenever I mentioned the war Day Nurse pretended a complete misunderstanding of what I was saying, told me I was not to bother my head with old past things and tried to interest me in the flowers.

Then about a week after this full awakening of mine I began to hear things. My hands were almost completely healed and I was perfectly well in myself. I wanted to get up; lying in bed all day began to bore me. The result was that I no longer slept soundly all night.

At first I thought the sounds were dream-sounds, for I heard them in a doze, slept again and only recollected them in the morning. They were such remote, isolated sounds, so unconnected with the restricted life going on round me. They were notes of a horn, sounded at long intervals, each one as lonely in the pitch dark and utter silence, as one single sail on a wide sea. I've heard bugles in the dark and loneliness of the sea and I've heard an English huntsman's horn, and I know how sometimes their music can tighten like a hand-grip on your heart. But these notes were different. I could not picture the scene where they were being sounded, I could only feel the profound melancholy, the wildness and strangeness of them; they spoke through the dullness of my half-sleep with a most desolating sorrow and pain.

I remembered their sadness long into the cheerful day, and I found myself listening for them the next night, wide awake in the dark, waiting for them, yet hoping I should not hear them.

One night I heard them before ever I had gone to sleep. There could be no question of a dream then. It was a light night with the moon near full and only a few small islands of white cloud. I slipped out of bed and listened at the open window. There was some wind and that played with the horn notes, lifting them to me one moment, then changing and bearing them far away; that surging and dying seemed to give their music a different quality this night The sadness and pain were still there, but the wildness was dominant; the horn seemed to be roving about the woods, beating back and forth, questing, calling, sometimes with a stirring fierceness, sometimes with the long, withdrawing note of failure.

The night was full of noises. The forest was as restless as the ocean. The wind stirred the beeches outside my window; the trees conversed in a multitude of tongues; a whole woodland orchestra was playing, with the horn leading. I could fancy all sorts of voices and instruments within that wild discourse; imagination could turn the whine of swaying branches into the whimper of hounds and the sudden loud shuddering rustle of leaves in a gust could be the racing patter of their feet. I leaned there a long time, listening, intent on the horn above all the other sounds, and I felt a strange disturbance of spirits increasing within me; it was not the sadness the horn had induced in me before, but a nervousness, an apprehension–that enfeebling sense of danger you may have sometimes before you have realised from what quarter, by what weapon you are threatened.

I listened until the horn had died far away and my ear could no longer distinguish it above the soughing and sighing of the uneasy trees, then I crept back into bed and lay for a long time, looking at the moon-lit square of my window, listening still for the notes to sound again, but at length I fell asleep.

Before it was well light I was out of bed again, torn suddenly from sleep by the horn very loud and close. The wind had fallen now, the moon had set; the morning was quiet and grey; and then I heard the loud horn ringing arrogantly through the grave twilight of the dawn. The note of triumph was insistent. I leaned out and tried to pierce the screen of trees with my vision; the oft-repeated blasts were passing through the woods not far from my window, passing away to somewhere beyond my room to the right.

Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of a white form gliding through the dusk of my room and I gave a great start of fright before I recognised Night Nurse.

«Go back to bed!» she whispered, making the low, urgent tone sound more peremptory than any I had heard her use before. She moved between me and the window and stood with her back to the opening, as though to prevent me throwing myself out, and all the time I could see that she was listening intently to those prancing, exultant notes of the horn, diminishing now as they passed on through the forest.

«What is it?» I asked, when I had obeyed her and covered myself with the sheet again. Utterly unexpectedly she gave me a straight, serious answer:

«It is the Count coming home.»

It was a true answer, I was certain; she had forgotten for the moment that I was her patient and had let slip into her voice an expression of just that vague alarm that I myself had felt when listening to the horn the night before.

«The Count?» I asked. «Who is the Count?» She came and looked down at me, so that I could just make out her features in the grey light from the window.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

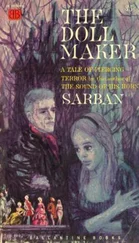

Похожие книги на «The Sound of His Horn»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sound of His Horn» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sound of His Horn» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.