Гарднер Дозуа - The Good Old Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Гарднер Дозуа - The Good Old Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, ISBN: 1998, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

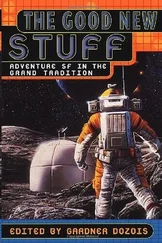

- Название:The Good Old Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:0-312-19275-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good Old Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good Old Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good Old Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good Old Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A good argument could be made, though, that by the mid-’60s the true home of Space Opera in the United States was not in any of the magazines anyway, but rather at Ace Books, especially the Ace Doubles line, which in addition to returning almost all of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s work to print, produced under the editorship of Donald A. Wollheim a long sequence of cheaply priced (affordable even to teenagers! A key point), garish-looking paperback editions of adventure books by Poul Anderson, John Brunner, Andre Norton, Jack Vance, Gordon R. Dickson, Tom Purdom, Kenneth Bulmer, G. C. Edmondson, Keith Laumer, A. Bertram Chandler, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Avram Davidson, and dozens of other authors—including, in the late ‘60s, innovative Space Opera work by brand-new writers such as Samuel R. Delany and Ursula K. Le Guin.

However, by the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, perhaps because of the prominence of the “New Wave” revolution in SF, which concentrated both on introspective, stylistically “experimental” work and work with more immediate sociological and political “relevance “ to the tempestuous social scene of the day (critics like Aldiss would call for more stories dealing with the Vietnam War, the “youth movement,” the ecology, the sexual revolution, the psychedelic scene, and so forth, while, in England, Michael Moorcock would utter his famous demand for work with “real drugs, real sex, really shocking ideas about society”), perhaps because of scientific proof that the other planets of the solar system were not likely abodes for life of any sort, let alone oxygen-breathing humanoid natives that you could have swordfights with and/or fall in love with, perhaps because the now more-widely-understood limitations of Einsteinian relativity had come to make even the less flamboyant idea of far-flung interstellar empires seem improbable at best (there were those, even SF writers, who said that the whole idea of interstellar flight itself was wishful nonsense, forget about interstellar empires!), science fiction as a genre was turning away from the Space Adventure tale, which now became even more outmoded and declassd than it had been before.

Stalwarts such as Poul Anderson and Jack Vance and Larry Niven continued to soldier on (and there would be one last seminal book published in the ‘60s, coming out right at the end of the decade, Samuel R. Delany’s Nova —a book which, although its influence was not immediately apparent, clearly had immense impact on the later Space Opera work of the new writers of the ‘80s and ‘90s), but there would be less Space Adventure stuff written in the following ten years or so than in any other comparable period in SF history. The generation of new writers who would come to prominence in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s would write almost none of it, for instance. By far the majority of work published during this period was set on Earth, often in the near future. Even the solar system had been largely deserted as a setting for stories, let alone the distant stars.

Not until the late ‘70s and early ‘80s would new writers such as John Varley, George R. R. Martin, Bruce Sterling, Michael Swanwick, and others, begin to grow interested in the Space Adventure again. By the ‘90s, a whole new boom in Baroque Space Opera would be underway, fueled by authors such as Iain M. Banks, Dan Simmons, Paul J. McAuley, Orson Scott Card, Vernor Vinge, Stephen Baxter, Stephen R. Donaldson, Alexander Jablokov, Charles Sheffield, Peter E Hamilton, and a dozen others, ushering in the third great Age of Space Opera.

But that’s clearly territory for The Good New Stuff . It became obvious that the natural breaking point for this volume was the beginning of the ‘70s, with the Space Adventure tale just about to fade into an interregnum. and that’s where I’ve ended it. The follow-up volume, The Good New Stuff , due out in January of 1999, will take up the story after the interregnum, in the mid-’70s.

It’s hard to deny that another of my major reasons for putting this anthology together was a nostalgic one. Just xeroxing the stories from crumbling old magazines and paperback collections, looking at the lurid covers and the garish pulp blurbs, having the cheap ink rub off on my fingers, smelling that curiously unique and instantly identifiable smell of old, brittle, yellowing paper, provided me with a nostalgic rush of such intensity that I was often able to remember where I was and what I was doing when I read the story for the first time thirty or more years before—and actually reading the stories again filled me with a much greater rush of images, outlandish settings, bizarre characters, strange creatures, odd concepts, vivid color, wild action.

But reading these stories again—as I had to read them over and over again to prepare this book for publication—I was struck by how well most of them hold up, even by today’s standards. There isn’t a story here that I wouldn’t buy today, if it were somehow crossing my desk for the first time.

So I don’t think that this book is merely an aging reader’s nostalgia trip, although it is inarguably also that. I think that these stories, like all good stories, are timeless. And I hope that this book—no doubt long out-of-print by then, sitting in a dusty heap in some secondhand book store, perhaps battered and coverless, waiting to be discovered by someone restless or bored enough to dust it off and pick it up—will still be offering its store of entertainment and wonder to new readers fifty years from now.

So sit back in a comfortable chair, break out the potato chips and ice cream (or a snifter of fine brandy, if you’d rather), and enjoy.

Few—if any—adventure stories ever written in any genre are better than the ones you are about to read, forged in the crucible of a market where stories competed with each other on the basis of how exciting they were, and didn’t get bought if they weren’t exciting.

This is the Good Old Stuff. Have fun.

—Gardner Dozois

The Rull

A. E. van Vogt

A. E. van Vogt was one of the first genre writers ever to publish an actual science fiction book, at a time when science fiction as a commercial publishing category did not yet exist, and almost all SF writers—even later giants such as Robert A. Heinlein—were able to publish novels only as serials in science fiction magazines. It’s indicative of the prestige and popularity that van Vogt could claim at the time that he was one of the first authors to whom publishers would turn when taking the first tentative steps toward establishing science fiction as a viable publishing category—which makes it all the more ironic that his work is all but forgotten today by most readers in the genre that he helped to shape.

Van Vogt’s stories were more complex, ornate, and recomplicated than the work of many of his predecessors from the Superscience days of the ‘30s—his most famous piece of writing advice is that you should throw a new idea into a story every five hundred words, a theory he seems to have consciously tried to apply in his own work. Van Vogt upped the stakes for Space Opera in the late ‘40s and early and mid-’50s with work like The Voyage of the Space Beagle, The Weapon Shops of Isher, The World of Null-A, Slan , and The War Against the Rull , increasing the Imagination Ante you had to come up with in order to sit down at the high-stakes table and play with the Big Boys, much as Alfred Bester and Jack Vance would do toward the end of the ‘50s, Cordwainer Smith and Frank Herbert would do in the mid-’60s, and Samuel R. Delany would do in the late ‘60s. Nobody, however, with the possible exception of the Bester of The Stars My Destination (who was himself clearly influenced by van Vogt), ever came close to mat ching van Vogt for headlong, breakneck pacing, or for the electric, crackling, paranoid tension with which he was capable of suffusing his work. as should be more than evident in the story that follows, which gives us one of the classic SF situations: a man pitted against an alien in a situation where there is no escape and to lose the struggle is to die, and where both adversaries are willing to do whatever it takes in order to win ...

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good Old Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good Old Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.