It treads behind them.

Thibaut has unwound his cosh and dangled the table-wrangler’s cord around one of the manif’s metal extrusions, what are not quite limbs. It is not a leash—it is not taut and Thibaut would never consider pulling—but he has one end of it and the manif does not object to wearing it, and joined by the bond the living art comes with Thibaut as though he holds its hand.

—

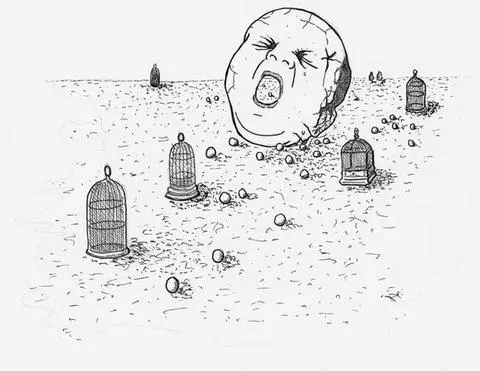

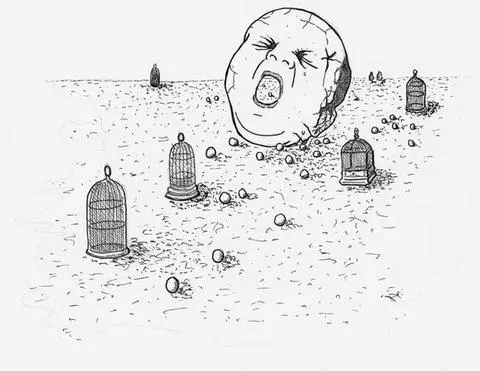

It is morning, a part of the city all razed into a flat ashy vista. They are in rubble full of birdcages. Some are empty, some contain silent watchful birds. A broken screen; a litter of toys’ heads cracked like shells; a motionless little girl-thing standing in her white dress and watching with a featureless hole where a child would have features. From her they keep their distance and their gazes. Far ahead of them a baby’s face the size of a room protrudes from the ground like some whaleback, staring skyward. It squawls quietly. Sam takes a picture.

Beyond boxes of preserved butterflies, they see drapery hanging from trees. They hear spectral guns. This place is a shooting range haunted by ghost bullets.

“This is Toyen’s landscape,” says Sam.

“I know what it is,” Thibaut says. “I’m Main à plume.”

The exquisite corpse picks through the dust. Sam looks at it with the same expression that she wore the previous night, when she at last slowed under a balcony poised during its deliquescence, and turned and stared at the manif.

She could not stop herself rearing back at the sight, and the exquisite corpse reared, too, and stamped. In alarm, Thibaut tried to hush it, had concentrated his attention to that end. To his amazement the thing calmed.

“They don’t like me,” Sam said.

“Manifs?” he said. “They don’t have any opinion about you.”

But when he at last persuaded her to take the rope, the exquisite corpse bared its teeth, and Sam let it go.

“It seems to know you’re an ally,” she said.

Now Thibaut flexes his intuition again. The manif exhales exhaust from its beard-train. It follows him like something that knows something.

In the sky a storm of birds takes the shape of one great bird, then of a dancing figure, before they scatter. Sam takes a picture of that, too.

“I was on my way out,” Thibaut says to her abruptly.

“When I found you.”

Sam waits.

“A while back, I met a woman riding a manif,” Thibaut starts again.

“The Vélo,” says Sam. “I heard something about that…”

“You heard?” Thibaut can feel the card in his pocket. “Well, I was there when her passenger died. And when I went through what she was carrying… I think she was a spy. Like your chocolate man.”

“Naturally.”

“British. SOE.” Thibaut holds up the cord he carries. “She was controlling her manif with leather, too. Or trying to. We didn’t keep the thong: we should’ve done. She had a map. With stars drawn on it, and notes.”

“What did the notes say?”

A constellated Paris. They had pulled the dirty thing from her inside pocket. “Most of them were crossed out,” Thibaut says. “They were the names of lost objects. They were famous manif things.” Thibaut looks at her and can see she understands. “I thought maybe she was a magpie. She was artifact hunting, for sure. But perhaps it wasn’t for her.”

“Had she found any?”

He feels as if the playing card is moving in his pocket. “Well,” he says. “She had none on her. Maybe she crossed them off when she found out they were gone.”

“Or took them and passed them on.”

He licks his lips. “So anyway,” he says. “Eventually, we used it. The map. Of course. My comrades and I. Went looking. Went to the Bois de Boulogne.”

“Why?”

“Because that was where there was a star that wasn’t crossed out.”

“I mean why eventually? Why didn’t you go hunting straightaway?”

“Oh.” He keeps his eyes on the horizon. “I persuaded them to wait.” His comrades had not known what for, but they had agreed. “I’d heard something about that other plan you mentioned. Never knew the details. Just that it was some assault. I thought we should wait, see if we heard anything. In case it succeeded.” She says nothing so he must continue.

“It didn’t,” he whispers. “It went wrong. Chabrun, Léo Malet and Tita, a lot of others. They died.”

“I heard,” Sam says. “Do you know what happened?”

“I think the enemy got wind of it. They hit first. And they must’ve had some… weapon. ” He bares his teeth. “I don’t know exactly what but our people—it was the best of us who died. The best. The Nazis must’ve had something ready to go into those streets.” He could, might have been there, with the now-dead. Then he would be dead, too.

Except if his presence would have changed things.

Thibaut had fought the Carlingue once, alongside Laurence Iché. A day full of flat light, the two of them patrolling, she showing the rookie the area. A routine sweep of a quiet zone. Expecting nothing, they walked into the remains of a battered lot, and an ambush.

He had hurled himself screaming for cover, trying to shoot as he went, trying to bring training to mind as he cowered under fire. When he turned and hauled himself half upright, Iché was stood there in her grubby floral dress, still smoking hard, ignoring all the bullets that crashed around her, raising her right arm.

She roared and a too-big eagle appeared and plunged straight for the men gathered at the cul-de-sac’s entrance. As Thibaut cowered and watched the wings beat down on them and they gasped and tried to run she had said something else and made a caterpillar longer and fatter than a horse with the head of a wicked bird, and it rippled after the eagle over the shattered brick. Thibaut heard cries and wet noises. Iché brought a bathtub full of glimmering, shredded mirror into presence and sent it skittering on its claw feet into the slack-faced Gestapo commander. It bumped him and caught him with all its grinding scintillas. He screamed and sent up a spray of blood and reflections.

“I saw Iché manifest her own poems once,” he says. “Not many could do that.”

“Maybe your comrades had some secret weapon, too,” Sam says. “I heard things.”

“So you keep saying. I don’t know. I don’t know if they had what they wanted. If there was anything.”

“Well, there were stories. About a fight. Between something manif of theirs—yours— and something Nazi—”

“I heard rumors, too,” Thibaut interrupts, making her blink. “If they had a secret weapon it didn’t fucking work, did it?”

“Is that why you’re leaving?” Sam says after a moment. He does not reply. “What was it happened in the forest?” she says. “Did you find what you were looking for?”

“I should’ve fucking left then,” he says. “As soon as I heard about that fiasco. That they were gone. But I stayed. We all stayed. Decided to follow the map.”

His cell. Around a fire. Drinking to the memory of the dead. The identities of whom they were not even quite sure. They knew, though, from the tenor of the rumors they had already heard, the transmissions in garbled code passed on by runners at arrondissement edges, reaching them at last, from the shift in the atmosphere, for those like Thibaut who could feel it, that this failed assault changed things. That a chance had been lost, for their side.

None of them slept that night, after the word reached them, word they could not be sure was true but were quite sure was true. They gathered together and talked quietly, tried to reconstruct which of the great booms across the city that they’d heard over the last week had been the noise of their comrades falling, according to what bad powers.

Читать дальше