Will Celano’s meetings return as quickly, though. One fears there may be a point where the destruction of property, vicious as it is, is not quite the end of it. Why should that barrier remain unbreached? On all sides, actually, the tumult, this thousand-sided Möbius strip of a conflict, has remained below this threshold. What does it say about the operative forces here that it has? Perhaps we are meant to think there are limits.

Celano’s position has always been obscure. Sometimes it appears to be simply about mobilizing votes. Sometimes there is a sense that something greater is at stake, and it is this that has made things more complicated. But there is something unstateable about the position. It seems to require the provision of a language that is either dead or unborn.

Certainly it is not a classical socialism. Is it possibly antidemocratic even? Does it require a silencing of the reigning masters? Or is it rather a call for a different form, a more perfect vehicle for our original national principles? Some of his essays, attributed and not, suggest this. But welding these arguments together, the strategies they recommend, seems impossible. The elements will not jell, not yet anyway.

Are they, though, meant to lie discretely, as a series of piecemeal, even inconsistent interventions in our political life? Can justice really be schizophrenic in this way? Or is that a characterization from a point of view he wants to explode? Even still: can justice be a disruption? Can it exist as a kind of negation? Or is that only a clearing of a space, a prelude to something more well formed?

It is just this disunity of approach, together with his capacity to effect certain sorts of change, indeed massive change, through his diffuse allies, that makes it possible to impute such an array of motives and actions to Celano, and impossible to cross his name off any list. He can apparently explain almost any eventuality, micro or macro. The Wintry too has a varied program, but then, we aren’t articulating or defending any single position, though many claim the opposite. In any case, haziness, I hope, is not a basic quality of anything we do.

But the ease with which Celano can be invoked, it has made him less predictable, not more. Is that, finally, what he is after? A blurring?

So, the museum: on its surface, yes, the building, the Wintry gathering, can seem natural objects of his animus. Targets. Given that his own meeting ground was destroyed just prior, motives line up nicely. Or they can seem to. That’s the trouble. It depends on which pronouncements of his we take most seriously: the ones about the corrosive social properties of wealth, say, or the ones about its capacity to emancipate, in which case, we are not opposed.

Firm conclusions, then, aren’t possible, not unless and until his doctrine jells. This is a recipe for self-implication, martyrdom even, of a certain sort. I’m sometimes of the mind that he owes it to his followers, and to the broader collective, to make his views cohere; and other times of the mind that, so long as he is listening carefully, and is cautious about making assumptions of the other actors, especially the ones that are nearest to hand, that he might more effectively maintain a certain kind of public scrutiny, that he might sharpen all of our eyes, by remaining in the shadows. Sometimes it is the veil that keeps the attention where one wants it, and where, I agree, it is needed.

I hope, personally, that he does not, and never did, assume the destruction of his hall, Jenko’s hall, must somehow issue from wealth — private wealth, anyway (the state is another matter). In fact, as I say, I hope to find that he sees no necessary moral divide between his causes and the notions we proposed that night.

We must wait, I suppose, for events to unfold.

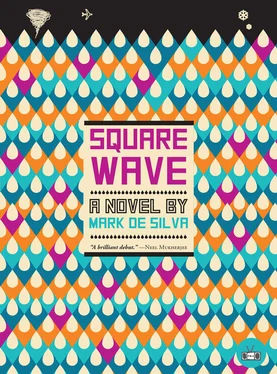

Stagg replaced the magazine within a rectangle of clear floor. All around his desk, the ground was covered in papers, set at odd angles, but never more than one or two layers thick. He’d put the first documents down with no regard, hurriedly tossing them onto any empty area while he carried on with his research. But as their number grew and space contracted, the articles and legal pads and printouts had to be wedged between what was already in place there. Sometimes this wasn’t enough, and to make room, papers would have to be resettled, like people, shunted to one side or the other, or pushed up against others.

Sometimes even this wasn’t enough, and he was forced to layer, offsetting the top document from the one beneath, like a pair of cards. That way, everything remained surveyable from the point from which his work radiated: his old chair.

Squat and hard-backed, extracted from his childhood home — he’d not thought of the place, out in L.A., since it had been sold off, almost fifteen years ago now — he’d done all his grade-school homework in this chair. It seemed the homework never finished.

Stagg leaned back and felt the chair cradle him. In the present apartment, with the present desk, it came up short — it was in no sense adjustable — leaving him to type upward, with his hands held out across from his chest rather than his stomach. Once he’d thought to get a lower-set desk; but then, it had come with the apartment, and it was attached to the bookcase.

Getting a taller chair would have been simpler. But the over-constructed original, made of too many planks, had decayed unrepeatably. It was something he’d never been able to replicate. The weakening of its joints, the legs and back, the wood itself: the chair seemed never to resist him, compensating for the tiniest shift of weight or pressure with a bend or a twist.

At first, the pliancy made him feel as though the chair would collapse beneath him. But it had remained that way for at least a decade now, perpetually on the brink. Somehow this was its most stable state, and what he’d first apprehended as weakness proved instead to be a kind of peculiar responsiveness.

Responsiveness to him, anyway. The proportions of anyone else’s body might destroy it. Sometimes he put clothes on it to discourage Renna from using it. Sometimes she sat on top of the clothes. Other times she would sit on top of him while he was in it, and they would both feel sure they would collapse in a pile of wood. It never worried her. He’d shoo her away then with a smile, or lift her up and set her on the bed.

He leaned back still further in the chair and wondered where she was. He hadn’t seen her for a couple of days now, since that night at Larent’s, with Ravan, where they’d all given up their minds to various substances. He’d taken her home in a cab and she slept all the way. He woke in the morning and she was somewhere else already. She’d texted a few times since then as she scampered around town, working, schmoozing. He’d dutifully responded. But she’d said nothing concrete about meeting and he wasn’t going to be the one to do it again.

The only woman he should have been calling was Jen. In some ways she might need him more than Renna. Anyway it was his job to follow up. He wondered where she was now, and what exactly she was doing, or what Roman she was reading. Lucretius maybe. It’s what he was reading. He still had nothing to tell her, really, so he’d wait until he did.

He let the front legs of the chair come down and opened his eyes. Now that he had it here with him, he found it hard to work, or rather to think, without it. His most probing ruminations seemed to occur in its arms, leaning back away from the desk, with his eyes falling on an empty wall.

It was the only furniture that felt necessary. A duvet on the floor could suffice, and his computer was a laptop. It would be easier to bring everything else in the room in line with the chair than the reverse.

Ultimately, though, he changed nothing. The comfort that was good for thinking was not, it turned out, good for writing. Between the chair and the desk there was a useful mismatch. The slight but continuous strain it caused brought Stagg a greater consciousness of the act of writing, and this awareness seemed to produce sharper, more definite lines of prose. It was as if, given the extra effort involved, he didn’t want to have to spend anymore time typing than he had to, so he would try to get it right the first time, or nearly so. Typewriters, he understood, had the same effect. Perhaps the pen as well. The costs they imposed concentrated the hand and the mind. His essays, or whatever they were, had benefitted. The roots seemed stronger.

Читать дальше