These Dewey homes lure Issa’s attention when she isn’t on duty at the hospital. She finds new ones online every now and then, and rides past them on her bike. Sometimes she sees the other Dewey children. Quiet children who are alone. Loud, obnoxious children swarming the curb. She can’t see into their homes, but she can see how the light plays off the window shades when they move about within. Issa’s therapist says that her behavior makes sense. Issa wants to know if these kids are like her. As an adult, she is looking for patterns to know if her ways of relating with others developed differently as a child.

Her therapist says that they have, and that they come through in her bedside manner during her shifts. Like others who have grown up in the Dewey system, Issa’s speech patterns and mannerisms are more robotic—more “blinky.” Issa has a hard time trusting the faces that people make. She projects how she needs people to be, rather than letting them reveal how they actually are as human beings. Issa is also missing closure. She needs to go home again and shut the door behind her so that she can move forward, or the illusions of her past will follow her.

Now, Issa lingers at the mouth of the alley just before the door to her old home. The concrete is scrawled with pink and blue chalk and the cracks by the door are familiar. Being here feels to her like wearing an old pair of shoes that still fit.

Issa knocks.

“Just a minute!” Mom’s voice resounds from deep within and her heart leaps. There must be another child in there, perhaps Mackenzie’s younger brother or sister. She steps back, leans against a wall, and puts her hands in her pockets.

When the door opens, Mom’s neutral face greets her, a slight smile with two blush dots for cheeks.

“Hello, this is the Dewey home. Can I help you?”

Issa’s heart sinks.

“I… I’m sorry.” Issa speaks from her throat. “I must… I think I have the wrong address.”

Mom pulls a thinking face, question mark fading slowly in and out by her temple. “Issa?” Overjoyed face, now. Smiling eyes. “I’m sorry, sweetie, I must not have seen you for a second. Are you looking for Mackenzie? She’s at school.”

Issa breathes out fully, realizes she has been holding a portion of her breath this whole time. “Hi, Mom.” Her voice quavers. “That’s okay. I wanted to see you, too.”

Mom invites her in, but Issa declines. Seen from the outside, the kitchen is the same kitchen as before, but now seems to be just an arrangement of materials somehow. Issa peers down the hallway and can see how the Dewey home has been manufactured, easily deconstructed into an exploded view in her mind’s eye.

There’s another child inside. She can hear from the play sounds coming from the last bedroom that it’s a little boy. She realizes that this Dewey home is no longer just her past, but a continuum of pasts belonging to no single Dewey child entirely. Intruding might dispel what is now staged for that boy. He must need to believe in this as home, as she had.

They speak in the doorway about Mackenzie, Uncle Georg, and Trevor.

“Do you remember the party?” Issa does not.

Mom tells her to wait for a second. She goes back, retrieves something from the shady recesses of the storage, and returns with a piece of paper. It’s Issa’s drawing. The one that Mom had put up on the fridge.

“Are you still making art?”

“No. I work in the hospital now, actually. It’s not exactly a party, but there are birthdays.”

“I’m so glad!” Mom hugs Issa. Her plastics feel familiar and fragile and Issa can’t remember them ever having hugged each other at the same height. Mom’s chest warms up. The synthetic heartbeat patters bump-bump as it did before, but Issa pulls away.

There’s an awkward silence.

“Hey, Mom, will you give Mackenzie my new address? I’d like her to visit me, if that’s okay. I want her to know she can come over any time.”

“Of course, sweetie.”

“So… I should get back to work. My shift starts soon.”

“Issa-boo, wait! Before you go, can I ask you something?”

“Sure.”

Mom clasps her fingers together and her face changes to her hopeful face. “Was there anything I could have done to be a better Mom? Maybe something you wished I would have done differently?”

“Uh… I don’t….” Issa opens and closes her mouth, unsure of how to reply.

“How about on a scale of one to five? How many stars would you give me?”

WELCOME TO YOUR AUTHENTIC INDIAN EXPERIENCE™

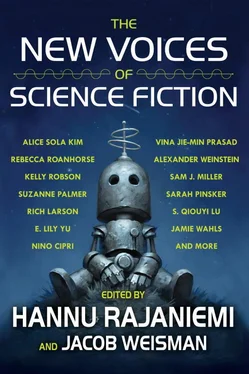

REBECCA ROANHORSE

Rebecca Roanhorse is a Black Ohkay Owingeh writer whose breakout novel Trail of Lightning was nominated for the 2019 Nebula and Hugo Awards for Best Novel. She won the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer in 2018.

“Welcome to Your Authentic Indian Experience™” was nominated for the Locus, Theodore Sturgeon Memorial, and World Fantasy awards, and it won the Hugo and Nebula awards. It confronts the concepts of authenticity and cultural experiences in the virtual-reality medium.

“In the Great American Indian novel, when it is finally written, all of the white people will be Indians and all of the Indians will be ghosts.”

—Sherman Alexie,

How to Write the Great American Indian Novel

YOU MAINTAIN A MENU of a half dozen Experiences on your digital blackboard, but Vision Quest is the one the Tourists choose the most. That certainly makes your workday easy. All a Vision Quest requires is a dash of mystical shaman, a spirit animal (wolf usually, but birds of prey are on the upswing this year), and the approximation of a peyote experience. Tourists always come out of the Experience feeling spiritually transformed. (You’ve never actually tried peyote, but you did smoke your share of weed during that one year at Arizona State, and who’s going to call you on the difference?) It’s all 101 stuff, really, these Quests. But no other Indian working at Sedona Sweats can do it better. Your sales numbers are tops.

Your wife Theresa doesn’t approve of the gig. Oh, she likes you working, especially after that dismal stretch of unemployment the year before last when she almost left you, but she thinks the job itself is demeaning.

“Our last name’s not Trueblood,” she complains when you tell her about your nom de rêve .

“Nobody wants to buy a Vision Quest from a Jesse Turnblatt,” you explain. “I need to sound more Indian.”

“You are Indian,” she says. “Turnblatt’s Indian-sounding enough because you’re already Indian.”

“We’re not the right kind of Indian,” you counter. “I mean, we’re Catholic, for Christ’s sake.”

What Theresa doesn’t understand is that Tourists don’t want a real Indian experience. They want what they see in the movies, and who can blame them? Movie Indians are terrific! So you watch the same movies the Tourists do, until John Dunbar becomes your spirit animal and Stands with Fists your best girl. You memorize Johnny Depp’s lines from The Lone Ranger and hang a picture of Iron Eyes Cody in your work locker. For a while you are really into Dustin Hoffman’s Little Big Man .

It’s Little Big Man that does you in.

For a week in June, you convince your boss to offer a Custer’s Last Stand special, thinking there might be a Tourist or two who want to live out a Crazy Horse Experience. You even memorize some quotes attributed to the venerable Sioux chief that you find on the internet. You plan to make it real authentic.

But you don’t get a single taker. Your numbers nosedive.

Management in Phoenix notices, and Boss drops it from the blackboard by Fourth of July weekend. He yells at you to stop screwing around, accuses you of trying to be an artiste or whatnot.

Читать дальше