“He’d been into Paris, this guy, and got rich on what he brought out,” Sam says. “He didn’t care about Ernst, Matta, Tanning, Fini, he just wanted things. He had one of you-know-who’s telephone, that was…” Her hands describe it. “A lobster. With wires. If you held it to your ear it would grab for you and get its legs tangled in your hair, but it could tell you secrets. It never said anything to me. It didn’t like me. But this guy told me it once whispered to him, ‘Fall Rot’s coming.’”

“That’s why you’re here,” says Thibaut. “To find out about this Fall Rot. Not to take photographs.” He feels betrayed.

“I am here for photographs. For The Last Days of New Paris. Remember?” She is playful in a way he doesn’t understand. “And to find a few other things out, too. A bit of information. That’s true. You don’t have to stay with me.”

Thibaut beckons the exquisite corpse through the dust of ruins. Sam flinches at its approach. “They’re chasing you,” Thibaut says. “You got a picture of something that got the Nazis worked up enough to track you. What is it has them so worried?”

“I don’t know,” she says. “I have a lot of pictures. I’d have to get out to develop them to figure it out and there’s more to photograph first. I can’t leave. I don’t know what’s going on yet. Don’t you want to know about Fall Rot?”

What Thibaut has wanted is out. To outrace those who follow, now maybe to find whatever image in Sam’s films holds some secret Nazi weakness, to use it against them. But to his own surprise something in him, even now, stays faithful to his Paris. He’s buoyed by the thought of Sam’s book, that swan song, that valedictory to a city not yet dead. He wants the book, and there are pictures to take. When he tries to think of leaving, Thibaut’s head gets foggy. It’s madness, but Not yet, he thinks, not before we’ve finished.

The book is important. He knows this.

He imagines an oversized volume, bound in leather, with hand-drawn endpapers. Or another, rougher edition, rushed out by some backstreet press. Thibaut wants to hold it. To see photographs of these walls on which the crackwork whispers and scratch-figures etched with keys shift; of the impossibilities he has fought, that now walk with him.

—

Are they hunting images, then, as well as information about Fall Rot? Whatever else, Thibaut decides, yes, they are.

He follows Sam north over a spill of architecture. Refit vehicles still line the streets, too-big sunflowers push their way through buildings, a quiet partisan leans cross-armed over a rifle in a top-floor window, watching them. She raises her hand to Thibaut in a wary salute that he returns.

Sam photographs. They sleep in shifts. At dawn a great shark mouth appears at the horizon smiling like a stupid angel and chewing silently on the sky.

Women and men committed to no side, to nothing except trying to live, have taken up paving stones and plowed up earth underneath. They farm amid changeable ruins, fighting Hellish things and feral dreams. They have made front-room schools for their children in townlets of a street or two, keep barricades up.

One such is close to where a house has gone. By their path, where the cellar was, the hole has filled with sodden grit. Thibaut slows here, can feel something. He stops Sam. He points. There are wet bones in the pit.

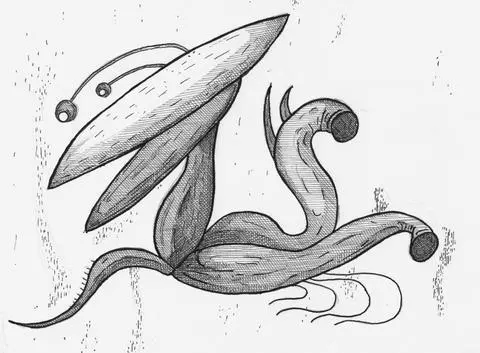

The travelers stay still and something twitches in the sludge. Snares of tubular parts tangle, untangle and rear. Water falls with a rushing sound away from a big vicious elliptical head rising, now the ambush has failed.

It is a sandbumptious, an ugly thing torn from an English painting. It eyes them with eyes on bobbing stems. Judging by the remains around it, it eats stragglers and scrawny horses, like most of its kind.

Sam takes a picture of the predator rising in the muck, and hissing. When she’s done, Thibaut braces his rifle on the remains of a wall. He focuses from his core.

His aim is not very good, but his focus can enhance his fire, his techniques are powerful, and the proximity of the exquisite corpse helps him. When he shoots his bullets slam into the hole and its inhabitant and the wallowing animal bleats and all in a rush, a single flame, at the wrong scale like the tip of a giant matchhead, takes it and goes out.

There is a burnt-out smell. The manif is dead.

As Thibaut and Sam walk on someone shouts “Hey!”

Wary faces rise into view above the nearby barrier. A tough-faced woman with her hair under a scarf throws Thibaut a bag of bread and vegetables. “We saw what you did,” she says.

“Thank you,” says a younger man in a flat hat, looking down his shotgun, “and no offense, but fuck off now, and stay away.” He watches the exquisite corpse.

“This?” Thibaut says. “It won’t cause you any trouble.”

“Fuck off and keep your Nazis away.”

“What? What did you call me?” Thibaut shouts. “I’m Main à plume!”

“You’ll bring them here!” the man shouts back. “Everyone knows you’re being hunted!” Sam and Thibaut look at each other.

“You heard of Wolfgang Gerhard?” Sam shouts. The young fighter shakes his head and gestures them away.

The wind explores the buildings. They hear firefights in distant streets. Thibaut and Sam descend a series of great declivities cracked in the pavement, that Thibaut realizes are the footprints of some giant.

—

Near the boulevard Montparnasse, Sam checks her charts and journals in the hard sunlight. An old woman watches Thibaut from a doorway. She beckons and when he comes to her, she hands him a glass of milk. He can hear a cow lowing in the cellar.

“Careful,” she says. “Devils are around.”

“For the catacombs?” he wonders. Their entrance is nearby, by the tollhouses called the Barrière d’Enfer.

She shrugs. “I don’t think even the Germans know what they’re doing. The observatory’s close,” she says, “and it’s full of astronomers from Hell. Round here when they look through the telescopes we see what they remember.”

The milk is cool and Thibaut drinks it slowly. “Can I do anything for you?” he says.

“Just be careful.”

In Place Denfert-Rochereau, the Lion of Belfort has disappeared from its plinth. Surrounding the empty platform where the black statue used to stare stiff-legged are now a crowd of stone men and women, all with the heads of lions.

Thibaut is happy among those frozen flaneurs. The exquisite corpse murmurs beside him.

Sam is agitated. She won’t or can’t come close, will only just enter the square. She takes pictures of the motionless crowd from the edge and watches him with a curious expression.

Élise, Thibaut thinks. Jean. You should be here. For the first time since the Bois de Boulogne he feels as if he is somewhere that he has fought for.

He should have played his card. I killed my friends, he thinks.

What treachery against the collectivism, the war socialism of the Main à plume, keeping the card for himself. He doesn’t even know what it would have done. But play is insurrection in the rubble of objective chance. That was the aspiration, the wager of the Surrealists trapped in the southern house.

“Historians of the playing card,” Breton said, “all agree that throughout the ages the changes it has undergone have always been at times of great military defeats.” Turn defeat into furious play. The story had reached Paris with its manifs. Breton, Char, Dominguez, Brauner, Ernst, Hérold, Lam, Masson, Lamba, Delanglade, and Péret, purveyors of the new deck. Genius, Siren, Magus usurping the pitiful aristocratic nostalgia of King, Queen, and Jack. Père Ubu the Joker, his spiraled stomach mesmeric.

Читать дальше