“We must send the Armenian Fox some more troops. Draw up a list of units we can release for his use.”

Malinin raised an eyebrow at his superior, knowing he was husbanding his reserve forces for the right moment.

By way of reply, Zhukov adopted a conspiratorial tone to lighten the moment, but he didn’t carry it off.

“Just enough to shut him up, Comrade. Just enough to shut him up, and not a soldier more.”

Malinin looked at his commander, realising for the first time that the strain of command was laying heavier than normal on his shoulders.

1957hrs, Friday 7th September 1945, Junction of Routes 317 & 323, East of Unterankenreute, Germany.

The 4th Indian Division had given up Bergatreute and Wolfegg under pressure, dropping back into the woods to the west, protecting the major highways that led to the remaining parts of South-Western Germany still under Allied control.

They had yet to take serious casualties, their retreat caused by logistical problems that saw some frontline units without more than a few minutes worth of ammunition.

Food was also just beginning to become an issue, the restrictions of their faiths meant that it was less easy to scavenge or accept gifts from the friendly population.

A serious enemy thrust on Vogt had been bloodied and repulsed, the combination of British tanks, Indian artillery, and USAAF ground attack proving too much for a large mechanized force that withdrew in disarray.

Those units melting into the cool shadows of the trees found ample munitions and hard supplies waiting, product of a magnificent effort by the Division’s logistical chain, meaning that this was a line that they could hold.

Bullets and explosive had taken priority over bread and meat, so only modest amounts of food reached some units, whilst others waited in vain. Many men went hungry that evening, partially because there was nothing to eat, and partially because of the presence of the enemy.

They were known as the ‘Red Eagles’, a homage to their divisional badge.

Their service during the Second World War was exemplary, from the 1940 campaigns in the Western Desert, through East Africa and the rout of the larger Italian Forces, Syria and finally Italy, where the division earned undying glory in and around the bloodbath that was Monte Cassino.

The 4th was considered an elite formation, but it had taken heavy casualties in the process of acquiring its illustrious reputation.

Returned from a stint of armed policing in Greece, the 4th Indian Division had slotted back into the Allied order of battle alongside sister units with whom they had shared the excesses of combat, only to be swiftly transferred north and into the cauldron of the new German war.

It performed well against the new enemy, and swiftly relieved the exhausted 101st Airborne.

The new positions assigned to the 7th Indian infantry Brigade covered the routes out of Wolfegg, and the approaches to Vogt.

The 4th/16th Punjab Regiment, ably supported by two platoons of the 6th Rajputana MG Battalion, had stood firm in and around Vogt, British tanks from the 26th Armoured Brigade causing heavy casualties amongst the attacking T-34’s.

As the Soviet probes continued, the 2nd/11th Sikhs were pushed hard along their defensive line, set in parallel with Route 324 to the north of Vogt.

On Route 314 to the north, British soldiers of the 1st Royal Sussex Regiment folded back, but did not give, forcing the attacking Soviet infantry and cavalry to retreat, leaving scores of dead on the field.

An unusual error in Soviet attack scheduling had delayed the central assault, enabling the defending artillery to concentrate on assisting the Sussex Regiment before switching to the aid of the forces defending Routes 317 and 323.

2007hrs, Friday 7th September 1945, astride Altdorfer Strasse [Route 323], 2 kilometres south-west of Wolfegg, Germany.

Company Havildar Major Dhankumar Gurung looked around him, able to make out the shape of one of his men here, a weapon ready and manned there.

8th Platoon was quiet, safely hidden behind their tree trunks, protected by the hastily scraped foxholes, or comfortable in the old German trench.

Not one man had suffered any injury as the Soviet artillery, weak by comparison to normal, had probed the defensive positions of the Sirmoor Rifles.

Part of their line was a trench dug months before their arrival, eight foot deep, wood reinforced and with firing steps along its length, a relic of the previous conflict.

Gurung’s soldiers had extended the trench, and taken advantage of natural depressions in the ground, as well as fallen tree trunks, creating a strong position from which to resist.

Thus far, the battalion had not seen an enemy, apart from the occasional flash of an aircraft overhead.

According to the legends of the British Army, no enemy relished fighting these wiry hillmen from Nepal, and, to a man, they were keen to get to close quarters with the new foe to put their marshall skills to the test against a strong and cunning enemy.

The Sirmoor Rifles, also known as the 1st/2nd [King Edward VII’s Own] Gurkha Rifles, waited in anticipation of the battle to come.

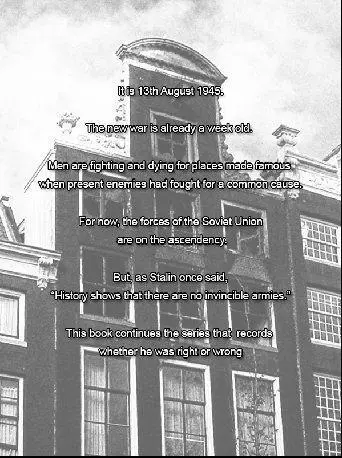

[Book Three of the Red Gambit series, ‘Stalemate’, should be available by January 2013 on Amazon Kindle as a download, and createspace.com as a book.]

Fig #50 – Rear cover graphic

561