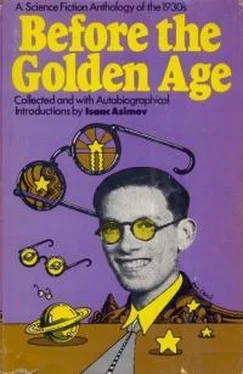

Айзек Азимов - Before The Golden Age

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Айзек Азимов - Before The Golden Age» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Before The Golden Age

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Before The Golden Age: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Before The Golden Age»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Before The Golden Age — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Before The Golden Age», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sam bristled at that. No man likes to hear his own century impugned, and another cried up in its place, especially by the member of a third epoch. “Perhaps,” he said heatedly, “I have been a bit more honest in my descriptions than Kleon. For example, he told you nothing of the slavery that existed in his day, the very fundamental upon which his civilization was based.”

“I see nothing wrong in that,” Kleon declared with dignity. “It is only right that those whose brains are dull and whose backs are strong should support in leisure those who can bring forth large thoughts and meditations. Has not this Hispan likewise its slaves—its Technicians and Workers —to bring the flower of Olgarchs like Gano and Beltan into being?”

Gano relaxed not a muscle of his face, but Beltan threw back his head and laughed. “By the hundred levels of Hispan, even in that early age the Greeks had learned the art of flattery. You are not quite right, friend Kleon. These are no slaves; these are but fixed castes of society, each with its duties firmly ordered. Hispan could not long exist without such strict, efficient subdivisions. Neither Workers nor Technicians are other than content with their lot.” He smiled bitterly. “That is left only as the last privilege of the Olgarchs.”

“Rather,” Gano interposed calmly, “it is your peculiar privilege, Beltan. No one else of our class feels the necessity for such a primitive emotion. Sometimes I think you are a sport, a mutant, not a true Olgarch.”

Sam turned to the head of the Olgarchs. “What,” he asked with a certain irony, “is the true function of the Olgarchs in this society of Hispan? The Technicians, I understand, supervise and create the scientific mechanism by which the city lives; the Workers lend their brawn and muscle to its functioning; but the Olgarchs?”

Gano frowned. “We live,” he answered sharply. “We are the reason for the creations of the Technicians, the labors of the Workers. We are the flower to which they are the roots and stems and leaves. They work, so that we may enjoy.”

Kleon nodded approvingly. “Hispan is not far apart from Athens,” he said. “There is much good in your system.”

Sam set his teeth. “That,” he declared, “has always been the rationalized justification for slavery, even to this future time. Has it ever occurred to you that the slaves—call them Technicians, Workers, Helots, what you will—would also like to live?”

“They are content, happy,” Gano answered softly. “Ask Tomson, if you will, whether this is not the best of all possible worlds.”

Beltan leaned forward. “Have you already forgotten, Sam Ward,” he mocked, “what you have told us of conditions in your own world? What were the Workers then if not slaves? Slaves who worked at the beck of others, who toiled far longer hours than the Workers of Hispan, who starved in times of depression and starved only more slowly while employed, who went to war to fight and kill for the benefit of others. Did you not have also your Technician class who toiled in laboratories and created new inventions for the benefit of your wealthy, your Olgarchs?”

“Yes, I suppose so,” Sam admitted unwillingly. “But at least they were free to work or not to work.”

“To starve, you mean.” Then, suddenly, the irony was gone from Beltan’s voice, and a certain fierce sincerity took its place. “It isn’t the plight of the Workers and Technicians that matters. They are well taken care of in Hispan; they do their work and are happy and content. No, it is the plight of the Olgarchs, the lords of Hispan, that matters most profoundly.

“Gano, here, at least has the illusion that he is performing a necessary function. The chief Technicians listen respectfully to his orders, obey them. But the city would flourish just the same if Gano never gave an order. As for the rest of us, we haven’t even that poor illusion. We sit and dawdle and wrap ourselves in fine garments, listen to fine music, eat delicate fare, strut and stroll and discuss in noble-sounding, empty phrases. We are parasites, aimless, unnecessary. We are excrescences on the body politic. The city could see us vanish and continue its course without a single jar.”

Gano was on his feet, his black brow clouded. “Beltan,” he said sharply, “even an Olgarch may go too far.”

Beltan’s nostrils quivered. There was defiance in his gaze. Then he subsided with a quizzical smile. “You are right, Gano,” he murmured. “Even an Olgarch may go too far.”

Kleon was puzzled. He was mightily taken with Beltan, but he did not understand his dissatisfaction. “If the uses of philosophy fail,” he interposed, “as they sometimes do, there is always the heady pursuit of war against the barbarian, the stranger.”

The young Olgarch said sadly: “There are no barbarians or strangers, unless it be you two. The city of Hispan is all that remains of the world.”

Sam gasped. “Do you mean that New York, London, Paris, the great countries, have been wiped out? How? Why?”

Beltan did not seem to see Gano’s frown, or seeing, paid no heed.

“The story,” he replied, “is not often told, and then only to Olgarchs. But since you already know about the once external world, there is no harm in telling it to you. Not long after your time, Sam Ward, in about the twenty-seventh century, the nations then existing had withdrawn more and more into their own boundaries. It was the logical, if mad development of tendencies in your own era. Nationalism, self-sufficiency, I believe, were the watchwords.

“The process accelerated, so our records report,” Beltan continued. “Soon even the national borders grew too large. The nationalistic tendencies, the patriotisms, grew fiercer, more local. Each nation, cut off from intercourse with other nations, bounded by impregnably fortified frontiers, dependent only on itself for its economy, found quarrels arising within its own confines. The fires of localism, of hatred for aliens, of patriotic fervor, finding nothing outside to feed upon, gnawed at their own vitals. Men of one community, a subdivision, a State, a city, decried the men of other communities, boasted of their superiority. They began to fight in internecine warfare.

“New nationalisms sprang up—nationalisms and hates based on smaller units. The countrysides became deserted, as the undefended farms and villages were devastated by the armies of opposing cities. The people collected in the towns, where there was a measure of protection. Soon the cry arose: New York for New Yorkers; London for the men of London; Paris for the Parisians!”

It was now Kleon’s turn to nod. Evolution, he reflected, was but an eternal recurrence. For what was this Olgarch of the future describing but Greece in the time of Pericles and the Peloponnesian War?

“Soon,” Beltan went on, “earth was broken up into a vast number of self-contained, heavily fortified cities. The old national boundaries were gone; newer and smaller ones took their place. Science advanced. Food was synthesized from inorganic elements; the secret of atomic power was discovered. The units grew smaller and smaller, drew away from each other. They fought, but the defenses were impregnable. The unfortified countryside became wholly deserted, unnecessary. It grew in the course of years into a tangle of wild forests, of desert stretches. All intercourse ceased. The cities rose vertically instead of horizontally along the earth, inclosed themselves in impassable barriers.

“Generation on generation added to these barriers, improved them with new methods of science. Such a one incloses Hispan, once a colony of your United States, now the sole survivor of all the teeming cities that once populated earth. A shield of neutron metal, impassable by any means known even to our science, was built up, layer on layer, around our city. No one knows how unimaginably thick it may be. No one has ever tried to penetrate its width.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Before The Golden Age»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Before The Golden Age» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Before The Golden Age» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.