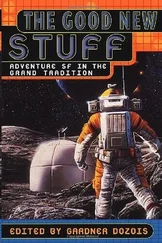

Гарднер Дозуа - The Good Old Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Гарднер Дозуа - The Good Old Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Good Old Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:0-312-19275-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good Old Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good Old Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good Old Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good Old Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A second pebble clattered off the pillar above my head. Another stung my body. I sprang away from the pillar. There was laughter and I ran.

There were infinities of streets, all glowing with color. There were many faces, strange faces, and robes blown out on a night wind, litters with scarlet curtains and beautiful cars like chariots drawn by beasts.

They flowed past me like smoke, without sound without substance, and the laughter pursued me, and I ran.

Four men of Shandakor came toward me. I plunged through them but their bodies opposed mine, their hands caught me and I could see their eyes, their black shining eyes, looking at me ....

I struggled briefly and then it was suddenly very dark.

The darkness caught me up and took me somewhere. Voices talked far away. One of them was a light young shiny sort of voice. It matched the laughter that had haunted me down the streets. I hated it.

I hated it so much that I fought to get free of the black river that was carrying me. There was a vertiginous whirling of light and sound and stubborn shadow and then things steadied down and I was ashamed of myself for having passed out.

I was in a room. It was fairly large, very beautiful, very old, the first place I had seen in Shandakor that showed real age—Martian age, that runs back before history had begun on Earth. The floor, of some magnificent somber stone the color of a moonless night, and the pale slim pillars that upheld the arching roof all showed the hollowings and smoothnesses of centuries. The wall paintings had dimmed and softened and the rugs that burned in pools of color on that dusky floor were worn as thin as silk.

There were men and women in that room, the alien folk of Shandakor.

But these breathed and spoke and were alive. One of them, a girl-child with slender thighs and little pointed breasts, leaned against a pillar close beside me. Her black eyes watched me, full of dancing lights.

When she saw that I was awake again she smiled and flicked a pebble at my feet.

I got up. I wanted to get that golden body between my hands and make it scream. And she said in High Martian, “Are you a human? I have never seen one before close to.”

A man in a dark robe said, “Be still, Duani.” He came and stood before me. He did not seem to be armed but others were and I remembered Conn’s little weapon. I got hold of myself and did none of the things I wanted to do.

“What are you doing here?” asked the man in the dark robe.

I told him about myself and Conn, omitting only the fight that he and I had had before he died, and I told him how the hillmen had robbed me.

“They sent me here,” I finished, “to ask for water.”

Someone made a harsh humorless sound. The man before me said, “They were in a jesting mood.”

“Surely you can spare some water and a beast!”

“Our beasts were slaughtered long ago. And as for water ...” He paused, then asked bitterly, “Don’t you understand? We are dying here of thirst!”

I looked at him and at the she-imp called Duani and the others. “You don’t show any signs of it,” I said.

“You saw how the human tribes have gathered like wolves upon the hills.

What do you think they wait for? A year ago they found and cut the buffed aqueduct that brought water into Shandakor from the polar cap.

All they needed then was patience. And their time is very near. The store we had in the cisterns is almost gone.”

A certain anger at their submissiveness made me say, “Why do you stay here and die like mice bottled up in a jar? You could have fought your way out. I’ve seen your weapons.”

“Our weapons are old and we are very few. And suppose that some of us did survive—tell me again, Earthman, how did Conn fare in the world of men?” He shook his head. “Once we were great and Shandakor was mighty. The human tribes of half a world paid tribute to us. We are only the last poor shadow of our race but we will not beg from men!”

“Besides,” said Duani softly, “where else could we live but in Shandakor?”

“What about the others?” I asked. “The silent ones.”

“They are the past,” said the dark-robed man and his voice rang like a distant flare of trumpets.

Still I did not understand. I did not understand at all. But before I could ask more questions a man came up and said, “Rhul, he will have to die.”

The tufted tips of Duani’s ears quivered and her crest of silver curls came almost erect.

“No, Rhul!” she cried. “At least not right away.”

There was a clamor from the others, chiefly in a rapid angular speech that must have predated all the syllables of men. And the one who had spoken before to Rhul repeated, “He will have to die! He has no place here. And we can’t spare water.”

“I’ll share mine with him,” said Duani, “for a while.”

I didn’t want any favors from her and said so. “I came here after supplies. You haven’t any, so I’ll go away again. It’s as simple as that.” I couldn’t buy from the barbarians, but I might make shift to steal.

Rhul shook his head. “I’m afraid not. We are only a handful. For years our single defense has been the living ghosts of our past who walk the streets, the shadows who man the walls. The barbarians believe in enchantments. If you were to enter Shandakor and leave it again alive the barbarians would know that the enchantment cannot kill. They would not wait any longer.”

Angrily, because I was afraid, I said, “I can’t see what difference that would make. You’re going to die in a short while anyway.”

“But in our own way, Earthman, and in our own time. Perhaps, being human, you can’t understand that. It is a question of pride. The oldest race of Mars will end well, as it began.”

He turned away with a small nod of the head that said kill him—as easily as that. And I saw the ugly little weapons rise.

There was a split second then that seemed like a year. I thought of many things but none of them were any good. It was a devil of a place to die without even a human hand to help me under. And then Duani flung her arms around me.

“You’re all so full of dying and big thoughts!” she yelled at them.

“And you’re all paired off or so old you can’t do anything but think! What about me? I don’t have anyone to talk to and I’m sick of wandering alone, thinking how I’m going to die! Let me have him just for a little while? I told you I’d share my water.”

On Earth a child might talk that way about a stray dog. And it is written in an old Book that a live dog is better than a dead lion. I hoped they would let her keep me.

They did. Rhul looked at Duani with a sort of weary compassion and lifted his hand. “Wait,” he said to the men with the weapons. “I have thought how this human may be useful to us. We have so little time left now that it is a pity to waste any of it, yet much of it must be used up in tending the machine. He could do that labor—and a man can keep alive on very little water.”

The others thought that over. Some of them dissented violently, not so much on the grounds of water as that it was unthinkable that a human should intrude on the last days of Shandakor. Conn had said the same thing.

But Rhul was an old man. The tufts of his pointed ears were colorless as glass and his face was graven deep with years and wisdom had distilled in him its bitter brew.

“A human of our own world, yes. But this man is of Earth and the men of Earth will come to be the new rulers of Mars as we were the old. And Mars will love them no better than she did us because they are as alien as we. So it is not unfitting that he should see us out.”

They had to be content with that. I think they were already so close to the end that they did not really care. By ones and twos they left as though already they had wasted too much time away from the wonders that there were in the streets outside. Some of the men still held the weapons on me and others went and brought precious chains such as the human slaves had worn—shackles, so that I should not escape. They put them on me and Duani laughed.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good Old Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.