Monk found a cigarette and lighted it, listening to the pelting of the sand against the window. But there was a strange sound, too. Something that was not sand tapping on the panes, nor yet the shrill keening of the savage wind that moaned against the building. A faint whining that bore a pattern of melody, the sobbing of music—music that sneaked in and out of the wind blasts until one wondered if it was really there or was just imagination.

Monk sat stiffly, poised, cigarette drooping, ears straining.

It came again, the cry of strings, the breath of lilting cadence, until it was a thing apart from the wind and the patter of the sand.

A violin! Someone playing a violin inside the museum!

Monk leaped to his feet and suddenly the violin screamed in singing agony.

And even as that melodic scream ran full-voiced through the hall outside, a sharp bell of warning clanged inside Monk’s brain.

Acting on impulse, his hand shot down and snatched up the Asteroid jewel. Clutching it savagely, he hurled it viciously against the metallic side of the manuscript cabinet.

It flashed for a moment in the light as it exploded into tiny bits of glowing dust. And even as it splashed to shards, it changed—or tried to change. For just a moment it was not a jewel, but something else, a fairylike thing—but a crippled fairy. A fairy with humped back and crooked spine and other curious deformities.

Then there was no twisted fairy, but only jewel dust twinkling on the floor and the sound of running feet far down the corridor.

Monk did not try to give chase to the man outside. Instead, he stood as if frozen, listening to the wind and the sand dance on the window, staring at the sparkle on the floor.

He slowly closed and opened his right hand, trying to remember just how the jewel had felt at the instant he had clutched it. Almost as if it might have been alive, were struggling to get out of his clutches, fighting to attain some end, to carry out some destiny.

His eyes still were upon the floor.

“Now,” he said aloud, amazement in his words, “I wonder why I did that?”

Standing in front of Spencer Chambers’ desk, Harrison Kemp was assailed by doubt, found that in this moment he could not reconcile himself to the belief he had done the right thing. If he were wrong, he had deserted a post he should have kept. Even if he were right, what good could his action do?

“I remember you very well,” he heard Chambers say. “You have been out on Pluto. Life research. Some real achievements in that direction.”

“We have failed too often,” Kemp told him flatly.

Chambers matched his fingers on the desk in front of him. “We all fail too often,” Chambers said. “And yet, some day, some one of us will succeed, and then it will be as if all of us succeeded. We can write off the wasted years.”

Kemp stood stiff and straight. “Perhaps you wonder why I’m here.”

Chambers smiled a little. “Perhaps I do. And yet, why should I. You have been gone from Earth for a long time. Perhaps you wanted to see the planet once again.”

“It wasn’t that,” Kemp told him. “It’s something else. I came because I am about to go insane.”

Chambers gasped involuntarily.

“Say that again,” he whispered. “Say it slowly. Very slowly.”

“You heard me,” said Kemp. “I came because I’m going to crack. I came here first. Then I’m going out to Sanctuary. But I thought you’d like to know—well, know, that a man can tell it in advance.”

“Yes,” said Chambers, “I want to know. But even more than that. I want to know how you can tell.”

“I couldn’t myself,” Kempt told him. “It was Findlay who knew.”

“Findlay?”

“A man who worked with me on Pluto. And he didn’t really know. What I mean is he had no actual evidence. But he had a hunch.”

“A hunch?” asked Spencer Chambers. “Just a hunch? That’s all?”

“He’s had them before,” Kemp declared. “And they’re usually right. He had one about Johnny Gardner before Johnny cracked up. Told me I should send him back. I didn’t. Johnny cracked.”

“Only about Johnny Gardner?”

“No, about other things as well. About ways to go about our research, ways that aren’t orthodox. But they usually bring results. And about what will happen the next day or the day after that. Just little inconsequential things. Has a feeling, he says—a feeling for the future.”

Chambers stirred uneasily. “You’ve been thinking about this?” he asked. “Trying to puzzle it out. Trying to explain it.”

“Perhaps I have,” admitted Kemp, “but not in the way you mean. I’m not crazy yet. May not be tomorrow or next week or even next month. But I’ve watched myself and I’m pretty sure Findlay was right. Small things that point the way. Things most men would just pass by, never give a second thought. Laugh and say they were growing old or getting clumsy.”

“Like what?” asked Chambers.

“Like forgetting things I should know. Elemental facts, even. Having to think before I can tell you what seven times eight equals. Facts that should be second nature. Trying to recall certain laws and fumbling around with them. Having to concentrate too hard upon laboratory technique. Getting it all eventually, even quickly, but with a split-second lag.”

Chambers nodded. “I see what you mean. Maybe the psychologists could help—”

“It wouldn’t work,” declared Kemp. “The lag isn’t so great but a man could cover up. And if he knew someone was watching he would cover up. That would be instinctive. When it becomes noticeable to someone other than yourself it’s gone too far. It’s the brain running down, tiring out, beginning to get fuzzy. The first danger signals.”

“That’s right,” said Chambers. “There is another answer, too. The psychologists, themselves, would go insane.”

He lifted his head, appeared to stare at Kemp.

“Why don’t you sit down?” he asked.

“Thank you,” said Kemp. He sank into a chair. On the desk the spidery little statue moved with a scuttling shamble and Kemp jumped in momentary fright.

Chambers laughed quietly. “That’s only Hannibal.”

Kemp stared at Hannibal and Hannibal stared back, reached out a tentative claw.

“He likes you,” said Chambers in surprise. “You should consider that a compliment, Kemp. Usually he simply ignores people.”

Kemp stared stonily at Hannibal, fascinated by him. “How do you know he likes me?”

“I have ways of knowing,” Chambers said.

Kemp extended a cautious finger, and for a moment Hannibal’s claw closed about it tightly, but gently. Then the grotesque little being drew away, squatted down, became a statue once again.

“What is he?” Kemp asked.

Chambers shook his head. “No one knows. No one can even guess. A strange form of life. You are interested in life, aren’t you, Kemp?”

“Naturally,” said Kemp. “I’ve lived with it for years, wondering what it is, trying to find out.”

Chambers reached out and picked up Hannibal, put him on his shoulder. Then he lifted a sheaf of papers from his desk, shuffled through them, picked out half a dozen sheets.

“I have something here that should interest you,” he said. “You’ve heard of Dr. Monk.”

Kemp nodded. “The man who found the Rosetta scroll of Mars.”

“Ever meet him?”

Kemp shook his head.

“Interesting chap,” said Chambers. “Buried neck-deep in his beloved Martian manuscripts. Practically slavering in anticipation, but getting just a bit afraid.”

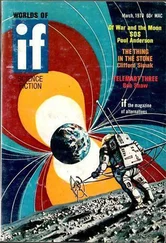

He rustled the sheets. “I heard from him last week. Tells me he has found evidence that life, a rather queer form of life, once existed on the fifth planet before it disrupted to form the Asteroids. The Martians wrote that this life was able to encyst itself, live over long periods in suspended animation. Not the mechanically induced suspended animation the human race has tried from time to time, but a natural encystation, a variation of protective coloration.”

Читать дальше