Faith had failed because it had been blinded by the shining glory of itself. Could fact as well have failed by the hard glitter of its being?

But abandoning both faith and fact, armed with a greater tool of discernment, might a man not seek and find the eventual glory and the goal for which life had grasped, knowing and unknowing, from the first faint stir of consciousness upon the myriad solar systems?

Lathrop found the tube of white and unscrewed the cap and squeezed the tube and a bit of oil came out, a tiny drop of oil. He held the tube steady in one hand and picked up a brush. Carefully he transferred the color to the brush.

He dropped the tube and walked across the burrow to the painting and squatted down and squinted at it in the feeble light, trying to make out the source of the flood of light.

Up in the left hand corner, just above the horizon, although he couldn’t be entirely sure that he was right.

He extended the brush, then drew it back.

Yes, that must be it. A man would stand beneath the massive trees and face toward the light.

Careful now, he thought. Very, very careful. Just a faint suggestion, for it was mere symbolism. Just a hint of color. One stroke perpendicular and a shorter one at right angle, closer to the top.

The brush was awkward in his hand.

It touched the canvas and he pulled it back again.

It was a silly thing, he thought. A silly thing and crazy. And, besides, he couldn’t do it. He didn’t know how to do it. Even at his lightest touch, it would be crude and wrong. It would be desecration.

He let the brush drop from his fingers and watched it roll along the floor.

I tried, he said to Clay.

Although this story features, at least in passing, a number of elements Clifford Simak would return to, time and again, in his stories—drugs from space, the too rapid development of technology, telepathy—the basis of “Hunch” is its exposition of what Cliff described, in various later works (such as the novel Ring Around the Sun ), as a new sort of human sense, or perhaps power—the sense of hunch—a kind of new instinct arising in humankind to provide protection from a new kind of danger, arising when ordinary intelligence was not enough.

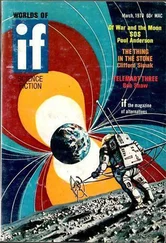

John W. Campbell Jr., the legendary editor of Astounding Science Fiction , took less than two weeks to accept this story after Cliff Simak sent it to him; Campbell paid him $150 and published it in the July 1943 issue of his magazine.

Sadly, this story does not work well; and I have believed for some time that it represents the skeleton of what should have been a longer, better developed, work. I regret that that story never made it into reality.

—dww

Hannibal was daydreaming again and Spencer Chambers wished he’d stop. Chambers, as chairman of the Solar Control Board, had plenty of things to worry about without having his mind cluttered up with the mental pictures Hannibal kept running through his brain. But, Chambers knew, there was nothing he could do about it. Daydreaming was one of Hannibal’s habits, and since Chambers needed the spidery little entity, he must put up with it as best he could.

If those mental pictures hadn’t been so clear, it wouldn’t have been so bad, but since Hannibal was the kind of thing he was they couldn’t be anything but clear.

Chambers recognized the place Hannibal was remembering. It wasn’t the first time Hannibal had remembered it and this time, as always, it held a haunting tinge of nostalgia. A vast green valley, dotted with red boulders splotched with gray lichens, and on either side of the valley towering mountain peaks that reached spear-point fingers toward a bright-blue sky.

Chambers, seeing the valley exactly as Hannibal saw it, had the uncomfortable feeling that he knew it, too—that in the next instant he could say its name, could give its exact location. He had felt that way before, when the identification of the place, just as now, seemed at his fingertips. Perhaps it was just an emotional hallucination brought about by Hannibal’s frequent thinking of the place, by the roseate longing with which he invested it. Of that, however, Chambers could not be sure. At times he would have sworn the feeling was from his own brain, a feeling of his own, set apart and distinct from Hannibal’s daydreams.

At one time that green valley might have been Hannibal’s home, although it seemed unlikely. Hannibal had been found in the Asteroid Belt, to this day remained the only one of his species to be discovered. And that valley never could have been in the Asteroids, for the Belt had no green valleys, no blue skies.

Chambers would have liked to question Hannibal, but there was no way to question him—no way to put abstract thoughts into words or into symbols Hannibal might understand. Visual communication, the picturing of actualities, yes—but not an abstract thought. Probably the very idea of direct communication of ideas, in the human sense, was foreign to Hannibal. After months of association with the outlandish little fellow, Chambers was beginning to believe so.

The room was dark except for the pool of light cast upon the desk top by the single lamp. Through the tall windows shone the stars and a silvery sheen that was the rising moon gilding the tops of the pines on the nearby ridge.

But darkness and night meant nothing to either Chambers or Hannibal. For Hannibal could see in the dark, Chambers could not see at all. Spencer Chambers was blind.

And yet, he saw, through the eyes—or, rather, the senses of Hannibal. Saw far plainer and more clearly than if he had seen with his own eyes. For Hannibal saw differently than a man sees—much differently, and better.

That is, except when he was daydreaming.

The daydream faded suddenly and Chambers, brain attuned to Hannibal’s sensory vibrations, looked through and beyond the walls of his office into the reception room. A man had entered, was hanging up his coat, chatting with Chambers’ secretary.

Chambers’ lips compressed into straight, tight lines as he watched. Wrinkles creased his forehead and his analytical brain coldly classified and indexed once again the situation which he faced.

Moses Allen, he knew, was a good man, but in this particular problem he had made little progress—perhaps would make little progress, for it was something to which there seemed, at the moment, no answer.

As Chambers watched Allen stride across the reception room his lips relaxed a bit and he grinned to himself, wondering what Allen would think if he knew he was being spied upon. Moses Allen, head of the Solar Secret Service, being spied upon!

No one, not even Allen, knew the full extent of Hannibal’s powers of sight. There was no reason, Chambers realized, to have kept it secret. It was just one of his eccentricities, he admitted. A little thing from which he gained a small, smug satisfaction—a bit of knowledge that he, a blind man, hugged close to himself.

Inside the office, Allen sat down in a chair in front of Chambers’ desk, lit a cigarette.

“What is it this time, chief?” he asked.

Chambers seemed to stare at Allen, his dark glasses like bowls of blackness against his thin, pale face. His voice was crisp, his words clipped short.

“The situation is getting worse, Moses. I’m discontinuing the station on Jupiter.”

Allen whistled. “You’d counted a lot on that station.”

“I had,” Chambers acknowledged. “Under the alien conditions such as exist on that planet I had hoped we might develop a new chemistry, discover a new pharmacopoeia. A drug, perhaps, that would turn the trick. Some new chemical fact or combination. It was just a shot in the dark.”

“We’ve taken a lot of them,” said Allen. “We’re just about down to a point where we have to play our hunches. We haven’t much else left to play.”

Читать дальше