“Fuck you,” Fletcher said, with his voice like gravel, and Sedgewick had never heard him say it or mean it until now.

He flopped back onto his bed, grasping for the slip-sliding anger as it trickled away in the dark. Shame came instead and sat at the bottom of him like cement. Minutes ticked by in silence. Sedgewick thought Fletcher was probably drifting to sleep already, probably not caring at all.

Then there was a bit-off sob, a sound smothered by an arm or a pillow, something Sedgewick hadn’t heard from his brother in years. The noise wedged in his ribcage. He tried to unhear it, tried to excuse it. Maybe Fletcher had peeled off his thermal and found frostbite. Maybe Fletcher was making a move, always another move, putting a lure into the dark between them and sharpening his tongue for the retort.

Maybe all Sedgewick needed to do was go and put his hand on some part of his brother, and everything would be okay. His heart hammered up his throat. Maybe. Sedgewick pushed his face into the cold fabric of his pillow and decided to wait for a second sob, but none came. The silence thickened into hard black ice.

Sedgewick clamped his eyes shut and it stung badly, badly.

ONE HOUR, EVERY SEVEN YEARS

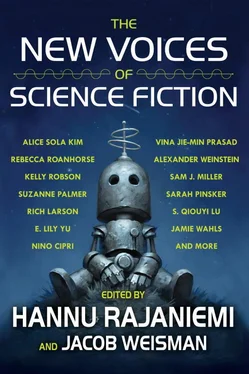

ALICE SOLA KIM

Alice Sola Kim has been published in Tin House , The Village Voice , McSweeney’s , Lenny , BuzzFeed Books , and Fantasy & Science Fiction . She received the prestigious Whiting Award in 2016 and has received grants and scholarships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Elizabeth George Foundation.

“One Hour, Every Seven Years” takes us through the life and times of a time-travel researcher trying to save her childhood self.

WHEN MARGOT IS NINE, she and her parents live on Venus. The surface of Venus, at that time, is one enormous sea with a single continent on its northern pole, perched there like a tiny, ridiculous top hat. There is sea below, and sea above, rain continually plummeting from the sky, endlessly self-renewing.

When I am thirty, I won’t have turned out so hot. No one will know; from a few feet away, I’ll seem fine. They won’t notice the dandruff, the opalescent flaking of my chin. They won’t know that I walk hard and deliberate, like a ’40s starlet in trousers, in order to compensate for the wobbly heels of my crummy shoes. They won’t see past my really great job. And it will be a great job, really. I will be working with time machines.

When Margot is nine, it has been five years since she has seen the sun. On Venus, the sun comes out but once every seven years. Margot’s family moved to Venus from Earth when she was four. This is the main thing that makes her different from her classmates, who are just a bunch of trashy Venus kids. Draftees and immigrants. Their parents work at the desalination plants, the dormitory facilities; they plumb and bail, they traverse Venus’s vast seas in ships and submersibles, and sometimes they do not come back.

To her classmates, Margot will never be Venusian, even though she’s her palest clammiest self like a Venusian, and walks and talks like a Venusian—with that lazy, slithering drawl. Why? First finger: she’s a freak, quiet and standoffish, but given to horrible bursts of loud friendliness that are so awkward, they make everyone hate her more for trying. Second finger: her dad is rich and powerful, but she still isn’t cool. The Venus kids don’t know it, but it isn’t her wealth they hate. It is the waste of it. The way her boring hair hangs against her fresh sweatshirts. The way she shuffles along in her blinding new sneakers. Third finger, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth fingers, and all the toes too: in her lifetime, Margot has seen the sun and they haven’t. Venus kids are strong and mean and easily offended. They know there’s a thing they should be getting that they’re not getting. And that the next best thing to getting something is no one in the whole world getting it.

When I am thirty, I will have gotten my first boyfriend. He’ll be a co-worker at the lab and I won’t have noticed him for the longest time. Big laugh, right? You would think that, as some nobody who nobody ever notices, I’d at least be the observant one by default, the one who notices everyone else and forms complex opinions about them, but, no, I will be a creature spiraled in upon myself, a shrimp with a tail curled into its mouth.

Late night at work, a group of people will be playing Jenga in the lounge. The researchers love Jenga because it has the destructive meathead glamour of sports but only a fraction of the physical peril. Anders will ask me if I want to play and I’ll shake my head, hoping it looks like I’m too cool for Jenga but also bemused and tolerant, all of this hiding the truth, which is that I am terrified of Jenga. I’m afraid of being the player who causes all of the blocks to fall. Because that player is both appreciated and despised: on the one hand they absorb the burden of causing the Fall, thus relieving everyone else of said burden, but on the other hand, they are responsible for ending the game prematurely, killing all the fun and potential, not to mention the Jenga tower itself—the spindly edifice that everyone worked so hard together to create and protect.

The guy who will be my first boyfriend will push a block out without any hesitation. He won’t poke at it first, he will go straight for the block, and I will watch as the tower wobbles. It won’t fall. As he takes the dislodged block and stacks it on his pile, he will make eye contact with me, a carefully constructed look of surprise on his face—mouth the shape of an O , eyebrows pushing his forehead into pleats.

When Margot is nine, the sun comes out on Venus. Her classmates lock her inside a closet and run away. They are gone for precisely one hour. When her classmates finally come back to let Margot out, it will be too late.

When I am thirty, I will have been at my great job, the job of working with time machines, long enough to learn their codes and security measures (I’ve even come up with a few myself), so I will do the thing that I didn’t even know I was planning to do all along. I will enter the time machine, emerging behind a desk in the school I attended when I was nine. Water droplets will condense on the walls. There is no way to keep out the damp on Venus. The air in the classroom will taste like the air in a bedroom where someone has just had a sweaty nightmare. I will hide during all of the ruckus, but don’t worry: I will work up the courage. I will stand and open the closet door and do what needs to be done. And I will return!

When Margot is nine, the sun comes out on Venus. Her classmates lock her inside a closet and run away. She hears someone moving outside. Margot’s throat is raw, but she readies another scream when the door opens. A golden woman stands in the doorway, her face dark, her hair edged with gilt. Behind her the sun shines through the windows like a fire, like a bombing the moment before everybody is dead. “Wouldn’t you like to play outside?” the woman says.

When I am thirty, I will live on Mars, the way I’ve always dreamed I would. I will live in the old condo alone, after my mother has moved out, and I will become a smoker the moment I find a pack my mother has left behind. It will feel wonderful to smoke on warm and dusty Martian nights. It will feel so good to blow smoke through the screen netting on the balcony and watch it swirl with the carmine dust. Many floors down, people will splash in the pool of the condo complex, all healthy and orange like they are sweating purified Beta Carotene and Vitamin C.

It is the sight of these party people that will spur me to spend a month attempting to loosen up and to get pretty. I will have a lot of time on my hands and a lot more money after my mother moves out. I will learn that there are lots of things you can do to fix yourself up, and that I hadn’t tried any of them. Makeup, as I learn it, is confusing and self-defeating. I’ll never understand why I have to make my face one flat uniform shade, only to add back color selectively until my old face is muffled and almost entirely muted: a quiet little cheep of itself. I will learn all of this from younger women at the department store, younger women who are better than me at covering up far nicer faces. I will also get some plastic surgery, because I will be extremely busy; I don’t have time to be painting this and patting that! I will have lost so much of my time already.

Читать дальше