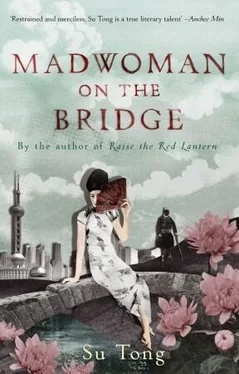

Su Tong

Madwoman On the Bridge and Other Stories

The mad woman on the bridge wears a historical gown which she refuses to take off. In the height of summer, to the derision of the townspeople, she stands madly on the bridge. Until a young female doctor, bewitched by the beauty of the mad woman’s dress, plots to take it from her, with tragic consequences.

Set during the fall-out of the Cultural Revolution, these bizarre and delicate stories capture magnificently the collision of the old China of vanished dynasties, with communism and today’s tiger economy.

From the folklorist who becomes the victim of his own rural research, to the doctor whose infertility treatment brings about the birth of a monster child, to a young thief who steals a red train only to have it stolen from him, Su Tong’s stories are a scorching look at humanity.

The madwoman was wearing a white velvet cheongsam, and in her hand she held a sandalwood fan. Standing on the bridge, she revelled in her own elegance. For those who knew her this was not at all surprising, but other passersby assumed she was an actress here to shoot some footage. She gazed around her and raised her fan to wave at the children going past, but they ignored her. The boys stuck out their tongues and grimaced, hoping to frighten her, while the girls pointed at her cheongsam and, whispering confidentially, paid no further attention to her.

They were like lively clouds, floating one by one across the bridge, only to disperse at the slightest puff of wind. The madwoman’s constant companion was a pot of chrysanthemums, which stood watch over the bridge with her. November chrysanthemums: from a distance, they seemed still to be in bloom, but up close you could see how they dropped. Just like the madwoman. At first glance she seemed beautiful, but closer scrutiny revealed that she was as faded as her flowers.

The madwoman on the bridge appeared very lonely, unbearably so in fact, for she kept twisting her head and body this way and that, looking from side to side. Her brow furrowed as she glanced over at Mahogany Street, on the near side of the bridge, then mumbled something which sounded like a complaint. What was she complaining about? Or whom? No one cared.

Besides the pot of chrysanthemums, her intimacy extended only to the sandalwood fan. All those who knew her were familiar with this article: it was dark yellow, threaded with gold and had green tassels hanging from the handle. You could smell its fragrance from far away. Although the season for using sandalwood fans was already long past, the madwoman clutched hers whenever she went out. She spread the fan so it shaded her brow; golden strips of sunlight slatted her pale countenance. At times it looked like dazzling make-up, at others like terrible scars.

Occasionally, when the figure of an acquaintance floated towards her over the bridge, the madwoman’s dim eyes would glint suddenly, and her whole body would set itself in motion to strike a seductive pose. She would wave at them with her fan, slowly undulating her svelte waist in greeting. Then she would poke playfully at their hands with her fan and say, ‘Oh, the heat. I’m just burning up.’ At this point, whoever she addressed would avert their face and glance towards the bridge. They wore impatient expressions, for they were normal people, and normal people pay no attention to madwomen. They just waved her away unfeelingly and hurried from the bridge. To be honest, there weren’t very many people on our street who embodied the warm-hearted spirit of revolutionary humanitarianism. I don’t know whether the old woman from Shaoxing was one of these or not, and it doesn’t much matter now either way, but I do know that the Shaoxing woman stayed on the bridge that afternoon to talk to the madwoman; she stayed for quite a long time.

The old Shaoxing woman had bound feet, but still undertook to deliver milk to the whole of Mahogany Street. Since feet were bound for aesthetic delight rather than practicality, the Shaoxing woman had trouble walking, and had to pause every few metres as she pushed her little cart. She shouted rhythmically as she walked to keep her spirits up. Her afternoon was devoted to collecting the empty bottles, and as she hobbled along, she groaned for people to bring them out. Today the Shaoxing woman had about thirty bottles as she tottered onto the bridge.

As usual, the madwoman remarked, ‘Oh, the heat. I’m just burning up.’

The Shaoxing woman took a handkerchief from her bosom to wipe away the sweat and replied nonchalantly, ‘Yes, I’m sweating like a pig.’ Suddenly she realized who she was speaking to and cried out in surprise, ‘Oh, what are you doing here? Why aren’t you at home like you should be? What did you come here for?’

The madwoman opened her fan and wafted it a few times, saying, ‘It was so hot, I came to the bridge for the breeze.’

The Shaoxing woman gave her a hard look and, sizing up the situation in an instant, said, ‘I don’t think so. It looks more like you were worried your cheongsam might go mouldy in its chest, so you thought you’d come here to show yourself off. Do you know what season this is? You must think it’s still summer, coming out here wearing your cheongsam and waving that fan around. Winter’s coming on, you know!’

The madwoman seemed unconvinced; she looked up at the sky, then reached out one hand to pass it over the chrysanthemums. ‘Summer’s over? But the chrysanthemums are still blooming. How could summer be over?’ she mumbled to herself. Then, suddenly, her eyes lit up as she asked, ‘When will winter start? When it does, I should wear my fox-fur coat.’

The Shaoxing woman gave a startled sound and replied, ‘How can you still bother yourself with things like that? Haven’t you been through enough already? Look at you, all dressed up and looking like a fright. That’s what made them terrorize you in the first place — and that’s what made you ill. Don’t you understand?’

The madwoman did not, and remarked, ‘With the fox-fur coat I’d have to wear matching boots. What a shame they stole my lambskin boots.’

The thought of her lost finery caused a mournful expression to appear on her face. She walked a melancholy circle around the Shaoxing woman’s cart, then another. ‘No more high-heeled shoes,’ she said with a glance at her feet. ‘No more jade bracelets,’ she said with a glance at her wrists. ‘No silk stockings either,’ she said, stroking her knees.

The Shaoxing woman couldn’t suppress a cry of protest, ‘They’re gone, and rightly so! Otherwise you’d probably be dead by now! Don’t you understand?’

The madwoman did not and lowered her head to study the milk bottles in the cart, or more specifically the multicoloured silk threads wound around the empty mouths of the bottles. ‘Look how pretty those threads are,’ she said. ‘Won’t you give them to me so I can weave Susu an egg cosy? At mid-autumn festival next year we can hang salted eggs in it.’

But the Shaoxing woman protested. ‘You’re not going to make a fool of me again. Last year I washed all those threads and gave them to you, and what happened? Before you even got home, you’d given them all away. Susu didn’t get a single one, poor thing. What a shame such a sensible girl is saddled with a mother like you!’

The Shaoxing woman was old and her vision fading. She hadn’t noticed at first that the madwoman was wearing a brooch. But when she bent down to put the milk bottles in order and looked up again at the madwoman, she caught sight of something on her chest: something sparkling, glistening in the sun. It was quite dazzling, and the Shaoxing woman gazed at it vacantly for a moment in disbelief. ‘Oh, no! Whatever possessed you to go out with that on? A treasure like that. it cost your grandmother a bar of gold. Quick, take it off!’

Читать дальше