“Mr. Harrington,” asked the waitress, “don’t you like your pie?”

“Certainly,” said Harrington, picking up the fork and cutting off a bite.

So pretending was the pay, the ability to pretend without conscious effort a private world in which he moved alone. And perhaps it was even more than that—perhaps it was a prior condition to his writing as he did, the exact kind of world and life in which it had been calculated, by whatever means, he would do his best.

And the purpose of it?

He had no idea what the purpose was.

Unless, of course, the body of his work was a purpose in itself.

The music in the radio cut off and a solemn voice said: “We interrupt our program to bring you a bulletin. The Associated Press has just reported that the White House has named Senator Johnson Enright as secretary of state. And now, we continue with our music….”

Harrington paused with a bite of pie poised on the fork, halfway to his mouth.

“The hallmark of destiny,” he quoted, “may rest upon one man!”

“What was that you said, Mr. Harrington?”

“Nothing. Nothing, miss. Just something I remembered. It’s really not important.”

Although, of course, it was.

How many other people in the world, he wondered, might have read a certain line out of one of his books? How many other lives might have been influenced in some manner from the reading of a phrase that he had written?

And had he had help in the writing of those lines? Did he have actual talent or had he merely written the thoughts that lay in other minds? Had he had help in writing as well as in pretending? Might that be the reason now he felt so written out?

But however that might be, it was all over now. He had done the job and he had been fired. And the firing of him had been as efficient and as thorough as one might well expect—all the mumbo-jumbo had been run in competent reverse, beginning with the man from the magazine this morning. Now here he sat, a humdrum human being perched upon a stool, eating cherry pie.

How many other humdrum humans might have sat, as he sat now, in how many ages past, released from their dream-life as he had been released, trying with no better luck than he was having to figure out what had hit them? How many others, even now, might still be living out a life of make-believe as he had lived for thirty years until this very day?

For it was ridiculous, he realized, to suppose he was the only one. There would be no point in simply running a one-man make-believe.

How many eccentric geniuses had been, perhaps, neither geniuses nor eccentric until they, too, had sat in some darkened corner with a faceless being and listened to his offer?

Suppose—just suppose—that the only purpose in his thirty years had been that Senator Johnson Enright should not retire from public life and thus remain available to head the state department now? Why, and to whom, could it be so important that one particular man got one certain post? And was it important enough to justify the use of one man’s life to achieve another’s end?

Somewhere, Harrington told himself, there had to be a clue. Somewhere back along the tangled skein of those thirty years there must be certain signposts which would point the way to the man or thing or organization, whatever it might be.

He felt dull anger stirring in him, a formless, senseless, almost hopeless anger that had no direction and no focal point.

A man came in the door and took a stool one removed from Harrington.

“Hi, Gladys,” he bellowed.

Then he noticed Harrington and smote him on the back. “Hi, there, pal,” he trumpeted. “Your name’s in the paper.”

“Quiet down, Joe,” said Gladys. “What is it that you want?”

“Gimme a hunk of apple pie and a cuppa coffee.”

The man, Harrington saw, was big and hairy. He wore a Teamsters badge.

“You said something about my name being in the paper.”

Joe slapped down a folded paper.

“Right there on the front page. The story there with your picture in it.”

He pointed a grease-stained finger.

“Hot off the press,” he yelped and burst into gales of laughter.

“Thanks,” said Harrington.

“Well, go ahead and read it,” Joe urged boisterously. “Or ain’t you interested.”

“Definitely,” said Harrington.

The headline said:

NOTED AUTHOR WILL RETIRE

“So you’re quitting,” blared the driver. “Can’t say I blame you, pal. How many books you written?”

“Fourteen,” said Harrington.

“Gladys, can you imagine that! Fourteen books! I ain’t even read that many books in my entire life…”

“Shut up, Joe,” said Gladys, banging down the pie and coffee.

The story said:

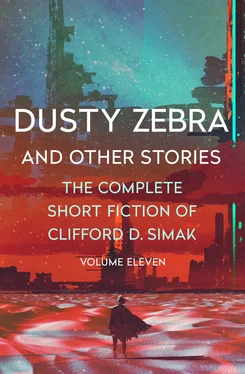

Hollis Harrington, author of See My Empty House, which won him the Nobel prize, will retire from the writing field with the publication of his latest work, Come Back, My Soul.

The announcement will be made in this week’s issue of Situation magazine, under the byline of Cedric Madison, book editor.

Harrington feels, Madison writes, that he has finally, in his forthcoming book, rounded out the thesis which he commenced some thirty years and thirteen books ago…

Harrington’s hand closed convulsively upon the paper, crumpling it.

“Wassa matter, pal?”

“Not a thing,” said Harrington.

“This Madison is a jerk,” said Joe. “You can’t believe a thing he says. He is full of…”

“He’s right,” said Harrington. “I’m afraid he’s right.”

But how could he have known? He asked himself. How could Cedric Madison, that queer, devoted man who practically lived in his tangled office, writing there his endless stream of competent literary criticism, have known a thing like this? Especially, Harrington told himself, since he, himself, had not been sure of it until this very morning.

“Don’t you like your pie?” asked Joe. “And your coffee’s getting cold.”

“Leave him alone,” said Gladys, fiercely. “I’ll warm up his coffee.”

Harrington said to Joe: “Would you mind if I took this paper?”

“Sure not, pal. I’m through with it. Sports is all I read.”

“Thanks,” said Harrington. “I have a man to see.”

The lobby of the Situation building was empty and sparkling—the bright, efficient sparkle that was the trademark of the magazine and the men who made it.

The 12-foot globe, encased in its circular glass shield, spun slowly and majestically, with the time-zone clocks ranged around its base and with the keyed-in world situation markers flashing on its surface.

Harrington stopped just inside the door and glanced around, bewildered and disturbed by the brightness and the glitter. Slowly he oriented himself. Over there the elevators and beside them the floor directory board. There the information counter, now unoccupied, and just beyond it the door that was marked:

HARVEY

Visiting Hours

9 to 5 on Week Days

Harrington crossed to the directory and stood there, craning his neck, searching for the name. And found it.

CEDRIC MADISON… 317

He turned from the board and pressed the button for the elevator.

On the third floor the elevator stopped and he got out of it and to his right was the newsroom and to his left a line of offices flanking a long hall.

He turned to the left and 317 was the third one down. The door was open and he stepped inside. A man sat behind a desk stacked high with books, while other books were piled helter-skelter on the floor, and still others bulged the shelves upon the walls.

“Mr. Madison?” asked Harrington and the man looked up from the book that he was reading.

And suddenly Harrington was back again in that smoky, shadowed booth where long ago he’d bargained with the faceless being—but no longer faceless. He knew by the aura of the man and the sense of him, the impelling force of personality, the disquieting, obscene feeling that was a kind of psychic spoor.

Читать дальше