He stopped short.

“Bill,” he spoke scarcely above a whisper, “am I seeing things?”

Before him, set on the sands of the arena, only a few yards from the plane, was a statute of heroic size, a statue of himself and Bill.

Even from where he stood he could read the inscription, carved in the white stone base of the statue in characters which closely resembled written English.

Slowly, haltingly, he read it aloud, stumbling over an occasional queer character.

“Two men, Harl Swanson and Bill Kressman, came out of time to kill Golan-Kirt and to free the race.”

Below it he saw other characters.

“They may return.”

“Bill,” he sobbed, “we haven’t traveled back in time. We have traveled further into the future. Look at that stone—eroded, ready to crumble to pieces. That statue has stood there for thousands of years!”

Bill slumped back into his seat, his face ashen, his eyes staring.

“The old man was right,” he screamed. “He was right. We’ll never see the twentieth century again.”

He leaned over toward the time machine.

His face twitched.

“Those instruments,” he shrieked, “those damned instruments! They were wrong. They lied, they lied!”

With his bare fists he beat at them, smashing them, unaware that the glass cut deep gashes and his hands were smeared with blood.

Silence weighed down over the plain. There was absolutely no sound.

Bill broke the silence.

“The future-men,” he cried, “where are the future-men?”

He answered his own question.

“They are all dead,” he screamed, “all dead. They are starved—starved because they couldn’t manufacture synthetic food. We are alone! Alone at the end of the world!”

Harl stood in the door of the plane.

Over the rim of the amphitheater the huge red sun hung in a sky devoid of clouds. A slight wind stirred the sand at the base of the crumbling statue.

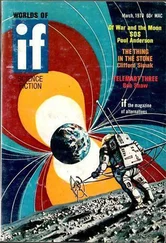

Although Clifford D. Simak sent this story to his agent under the title “Skirmish,” it would first appear in the December 1950 issue of Amazing Stories under the melodramatic title “Bathe Your Bearings in Blood.” And while this editor confesses that he rather likes the latter title, it appears here under its original title, since it is clear that Cliff deliberately restored the initial title for all further appearances of the story. Cliff was paid $114.75 for that first publication (a strange number that may result from the commission taken by his agent, Fred Pohl).

The story is old enough that it contains a couple of anachronisms that should perhaps be explained: To “tie the can” on someone was a euphemism for firing that person from his or her job and the Daily Worker was a publication of the government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics that was generally thought of, in Western literary and journalistic circles, as an unusually ham-fisted propaganda rag of no redeeming social value.

It is probably useless to engage in speculations about whether this story was an ancestor of Fred Saberhagen’s “Berserker” stories, or even of the (much later) “Transformer” movies. But I would suggest that Cliff Simak, having already written a number of stories featuring benign robots, including some of the stories in the City cycle, might have been examining the obverse of the robot coin with a certain relish …

—dww

It was a good watch. It had been a good watch for more than thirty years. His father had owned it first and his mother had saved it for him after his father died and had given it to him on his eighteenth birthday. For all the years since then it had served him faithfully.

But now, comparing it with the clock on the newsroom wall, looking from his wrist to the big face of the clock over the coat cabinets, Joe Crane was forced to admit that his watch was wrong. It was an hour fast. His watch said seven o’clock and the clock on the wall insisted it was only six.

Come to think of it, it had seemed unusually dark driving down to work, and the streets had appeared singularly deserted.

He stood quietly in the empty newsroom, listening to the muttering of the row of teletype machines. Overhead lights shone here and there, gleaming on waiting telephones, on typewriters, on the china whiteness of the pastepots huddled in a group on the copy desk.

Quiet now, he thought, quiet and peace and shadows, but in another hour the place would spring to life. Ed Lane, the news editor, would arrive at six-thirty and shortly after that Frank McKay, the city editor, would come lumbering in.

Crane put up a hand and rubbed his eyes. He could have used that extra hour of sleep. He could have…

Wait a minute! He had not gotten up by the watch upon his wrist. The alarm clock had awakened him. And that meant the alarm clock was an hour fast, too.

“It don’t make sense,” said Crane, aloud.

He shuffled past the copy desk, heading for his chair and typewriter. Something moved on the desk alongside the typewriter—a thing that glinted, rat-sized and shiny and with a certain, undefinable manner about it that made him stop short in his tracks with a sense of gulping emptiness in his throat and belly.

The thing squatted beside the typewriter and stared across the room at him. There was no sign of eyes, no hint of face, and yet he knew it stared.

Acting almost instinctively, Crane reached out and grabbed a pastepot off the copy desk. He hurled it with a vicious motion and it became a white blur in the lamplight, spinning end over end. It caught the staring thing squarely, lifted it and swept it off the desk. The pastepot hit the floor and broke, scattering broken shards and oozy gobs of half-dried paste.

The shining thing hit the floor somersaulting. Its feet made metallic sounds as it righted itself and dashed across the floor.

Crane’s hand scooped up a spike, heavily weighted with metal. He threw it with a sudden gush of hatred and revulsion. The spike hit the floor with a thud ahead of the running thing and drove its point deep into the wood.

The metal rat made splinters fly as it changed its course. Desperately, it flung itself through the three-inch opening of a supply cabinet door.

Crane sprinted swiftly, hit the door with both his hands and slammed it shut.

“Got you,” he said.

He thought about it, standing with his back against the door.

Scared, he thought. Scared silly by a shining thing that looked something like a rat. Maybe it was a rat, a white rat. And, yet, it hadn’t had a tail. It didn’t have a face. Yet it had looked at him.

Crazy, he said. Crane, you’re going nuts.

It didn’t quite make sense. It didn’t fit into this morning of October 18, 1952. Nor into the twentieth century. Nor into normal human life.

He turned around, grasped the door knob firmly and wrenched, intending to throw it wide open in one sudden jerk. But the knob slid beneath his fingers and would not move and the door stayed shut.

Locked, thought Crane. The lock snapped home when I slammed the door. And I haven’t got the key. Dorothy has the key, but she always leaves it open because it’s hard to get it open once it’s locked. She almost always has to call one of the janitors. Maybe there’s some of the maintenance men around. Maybe I should hunt one up and tell him—

Tell him what? Tell him I saw a metal rat run into the cabinet? Tell him I threw a pastepot at it and knocked it off the desk? That I threw a spike at it, too, and to prove it, there’s the spike sticking in the floor.

Crane shook his head.

He walked over to the spike and yanked it from the floor. He put the spike back on the copy desk and kicked the fragments of the pastepot out of sight.

Читать дальше