Landsman feels it then. A hand laid on his, two degrees warmer than normal. A quickening, an unfurling like a banner in his thoughts. Before and after. The touch of Mendel Shpilman, moist, electric, conveying some kind of strange blessing on Landsman. And then nothing but the cold air of Bina Gelbfish’s childhood bedroom. The flowering O’Keeffe vagina on the wall. The stuffed Shnapish sagging on a bookshelf beside Bina’s wristwatch and her cigarettes. And Bina, sitting up in bed, propped on an elbow, watching him, sort of the way she watched those kids go after that hapless penguin pinata.

“You still do that humming thing,” she says. “When you’re thinking. Like Oscar Peterson, only with no piano.”

“Fuck,” Landsman says.

“What, Meyer?”

“Bina!” It’s Guryeh Gelbfish, that old whistling marmot, from across the hall. An ancient terror momentarily seizes Landsman. “Who is there with you?”

“Nobody, Pa, go to sleep!” Again she says, in a low whisper, “Meyer, what?”

Landsman sits down on the edge of the bed. Before; after. The exaltation of understanding; then understanding’s bottomless regret.

“I know what kind of a gun killed Mendel Shpilman,” he says.

“All right,” Bina says.

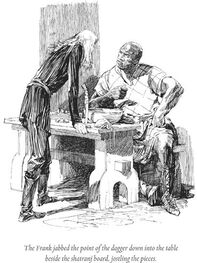

“It wasn’t a chess game,” Landsman says after a moment. “On the board in Shpilman’s room. It was a problem. It seems obvious now, I should have seen it, the setup was so freaky. Somebody came to see Shpilman that night, and Shpilman posed him a problem. A tricky one.” He moves the pieces of the pocket chess set, his grasp of them sure, his hand steady. “White is all set up to promote his pawn, see. And he wants to promote it to a knight. That’s called underpromotion, because usually, you want to get yourself a queen. With a knight here, he has three different ways to mate, he thinks. But that’s a mistake, because it leaves Black-that was Mendel-with a way to drag the game out. If you’re White, you have to ignore the obvious thing. Just make a dull move with the bishop, here at c2. You don’t even notice it at first. But after you make it, every move Black has leads directly to a mate. He can’t move without finishing himself. He has no good moves.”

“No good moves,” Bina says.

“They call that Zugzwang,” Landsman says. “‘Forced to move.’ It means Black would be better off if he could just pass.”

“But you aren’t allowed to pass, are you? You have to do something, don’t you?”

“Yes, you do,” Landsman says. “Even when you know it’s only going to lead to you getting checkmated.”

Landsman can see it starting to mean something to her, not as evidence or proof or a chess problem, but as part of the story of a crime. A crime committed against a man who found himself left with no good moves at all.

“How’d you do that?” she says, unable to suppress completely a mild astonishment at this evidence of mental fitness on his part. “How’d you get the solution?”

“I saw it, actually,” Landsman says. “But at the time I didn’t know I was seeing it. It was an ‘after’ picture-the wrong picture, actually-to the ‘before’ picture in Shpilman’s room. A board where White had three knights. Only chess sets don’t come with three White knights. So sometimes you have to use something else to stand in for the piece you don’t have.”

“Like a penny? Or a bullet?”

“Any kind of thing a man might have in his pocket,” Landsman says. “Say a Vicks inhaler.”

The reason you never developed at chess, Meyerle, is because you don’t hate to lose badly enough.”

Hertz Shemets, sprung from the hospital with a nasty flesh wound and that Sitka General smell on him of onion broth and wintergreen soap, is lying on the couch in his son’s living room, his thin shanks sticking out of his pajamas like two uncooked noodles. Ester-Malke has a ticket for Berko’s big leather armchair, with Bina and Landsman in the cheap seats, a folding stool and the armchair’s leather ottoman. Ester-Malke looks sleepy and confused, hunkered down in her bathrobe, her left hand fiddling with something in the pocket that Landsman figures for last week’s pregnancy test. Bina’s shirt is untucked, and her hair is a mess; the effect partakes of shrubbery, some kind of ornamental hedge. Landsman’s face in the pier glass on the wall is an impasto of shadows and scurf. Only Berko Shemets could look sharp at this little hour of the morning, perched on the coffee table by the couch, clad in a pair of rhinoceros-gray pajamas, neatly creased and cuffed, his initials worked over the pocket in mouse-gray crewel. Hair combed, cheeks eternally innocent of whisker or blade.

“I actually prefer losing,” Landsman says. “To be honest. I start winning, I get suspicious.”

“I hate it. Most of all I hated losing to your father.” Uncle Hertz’s voice is a bitter croak, the voice of his own great-aunt calling out from beyond the grave or the Vistula. He’s thirsty, tired, rueful, and in pain, having refused any medication stronger than aspirin. The inside of his head has got to be ringing like the slammed hood of a car. “But losing to Alter Litvak. That was almost as bad.”

Uncle Hertz’s eyelids flutter, then settle over his eyes. Bina claps her hands, one-two, and the eyes snap open.

“Talk, Hertz,” Bina says. “Before you get tired or go into a coma or something. You knew Shpilman.”

“Yes,” Hertz says. His bruised eyelids have the veined luster of purple quartz or the wing of a butterfly. “I knew him.”

“You met him how? At the Einstein?”

He starts to nod, then tilts his head to one side, changing his mind. “I met him when he was a boy. But I didn’t recognize him. When I saw him again. He had changed too much. He was a fat little boy. Not a fat man. Thin. A junkie. He started coming around the Einstein, hustling chess for drug money. I would see him there. Frank. He wasn’t the usual patzer. From time to time, I don’t know, I would lose five, ten dollars to him.”

“Did you hate that?” Ester-Malke says, and though she knows nothing about Shpilman at all, she seems to have anticipated or guessed at his answer.

“No,” her father-in-law says. “Strangely, I didn’t mind.”

“You liked him.”

“I don’t like anybody, Ester-Malke.”

Hertz licks his lips, looking pained, sticking out his tongue. Berko gets out of the chair and takes a plastic tumbler from the coffee table. He holds it to his father’s lips, and the ice jingles in the tumbler. He helps Hertz to drain half of it without spilling. Hertz doesn’t thank him. He lies there for a long time. You can hear the water sluicing through him.

“Last Thursday,” Bina says. She snaps her fingers. “Come on. You went to his room. At the Zamenhof.”

“I went to his room. He invited me. He asked me to bring Melekh Gaystik’s gun. He wanted to see it. I don’t know how he knew I had it, I never told him. He seemed to know a lot about me that I never told him. And he told me the story. How Litvak was pressing him to play the Tzaddik again, to rope in the black hats. How he’d been hiding from Litvak, but he tired of hiding. He had been hiding his whole life. So he let Litvak find him again, but he regretted it right away. He didn’t know what to do. He didn’t want to keep using. He didn’t want to stop. He didn’t want to be what he wasn’t, he didn’t know how to be what he was. So he asked me if I would help him.”

“Help him how?” Bina says.

Hertz purses his lips, gives a shrug, and his gaze sidles toward a dark corner of the room. He is nearly eighty years old, and before this he has never confessed to anything.

“He showed me that damned problem of his, the mate in two,” Hertz says. “He said he got it off some Russian. He said if I solved it, then I would understand how he felt.”

Читать дальше