Ken Liu

THE HIDDEN GIRL AND OTHER STORIES

To my grandmother, Xiaoqian, who taught me how to tell stories.

And to Lisa, Esther, and Miranda, who showed me why stories are important.

There is a paradox at the heart of the art of fiction, at least as I’ve experienced it: while the medium of fiction is language, a technology whose primary purpose is communication, I can only write satisfying fiction by eschewing the communicative purpose.

An explanation. As the author, I construct an artifact out of words, but the words are meaningless until they’re animated by the consciousness of the reader. The story is co-told by the author and the reader, and every story is incomplete until a reader comes along and interprets it.

Each reader comes to the text with their own interpretive frameworks, assumptions about reality, background narratives concerning how the world is and ought to be. These are acquired through experience, through every individual’s unique history of encounters with irreducible reality. The plausibility of plot is judged against these battle-scars; the depth of characters is measured against these phenomenon-shadows; the truth vel non of each story is weighed with the fears and hopes residing in each heart.

A good story cannot function like a legal brief, which attempts to persuade and lead the reader down a narrow path suspended above the abyss of unreason. Rather, it must be more like an empty house, an open garden, a deserted beach by the ocean. The reader moves in with their own burdensome baggage and long-cherished possessions, seeds of doubt and shears of understanding, maps of human nature and baskets of sustaining faith. The reader then inhabits the story, explores its nooks and crannies, rearranges the furniture to suit their taste, covers the walls with sketches of their inner life, and thereby makes the story their home.

As an author, I find trying to build a house that would please every imagined future inhabitant limiting, constricting, paralyzing. Far better to construct a house in which I would feel at home, at peace, consoled by the sympathy between reality and the artifice of language.

Yet, experience has shown that it is when I am least aiming to communicate that the result is most open to interpretation; that it is when I am least solicitous of the comfort of my readers that they are mostly likely to make the story their home. Only by focusing purely on the subjective do I have a chance at achieving the intersubjective.

Picking the stories for this collection was thus, in more than one way, much easier than picking the stories for my debut, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories . Gone was the pressure to “present.” Rather than worrying about which stories would make the “best” collection for imaginary readers, I decided to stick with stories that most pleased myself. My editor, Joe Monti, was invaluable in this process and managed to weave the result into a table of contents that told a meta-narrative I couldn’t have seen myself.

May you find a story in here to make your home.

3.

NOVA PACIFICA, 2313

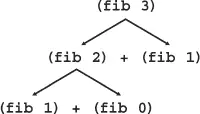

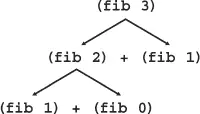

Ms. Coron pointed to the screen-board, on which she had typed out a bit of code.

(define (fib n)

(if (< n 2)

1

(+ (fib (− n 1)) (fib (− n 2)))))

“Let’s diagram the call-graph for this classic LISP function, which computes the n-th Fibonacci number recursively.”

Ona watched her Teacher turn around. The helmetless Ms. Coron wore a dress that exposed the skin of her arms and legs in a way that she had taught the children was beautiful and natural . Intellectually, Ona understood that the frigid air in the classroom, cold enough to give her and the other children hypothermia even with brief exposure, was perfectly suited to the Teachers. But she couldn’t help shivering at the sight. The airtight heat-suit scraped over Ona’s scales, and the rustling noise reverberated loudly in her helmet.

Ms. Coron went on, “A recursive function works like nesting dolls. To solve a bigger problem, a recursive function calls on itself to solve a smaller version of the same problem.”

Ona wished she could call on a smaller version of herself to solve her problems. She imagined that nested inside her was Obedient Ona, who enjoyed diagramming Classical Computer Languages and studying prosody in Archaic English. That would free her up to focus on the mysterious alien civilization of Nova Pacifica, the long-dead original inhabitants of this planet.

“What’s the point of studying dead computer languages, anyway?” Ona said.

The heads of the other children in the classroom turned as one to look at her, the golden glint from the scales on their faces dazzling even through the two layers of glass in their and Ona’s helmets.

Ona cursed herself silently. Apparently, instead of Obedient Ona, she had somehow called on Loudmouth Ona, who was always getting her in trouble.

Ona noticed that Ms. Coron’s naked face was particularly made up today, but her lips, painted bright red, almost disappeared into a thin line as she tried to maintain her smile.

“We study classical languages to acquire the habits of mind of the ancients,” Ms. Coron said. “You must know where you came from.”

The way she said “you” let Ona know that she didn’t mean just her in particular, but all the children of the colony, Nova Pacifica. With their scaled skin, their heat-tolerant organs and vessels, their six-lobed lungs—all engineered based on models from the local fauna—the children’s bodies incorporated an alien biochemistry so that they could breathe the air outside the Dome and survive on this hot, poisonous planet.

Ona knew she should shut up, but—just like the recursive calls in Ms. Coron’s diagram had to return up the call stack—she couldn’t keep down Loudmouth Ona. “I know where I came from: I was designed on a computer, grown in a vat, and raised in the glass nursery with the air from outside pumped in.”

Ms. Coron softened her voice. “Oh, Ona, that’s not… not what I meant. Nova Pacifica is too far from the home worlds, and they won’t be sending a rescue ship because they don’t know that we survived the wormhole and we’re stranded here on the other side of the galaxy. You’ll never see the beautiful floating islands of Tai-Winn or the glorious skyways of Pele, the elegant city-trees of Pollen, or the busy data warrens of Tiron—you’ve been cut off from your heritage, from the rest of humanity.”

Hearing—for the millionth time—these vague legends of the wonders that she’d been deprived of made the scales on Ona’s back stand up. She hated the condescension.

But Ms. Coron went on, “However, when you’ve learned enough to read the LISP source code that powered the first auto-constructors on Earth; when you’ve learned enough Archaic English to understand the Declaration of New Manifest Destiny; when you’ve learned enough Customs and Culture to appreciate all the recorded holos and sims in the Library— then you will understand the brilliance and elegance of the ancients, of our race.”

“But we’re not human! You made us in the image of the plants and animals living here. The dead aliens are more like us than you!”

Читать дальше