Mock chicken, vegetarian duck, papier-mâché houses, false money…

“Maybe we can go to see some opera performances in the streets later,” his father said, oblivious to William’s mood. “Just like when you were little.”

Forged bronzes…

He took out the two bubi from his pocket and placed them on the table, the gleaming side of the unfinished one facing up.

His father looked at them, paused for a moment, and then acted as if nothing was wrong. “You want to light the joss sticks?”

William said nothing, trying to find a way to phrase his question.

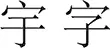

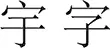

His father arranged the two bubi side by side and flipped them over. Carved into the patina on the reverse side of each was a character.

“The character forms from the Zhou Dynasty were a bit different from later forms,” his father said, as though William was still only a child being taught how to read and write. “So collectors from later ages would sometimes carve their interpretations of the script on the vessels. Like the patina, these interpretations also accumulate on the vessels in layers, build up over time.”

“Have you ever noticed how similar the character ‘jyu’—for the universe, which is also the first character in your name—is to the character ‘zi ’ —for writing?”

William shook his head, not really listening.

This entire culture is based on hypocrisy, on fakery, on mocking up the appearance for that which cannot be obtained.

“See how the universe is straightforward, but to understand it with the intellect, to turn it into language, requires a twist, a sharp turn? Between the World and the Word, there lies an extra curve. When you look at these characters, you’re convening with the history of these artifacts, with the minds of our ancestors from thousands of years ago. That is the deep wisdom of our people, and no Latin letters will ever get at our truth as deeply as our characters.”

William could no longer stand it. “You hypocrite! You are a forger!”

He waited, silently urging his father to deny the charge, to explain.

After a while, his father began to speak, not looking at him. “The first ghosts came to me a few years ago.”

He used the term gwailou for “foreigners,” but which also meant “ghosts.”

“They handed me antiques I had never seen before to restore. I asked them, ‘How did you get these?’ ‘Oh, we bought them from some French soldiers who conquered Peking and burned down the Palace and took these as loot.’

“For the ghosts, a robbery could give good title. This was their law. These bronzes and ceramics, handed down from our ancestors for a hundred generations, would now be taken from us and used to decorate the homes of robbers who did not even understand what they were. I could not allow it.

“So I made copies of the works I was supposed to restore, and I gave the copies back to the ghosts. The real artifacts I saved for this land, for you, and for your children. I mark the real ones and the copies with different characters, so that I can tell them apart. I know what I do is wrong in your eyes, and I am ashamed. But love makes us do strange things.”

Which is authentic? he thought. The World or the Word ? The truth or understanding?

The sound of a cane rapping against the front door interrupted them.

“Probably customers,” said his father.

“Open up!” whoever was at the door shouted.

William went to the front door and opened it, revealing a well-dressed Englishman in his forties, followed by two burly, scruffy men who looked like they were more at home in the docks of the colony.

“How do you do?” the Englishman said. Without waiting to be invited, he confidently stepped inside. The other two shoved William aside as they followed.

“Mr. Dixon,” his father said. “What a pleasant surprise.” His father’s heavily accented English made William cringe.

“Not as pleasant a surprise as the one you gave me, I assure you,” Dixon said. He reached inside his coat and pulled out a small porcelain figurine and set it on the table. “I gave you this to repair.”

“And I did.”

A smirk appeared on Dixon’s face. “My daughter is very fond of this piece. Indeed, it amuses me to see her treating the antique tomb figurine like a doll, and that was how it came to be broken. But after you returned the mended figurine, she refused to play with it, saying that it was not her dolly. Now, children are very good at detecting lies. And Professor Osmer was good enough to confirm my guess.”

His father straightened his back but said nothing.

Dixon gestured, and his two lackeys immediately shoved everything off the table: plates, dishes, bowls, the bubi , the food, the chopsticks—all crashed into a cacophonous heap.

“Do you want us to keep looking around? Or are you ready to confess to the police?”

His father kept his face expressionless. Inscrutable , the English would have called it. At the school, William had looked into a mirror until he had learned to not make that face, until he had stopped looking like his father.

“Wait a minute.” William stepped forward. “You can’t just go into someone’s house and act like a bunch of lawless thugs.”

“Your English is very good,” Dixon said as he looked William up and down. “Almost no accent.”

“Thank you,” William said. He tried to maintain a calm, reasonable tone and demeanor. Surely the man would realize now that he was not dealing with a common native family, but a young Englishman of breeding and good character. “I studied for ten years at Mr. George Dodsworth’s School in Ramsgate. Do you know it?”

Dixon smiled and said nothing, as though he was staring at a dancing monkey. But William pressed on.

“I’m certain my father would be happy to compensate you for what you feel you deserve. There’s no need to resort to violence. We can behave like gentlemen.”

Dixon began to laugh, at first a little, then uproariously. His men, confused at first, joined in after a while.

“You think that because you’ve learned to speak English, you are other than what you are. There seems to be something in the Oriental mind that cannot grasp the essential difference between the West and the East. I am not here to negotiate with you, but to assert my rights, a notion that seems foreign to your habits of mind. If you do not restore to me what is mine, we will smash everything in this place to smithereens.”

William felt the blood rush to his face, and he willed himself to let the muscles of his face go slack, to not betray his feelings. He looked across the room at his father, and suddenly he realized that his father’s expression must also be his expression, the placid mask over a helpless rage.

While they talked, his father had been slowly moving behind Dixon. Now he looked over at William, and the two nodded at each other almost imperceptibly.

And therfore I wole leve al that thing that I can think, and chese to my love that thing that I cannot think.

William jumped at Dixon as his father lunged at Dixon’s legs. The three men fell to the ground in a heap. In the struggle that followed, William seemed to observe himself from a distance. There was no thought, but a mixture of love and rage that clouded his mind until William found himself sitting astride Dixon’s prone body, clutching one of the bubi , poised to smash its blade into Dixon’s head.

The two men Dixon had brought with him looked on helplessly, frozen in place.

Читать дальше