And so, drop by drop, Ryan fueled his airplane.

They were camped at the shore of what had, long ago, been an ocean. How many fossils were there in that ancient dry ocean bed, Estrela wondered? How far had life come? Had life on Mars emerged from its oceans, only to become extinct as the rivers dried and the planet froze? And what, exactly, had caused the oceans to evaporate and the atmosphere to leak away?

Estrela was beginning, slowly, to come out of the deep depression that had enveloped her over the last weeks. Eight days at the Agamemnon campsite had revived her. For the first three days she had stayed inside the habitat dome, and then she took to leaving the habitat dome for just one hour each day.

First she would walk over to the greenhouse module. She was amazed that it had survived, untended, for years on the Martian surface, and even had plants inside, some sort of tough yucca and several evergreen shrubs. She rubbed her hand over them, feeling the prickly points. You are like me, she told them silently. We are survivors.

Then she would go to walk along the deserted beach just before sunset.

The water of the ancient ocean was long gone; the sands of the beach had long ago cemented into a rocklike caliche. She could read the ebb and flow of the waves in the ripples frozen into the sandstone. She would find a shallow basin and brush away the covering dust, and find below the white layer of evaporite, salt crystals.

One time, walking a little inland, she found yet another fossil, embedded in the wall of a limestone cliff. It was exactly the same shape as the others, but this one was immense, as large as a whale, ten meters from end to end. Estrela wondered that these were the only type of fossils that they saw. Had there been only one form of life on Mars? Or perhaps only one type had fossilized.

And the sun would set, and she would return into the habitat.

Inside the dome was paradise, with plentiful liquids and warmth, with enough water to heat an entire liter of bathwater at once and let it dribble, sensuously, over her body. It felt like a decadent luxury.

Her throat no longer hurt so much. She could even speak, in a voice louder than a whisper.

She carefully plaited her now-blond hair, and barely wore clothing. Ryan was the one who would make the decision now, she knew. Two women, and he would be able to take only one home.

But Ryan barely looked at her, although she tried in a dozen subtle ways to contrive to be there, nearly naked, when he was in the habitat, and he would hardly have been able to miss her. But he never made a move.

Ryan was good-looking. Oh, not as good as João—Santa Luzia, who could possibly be as gorgeous as her beautiful João had been?—but he was fine. But he seemed to pay no attention to her.

Two women, and only one would get to go with him back home. Well, the odds were much better than they had been. She knew men, and knew that if there had been two men, somehow the men would have contrived a way to show that it was logical for the two men to go home to Earth and the women stay behind to die. It was just the way of the world.

She wondered if Tana knew how much she hated her.

At SPAR Aerospace, Ryan Martin worked on designing tether deployment systems for space; much later, his expertise on the use of tether systems played a major part in his role in the failed Mirusha rescue attempt. He spent a year in France, to earn a degree in space studies at the International Space University in Strasbourg, and the day he came back to Canada he put in his application to join the small Canadian astronaut corps.

His application went in just in time to apply to join the first Canadian cadre selected specifically for duty to the space station. His low amount of piloting time counted against him. He had taken flying lessons and spent as much time as he could afford practicing, but he certainly had far fewer hours in the air than the RCAF pilots that applied for the same few slots. But no one had a more thorough grasp of every aspect of astronautics and microgravity science than he, and in the end that counted more than his relative lack of flight hours. He wasn’t being trained to be a pilot anyway; the Americans would never select a Canadian to fly their shuttle. For the tasks Canada wanted astronauts for, they needed expertise in all areas, and no one scored higher than Ryan.

He graduated at the top of his astronaut training class.

His appointment to the astronaut corps elicited mixed feelings for him; during those years the fate of the space station was uncertain, and whether the space station had any role at all in the future exploration of space, or if instead it was an expensive orbiting dinosaur, was quite unclear. He wondered if the real future might instead lie in commercial space, where new, small launch vehicles were beginning to make enormous profits from launching tiny, cheap satellites.

But he wanted to do more than just send up other people’s satellites.

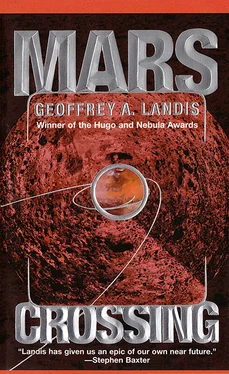

Ryan Martin wanted to go to Mars.

Mars was his obsession. He thought about Mars, made calculations, read every book, science or science fiction, that had ever been written about Mars, published papers suggesting possible solutions to the finicky engineering details of a Mars mission. After a while he started to be invited to give lectures about Mars missions, and he found that he was good at it. He would rent an airplane and fly to some distant city and talk. Schoolchildren, Masonic temples, library groups—he loved the moment when a group of strangers suddenly warmed up, and his contagious enthusiasm spread.

He didn’t chase women—to tell the truth, he had never learned how to approach a woman—it seemed to be an arcane trick that other men learned in some class he had failed to attend—and so he treated all the women he met exactly the same way he treated the men: as coworkers or as friends. But occasionally women would ask him out, and he wasn’t against going out to a restaurant, or to a concert, or for a walk on the beaches of Lake Ontario. And afterward, if sometimes a female friend asked him back to her apartment, or his, well, he had taken no vow of chastity.

He had only two rules to his relationships, rules that he never broke. Never promise anything.

And never fall in love.

Butterfly had been designed for short hops and aerial reconnaissance, not for a two-thousand-mile flight, and it had not been designed to carry three people. Over the months that they spent at Acidalia, Ryan ripped out every part that was not critical to flight: all the redundant control systems, the scientific instrumentation. He cut off the landing gear; when she landed, the Butterfly would land on snow. And she would never take off again.

They would have no margin, but at last he had an airplane that would make it to the pole.

For the take-off, Ryan laid down two strands of the superfiber cable for three kilometers along the desert sand. At the far end he staked it down to bolts drilled into bedrock, and then went back and used the motorized winch to stretch it. The elastic energy that can be stored in superfiber is enormous: If it were to suddenly break, the release would snap the cable back at almost hypersonic velocity, setting free enough energy to vaporize much of the cable, as well as anybody who stood nearby.

Once he had it stretched, he held it stretched with a second anchor bolt. It formed a two-mile-long rubber band. Ryan would use the world’s largest slingshot to launch the airplane.

The airplane had only two seats, so Estrela and Tana both were crammed into the rear copilot’s seat of the airplane, Estrela perched on Tana’s lap. In their bulky Mars suits, they fit into the space with barely millimeters to spare.

Читать дальше