The men on the ground cheered, and Eugenia — quite unlike herself — clapped. The rising wind got hold of the ship and pulled it over the factory, toward the narrow strip of the forest, until its golden glow was hidden from view behind the treetops. The sun had sunk below the horizon, and Eugenia took my arm.

“Let us return to the hotel, Sasha,” she told me. “There won’t be anything else exciting here today.”

The next day, at breakfast, we heard the innkeeper talking about a fire ball crashing in the fields just outside of town and the peat fires that started last night just a few miles to the west. Neither Aunt Eugenia nor I mentioned the airship and its fate to my mother.

It took us four days of being shaken along the ruts and staying in inns before we arrived at the severe glory of the capital. Eugenia had arranged for the hiring of staff who had uncovered furniture, cleaned, provisioned the place, and laid fires to warm the house in anticipation of our arrival, but it took another day of unpacking and arranging before we were settled in our St. Petersburg quarters. It took even longer before I was allowed to go for a walk along the Neva’s embankment.

Oh, but the wait only made it more rewarding — as I strolled across the drizzle-slicked stones of the embankment, a sense of historical gravitas washed over me: these were the stones my papa’s feet walked over, and the emperor’s, and Peter the Great’s; every important person who had ever lived in this city, every prominent player in the tragedies of our national life had left invisible footprints here.

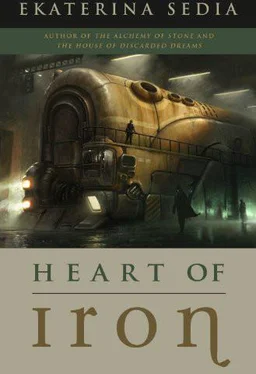

I looked at the slick surface of the river and noticed it churn, water frothing white and green as bottle glass until a heavy brass hull, patina-covered, breached the surface. It looked like a monstrous sinking boat that was going the wrong way. A pair of binoculars mounted on a long pole swiveled toward me, and almost immediately the round cover on the convex back of the boat started turning. A few passersby stopped and clustered closer to the water, pointing and gasping. I had to push through the small crowd to get a view of the goings on.

When it opened, a very ordinary-looking freedman, dressed in linen shirt and matching trousers girded with a piece of rope, stepped out of the hatch just as I managed to work my way to the front of the crowd, inches away from the gray stone wall and the black water lapping at it.

“How do you do, miss,” the freedman said to me. He then proceeded to walk the length of the monstrous contraption to adjust one of the mismatched knobs studding its tail end like a lace-maker’s bobbins. He fiddled with one knob and then another one, as I watched in mute fascination, until he returned to the hatch and climbed inside. The green brass shuddered and several of the bobbins exhaled white clouds of steam. The water hissed and bubbled as it lapped against the knobs, and the boat soon sunk under the water and disappeared from view, leaving only a short-lived white-crested wave in its wake.

Afterwards, I walked along the Nevsky Prospect, the heart of the city laid out so vast, flayed open for the Kazan Cathedral and its square, and I gawped at the rearing horses guarding the Anichkov Bridge. Then I stopped to look at the stately, simple lines of Beloselsky-Belozersky Palace. I tried to guess what silent and luxurious life teemed behind those tall vaulted windows of the second story, who were the shadows sliding past the lacy white curtains like fishes under ice.

I could lose myself in these streets, and even as the rain grew heavier I dawdled, reluctant to go back to our quarters by the Moyka River, not too far from the Yusupov Palace. I had decided to go to St. Isaac’s Cathedral and the Senate Square tomorrow; no doubt, both my mother and Aunt Eugenia would be interested in visiting the place of Papa’s triumph.

However, upon my return I learned that Eugenia had other plans. Normally my mother and my aunt would arrange for an audience with the emperor, but because of my impending debut and associated emergencies — a tear in one of my silk slippers, a length of soutache coming undone along the front of the dress — they had been unable to arrange for an audience before the ball. The ball at the Winter Palace was two days hence, and preparations had to be made. My aunt was still overseeing getting the apartment and menus in order, and all other business had to wait until after the ball.

The hired maid turned out to be handy with a sewing needle, and thanks to her the clothing emergencies were solved with just a modicum of anxiety, letting us all fret about other matters. I was mostly worried about meeting my peers — even though Miss Chartwell did her best to impart the necessary knowledge of English (no one spoke Russian at the court since Emperor Constantine contracted a profound case of Anglophilia) and manners, I was still more used to the company of peasant and engineer children. I suspected that the young ladies of my own age and social standing would have a much less interest in the life of our estate than I did. Even my treasures, the books by James Fenimore Cooper, were unlikely to interest them.

Meanwhile, my mother seemed to grow even more despondent, the present receding as the deluge of memories of the house and familiar sights of the capital assaulted her. She mopped at her eyes with her handkerchief and drifted from one well-lit room to the next, pausing only in front of the wide bay windows to catch a glimpse of the pavement’s rain-slicked stones and the gleaming of St. Isaac’s across the river.

Aunt Eugenia was also lost in thought — she had retreated to her room and muttered darkly there, pacing all the while. I suspected that her discontent had to do more with the present state of affairs rather than the memories of the past youth. She seemed to be embroiled in preparations for the ball — her dress of black silk, decorated with charcoal-gray diamonds sewn onto a ribbon that ran all the way down the front was both beautiful and severe — much more elaborate than her usual clothing, and I was flattered that she would go to such length for me.

As it turned out, it wasn’t my debut Aunt Eugenia was preparing for.

The day of the ball was gloomy, but it mattered little as all of society headed for the Winter Palace. The Neva swelled with rain and turned leaden like a corpse, and small white-crested waves lapped at the mottled walls of the embankment. The squares and throughways were choked with the multitude of carriages and horses, and for a while I thought we might never arrive to the palace — I blushed when I realized the thought filled me with relief. I tried hard not to pick at the length of soutache twisting and winding down the front of my dress, and instead played with lace rosettes along my neckline and worried at the buttons of my long gloves.

My mother kept looking at the torrents of rain outside the window, and Aunt Eugenia frowned at her private thoughts. In her black and gray, she was formidable — and a stunning contrast to my mother who wore youthful dark rose and an overabundance of lace and ribbons. Between the three of us, she was dressed most as a debutante.

But, to my disappointment, we somehow managed to arrive at the palace and ascended its grand staircase, chandeliers blazing over the crowd — bright dresses and dark suits, with the occasional royal blue of officers’ uniforms and the white of pelisses. There were bare shoulders and enough lace to wrap the Earth three times over. There was an overabundance of glossy marble, too much light and sparkling jewels. My head spun. If not for the strong, dry hand of my aunt steadying me, I would have lost my footing and tumbled gracelessly down the marble staircase. We entered the ballroom arm in arm — or rather with me leaning on her strong, square hand, her surprisingly small birdlike bones belying her evidently supernatural power.

Читать дальше