"Once some guys attacked me on the street," Phil said one chilly evening after class as we pulled on street clothes and gathered our gear at the picnic table. "One of them threw a Coke bottle. I blocked automatically. The bottle shattered against my left forearm—still a few slivers in there—and the pieces flew off to the side. It was rather spectacular. I must have looked as if I knew what I was doing, because they backed off."

"Sounds like rejecting the attack rather than turning with it," I suggested.

"Yes, it was," he agreed. "Everything you know in the martial arts eventually flows together. What you're left with is your own style. You will do what is most appropriate."

Phil died on Monday, February 26, 1990, of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, at the typical rate. It had eroded him for about two years. He turned with it, embracing the attacks and putting forth the best responses he could to each of its grapplings, with his own diminishing energies. He did block and punch, too; he did push and pull. But he had no choice but to enter its universe, to play by its rules. I taught his classes, under his guidance, during that time— and later by general consent of the class itself when he was no longer able to come in, periodically reporting back to him by telephone and seeking advice. I continued the teaching for several years after that, also.

He was buried in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on Thursday, March 1. He was survived by an amazing lady, Karen, a lovely daughter from a previous marriage, Carissa, and by all of those whom he had taught. Leroy Yerxa, Jr., Jamii Corley (herself an aikido, kenjutsu, and aikijutsu sensei ), Claudia Hallowell, and I were at the service and the graveside with the family. Donna Lubell (a karate sensei ) was there in spirit, as were some of the others I could not reach in time, or who could not travel the distance.

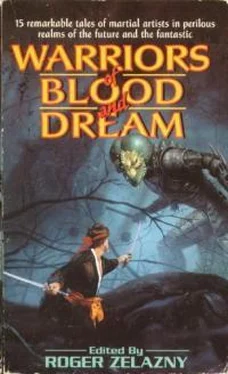

I wanted to open with a pair of tales representing

the yang and the yin of martial arts —

and they

don't come much yanger than this one.

Damn !

this man's a vivid writer.

Master of Misery

Joe R. Lansdale

To the memory of my father, Bud Lansdale

Six o'clock in the morning, Richard was crossing by ferry from the Hotel on the Cay to Christiansted with a few other early-bird tourists, when he turned, looked toward shore, and saw a large ray leap from the water, its blue-gray hide glistening in the morning sunlight like gunmetal, its devil-tail flicking to one side as if to slash.

The ray floated there in defiance of gravity, hung in the sky between the boat and the shore, backgrounded by the storefronts and dock as if it were part of a painting, then splashed almost silently into the purple Caribbean, leaving in its wake a sun-kissed ripple.

Richard turned to see if the other passengers had noticed. He could tell from their faces they had not. The ray's leap had been a private showing, just for him, and he relished it. Later, he would think that perhaps it had been some kind of omen.

Ashore, he walked along the dock past the storefronts, and in front of the Anchorinn Restaurant, the charter fishing boat was waiting.

A man and a woman were on board already. The man was probably fifty, perhaps a little older, but certainly in good shape. He had an aura of invincibility about him, as if the normal laws of mortality and time did not apply to him.

He was about five-ten with broad shoulders, and, though he was a little thick in the middle, it was a hard thickness. It was evident, even beneath the black, loose, square-cut shirt he was wearing, he was a muscular man, perhaps first by birth, and second by exercise. His skin was as dark and leathery as an old bull's hide, his hair like frost on scorched grass. He was wearing khaki shorts and his dark legs were corded with muscle and his shins had a yellow shine to them that brought to mind weathered ivory.

He stood by the fighting chair bolted to the center of the deck, and looked at Richard standing on the dock with his little paper bag containing lunch and suntan lotion. The man's crow-colored eyes studied Richard as if he were a pile of dung that might contain some kernel of rare and undigested corn a crow might want.

The man's demeanor bothered Richard immediately. There was about him a cockiness. A way of looking at you and sizing you up and letting you know he wasn't seeing much.

The woman was quite another story. She was very much the bathing beauty type, aged beyond competition, but still beautiful, with a body by Nautilus. She was at least ten years younger than the man. She wore shoulder-length blond hair bleached by sun and chemicals. She had a heart-shaped face and a perfect nose and full lips. There was a slight cleft in her chin and her eyes were a faded blue. She was willowy and big breasted and wore a loose, white tee shirt over her black bathing suit, one of the kind you see women wear in movies, but not often on the beach. She had the body for it. A thong, or string, Richard thought the suits were called. Sort of thing where the strap in the back slid between the buttocks and covered them not at all. The top of the suit made a dark outline beneath her white tee shirt. She moved her body easily, as if she were accustomed to and not bothered by scrutiny, but there was something about her eyes that disturbed Richard.

Once, driving at night, a cat ran out in front of his car and he hit it, and when he stopped to see if there was hope, he found the cat mashed and dying, the eyes glowing hot and savage and terrified in the beam of his flashlight. The woman's eyes were like that.

She glanced at him quickly, then looked away. Richard climbed on board.

Richard extended his hand to the older man. The man smiled and took his hand and shook it. Richard cursed himself as the man squeezed hard. He should have expected that. "Hugo Peak," the older man said, then moved his head to indicate the woman behind him. "My wife, Margo."

Margo nodded at Richard and almost smiled. Richard was about to give his name, when the captain, Bill Jones, came out of the cabin grinning. He was a lean weathered fellow with a face that was all nose and eyes the color of watered meat gravy. He was carrying a couple cups of coffee. He gave one to Margo, the other to Hugo. He said, "Richard, how are you, my man?"

"Wishing I'd stayed in bed," Richard said. "I can't believe I let you talk me into this, Jones."

"Hey, fishing's not so bad," said the captain.

"Off the bank at home in Texas it might be all right. But all this water. I hate it."

This was true. Richard hated the water. He could swim, had even earned lifeguard credentials as a Boy Scout, some twenty-five years ago, back when he was thirteen, but he had never learned to like the water. Especially deep water. The ocean.

He realized he had let Jones talk him into this simply because he wanted to convince himself he wasn't phobic. So, okay, he wasn't phobic, but he still didn't like the water. The thought of soon being surrounded by it, and it being deep, and above them there being nothing but hot blue sky, was not appealing.

"I'll get you some coffee and we'll shove off," Jones said.

"I thought it took five for a charter?" Richard said.

Jones looked faintly embarrassed. "Well, Mr. Peak paid the slack. He wanted to keep it down to three. More time in the chair that way, we hit something."

Richard turned to Peak. "I suppose I should split the difference with you."

"Not at all," Peak said. "It was my idea."

"That's kind of you, Hugo," Richard said.

"Not at all. And if it doesn't sound too presumptuous, I don't much prefer to be called by my first name, unless it's by my wife. If I'm not fucking the person, I want them to call me Mr. Peak. Or Peak. That all right with you?"

Читать дальше