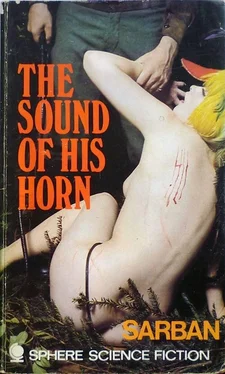

Сарбан - The Sound of His Horn

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Сарбан - The Sound of His Horn» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Альтернативная история, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sound of His Horn

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sound of His Horn: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sound of His Horn»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sound of His Horn — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sound of His Horn», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

«My dear fellow,» he answered, and something jarred on me in the glib way he brought the phrase out in his German accent, «my dear fellow, I don't think you're insane at all. Not that I should care much if you were. Your case interested me physiologically. You were affected by Bohlen Rays. They are usually fatal, but you have responded to my treatment. I am pleased with you. From my point of view you are cured, you need only a little time and some exercise to recover the use of your muscles completely.»

«But you think I'm unbalanced,» I insisted. «Even though you're not interested, you're a doctor; you know when a person's mad. Am I?» He looked out of the window and drew down the corners of his mouth, seeming to find my question irrelevant or impossible to answer. Then in a bored, offhand way, he said:

«There's bound to be some cerebral disturbance. A temporary amnesia would be normal and some kind of delusions could be expected. In your case it seems to take the form of believing that you are living in a former period of history. I suppose you have read a good deal of history, about the War of German Rights and so forth, haven't you?»

«History?» I said, bewildered. «Yes....»

He interrupted me airily.

«I should not worry. It will pass.» He looked at me with very much the same indolent appreciation in his eyes as when he had surveyed Day Nurse, interested in nothing but my physical state. «What does it matter if it doesn't?» he asked. «You have the use of your body again. I don't know that you'll find anyone particularly interested in your mind here.»

Even though I had by now seen through the sham geniality of his first manner, the brutality of this remark astonished me. Puzzled and alarmed though I was at what he said about my delusion, I was convinced in my own mind that I was sane and I determined to meet his brutality with composure.

«I'm not so conceited, Doctor, as to imagine that my mind is of much interest to anybody but myself,» I said. «But I should like to thank you for taking such very good care of my body; it feels quite well now and I think my only worry is what you intend to do with it now you've repaired it. Am I to be treated as a prisoner of war, or not?»

He put his elbows on the desk, propped his chin on his folded hands and arched his brows, looking at me with a certain disquieting relish.

«You know, I like you,» he said. «I find your conversation refreshing. Besides, I think you are probably a good listener and it will be excellent for me to practice my English a little. I have no idea what the Graf intends to do with you, but in my own little hospital here I am Der Fuehrer–and in case your period doesn't come as far up to modern times as that, that means God–and as I like your company I shall keep you here as long as possible. You have no idea how depressing it is for a solitary intellectual surrounded entirely by sportsmen and slaves. I am sure you will stimulate me to make a great many observations about this establishment, and luckily your–er–infirmity will enable me to express them with comparative safety. You may keep your room until I need it for another casualty, but I beg that you will honour my own table. I shall try to show you something of the estate as opportunity offers, but I must warn you against going out by yourself, particularly at night. It would grieve me very much to have my first real success with the anti-Bohlen Ray treatment un-professionally dissected by the Graf's hounds or those other creatures that he keeps.»

He rose, and coming swiftly round clapped me on the shoulder, grinning down at me.

«So, Herr Lieutenant, accept the fortune of war like a soldier of those old heroic times you live in, and share a piece of venison and a bottle of Bordeaux with your enemy at half-past twelve precisely. Ach, though!» he exclaimed. «I must get you something to wear. Your own clothes have gone to the incinerator, I believe.»

He bent and spoke softly into a small apparatus on his desk. While he was occupied I got up and looked at the fine electric clock on the bookcase to which he had pointed when he invited me to lunch. It was a handsome instrument, comprising not only a clock but a thermometer and barometer, and it exhibited certain additional figures in small illuminated apertures which I did not at once understand. Then, I saw that one combination must give the day of the month. It was evidently the twenty-seventh of July. But under this was the isolated figure '102.'

The Doctor came across while I was peering at this.

«So,» he said. «You admire my chronometer? As an officer of the old-time Navy that should interest you. But what puzzles you about it?»

I pointed to the small figure '102.'

«Ach, ja,» he said. «The year also. Hardly necessary, one would have thought.»

«The year?» I repeated, staring at him.

He threw back his head and laughed aloud, then apologised with exaggerated courtliness.

«Alas, it is so difficult to be consistent when two people are living in different centuries at the same time. Forgive me, I should explain that I–solely for purposes of practical convenience, of course–subscribe to the convention that we are living in the hundred and second year of the First German Millenium as fixed by our First Fuehrer and Immortal Spirit of Germanism, Adolf Hitler.»

5

It amazes me now that I preserved so unruffled a faith in my own sanity all the time I was at Hackelnberg. Perhaps I did it by achieving a kind of suspension of judgment: I was in a set of curious circumstances for which I could find no immediate and satisfying explanation, but there must be an explanation and I felt I should eventually arrive at it by patient observation and reasoning. I felt an immense patience in myself. Perhaps that was a legacy of the prison camp; you can't plan and execute a tunnelling project without having or acquiring patience. Still, it is surprising how easy I found it to leave this whole matter of chronology in abeyance. The Doctor believed he was living a hundred years after the war, I believed I was living in it: time would show which of us was right. Time, yes, and space too. If I could go about a bit and see the other people at Hackelnberg, I felt I should soon know one way or the other.

Yet, of course, I reasoned from my inner conviction, even supposing the Doctor was right, that would not prove that I was mad. The Doctor thought I was suffering from some harmless delusion, but there would be another possible explanation: might not my unconsciousness have covered a century of time? Might I not have slept in the forest now called Hackelnberg for a hundred years like Rip Van Winkle in the Catskills?

Well, you'll probably say there was no doubt about my state of mind if I could consider such an explanation seriously. But what is a man to think when he feels so well, so balanced, so sane, and above all, when his senses are working so perfectly and he is taking such a lively interest in everything round him? Never in my life had I been so intent on observing and memorising everything I saw. I tell you, my memories of what I saw at Hackelnberg, what I felt and did there, are more vivid and real to me than anything else in my whole life.

It was all so real, and–though it's a queer thing to say, seeing what happened–so interesting.

I don't mean that all the discoveries were pleasant. They were not by any means. In fact, they would have appalled me if I had kept leaping back and forth across the time-gap, as it were, to look at them with the eyes of 1943. But I didn't do that. I accepted the apparent history of the last hundred years as known to Hackelnberg, and later, escape meant not escape in time, but escape in space. The problem was to get across that fence of rays again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

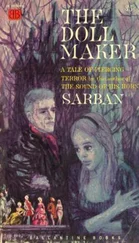

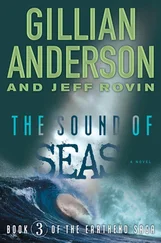

Похожие книги на «The Sound of His Horn»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sound of His Horn» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sound of His Horn» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.