Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, ISBN: 2002, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

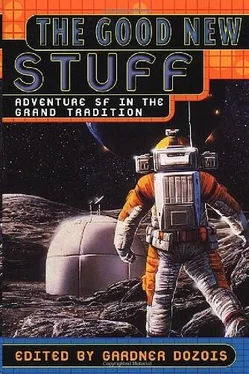

- Название:The Good New Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:0-312-26456-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good New Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good New Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good New Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good New Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This is not to say that there are no influences on his work. I think that recognizable traces of the influence of the work of writers such as Jack Vance, Cordwainer Smith, Brian W. Aldiss, Philip K. Dick, Howard Waldrop, Walter M. Miller, Jr., and Roger Zelazny can be seen in Swanwick's work, and perhaps even the influence of John Varley, although Varley started publishing only a few years before Swanwick himself did (influences turn over fast in the science fiction field!). Another big influence on Swanwick, as on Sterling, was clearly the early work of Samuel R. Delany; this is especially clear with the evocative story that follows, "The Blind Minotaur," which rings with strong echoes of Delany's work, particularly The Einstein Intersection— although, as always, Swanwick has changed the melody line and the orchestration and the fingering to make the material uniquely his own.

Although Swanwick's last few novels seem to be taking him away from science fiction (and perhaps even away from conventional genre fantasy toward that vaguely defined territory that might be described as "American Magic Realism," or perhaps "Postmodernism"), I don't think he will ever entirely abandon the field (at least some of his short fiction remains solidly centered here, and, in fact, falls under the heading of "hard science"), and it will be interesting to see what he produces the next time he returns to it at novel length. Like Sterling, Swanwick is also still a young writer by any reasonable definition, and I have a feeling he will be one of the factors shaping the evolution of SF well into the next century.

Swanwick's other books include the novella-length Griffin's Egg, one of the most brilliant and compelling of modern-day Moon-colony stories. His short fiction has been assembled in Gravity's Angels and in a collection of his collaborative short work with other writers, Slow Dancing Through Time. His most recent books are a collection of critical articles, The Postmodern Archipelago, and a new collection, A Geography of Unknown Lands. Swanwick lives in Philadelphia with his wife, Marianne Porter, and their son, Sean.

It was late afternoon when the blinded Minotaur was led through the waterfront. He cried openly, without shame, lost in his helplessness.

The sun cast shadows as crisp and black as an obsidian knife. Fisherfolk looked up from their nets or down from the masts of their boats, mild sympathy in their eyes. But not pity; memory of the Wars was too fresh for that. They were mortals and not subject to his tragedy.

Longshoremen stepped aside, fell silent at the passing of this shaggy bull-headed man. Offworld tourists stared down from their restaurant balconies at the serenely grave little girl who led him by the hand.

His sight stolen away, a new universe of sound, scent, and touch crashed about the Minotaur. It threatened to swallow him up, to drown him in its complexity.

There was the sea, always the sea, its endless crash and whisper on the beach, and quicker irregular slap at the docks. The sting of salt on his tongue. His callused feet fell clumsily on slick cobblestones, and one staggered briefly into a shallow puddle, muddy at its bottom, heated piss-warm by the sun.

He smelled creosoted pilings, exhaust fumes from the great shuttles bellowing skyward from the Starport, a horse sweating as it clipclopped by, pulling a groaning cart that reeked of the day's catch. From a nearby garage, there was the snap and ozone crackle of an arc-welding rig. Fishmongers' cries and the creaking of pitch-stained tackle overlaid rattling silverware from the terrace cafés, and fan-vented air rich with stews and squid and grease. And, of course, the flowers the little girl— was she really his daughter? — held crushed to her body with one arm. And the feel of her small hand in his, now going slightly slippery with sweat, but still cool, yes, and innocent.

This was not the replacement world spoken of and promised to the blind. It was chaotic and bewildering, rich and contradictory in detail. The universe had grown huge and infinitely complex with the dying of the light, and had made him small and helpless in the process.

The girl led him away from the sea, to the shabby buildings near the city's hot center. They passed through an alleyway between crumbling sheetbrick walls— he felt their roughness graze lightly against his flanks— and through a small yard ripe with fermenting garbage. The Minotaur stumbled down three wooden steps and into a room that smelled of sad, ancient paint. The floor was slightly gritty underfoot.

She walked him around the room. "This was built by expatriate Centaurimen," she explained. "So it's laid out around the kitchen in the center, my space to this side" — she let go of him briefly, rattled a vase, adding her flowers to those he could smell as already present, took his hand again—"and yours to this side."

He let himself be sat down on a pile of blankets, buried his head in his arms while she puttered about, raising a wall, laying out a mat for him under the window. "We'll get you some cleaner bedding in the morning, okay?" she said. He did not answer. She touched a cheek with her tiny hand, moved away.

"Wait," he said. She turned, he could hear her. "What— what is your name?"

"Yarrow," she said.

He nodded, curled about himself.

By the time evening had taken the edge off the day, the Minotaur was cried out. He stirred himself enough to strip off his loincloth and pull a sheet over himself, and tried to sleep.

Through the open window the night city was coming to life. The Minotaur shifted as his sharp ears picked up drunken laughter, the calls of streetwalkers, the wail of jazz saxophone from a folk club, and music of a more contemporary nature, hot and sinful.

His cock moved softly against one thigh, and he tossed and turned, kicking off the crisp sheet (it was linen, and it had to be white), agonized, remembering similar nights when he was whole.

The city called to him to come out and prowl, to seek out women who were heavy and slatternly in the tavernas, cool and crisp in white, gazing out from the balconies of their husbands' casavillas.

But the power was gone from him. He was no longer that creature that, strong and confident, had quested into the night. He twisted and turned in the warm summer air.

One hand moved down his body, closed about his cock. The other joined it. Squeezing tight his useless eyes, he conjured up women who had opened to him, coral-pink and warm, as beautiful as orchids. Tears rolled down his shaggy cheeks.

He came with great snorts and grunts.

Later he dreamed of being in a cool white casavilla by the sea, salt breeze wafting in through open windowspaces. He knelt at the edge of a bed and wonderingly lifted the sheet— it billowed slightly as he did— from his sleeping lover. Crouching before her naked body, his face was gentle as he marveled at her beauty.

It was strange to wake to darkness. For a time he was not even certain he was awake. And this was a problem, this unsureness, that would haunt him for all his life. Today, though, it was comforting to think it all a dream, and he wrapped the uncertainty around himself like a cloak.

The Minotaur found a crank recessed into the floor, and lowered the wall. He groped his way to the kitchen, and sat by the cookfire.

"You jerked off three times last night," Yarrow said. "I could hear you." He imagined that her small eyes were staring at him accusingly. But apparently not, for she took something from the fire, set it before him, and innocently asked, "When are you going to get your eyes replaced?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good New Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.