"Contemporary Ceramics," her husband said, relishing the syllables. "A fine boy, Bud. A pleasure to have him for a boarder."

"After thirty years spent in these studies," the stranger, who had continued to speak unnoticed, went on, "he turned from the theoretical to the pragmatic. In ten years’ time he had made the most titanic discovery in history: he made mankind, all mankind, superfluous; he made me. "

"What did Tillie write in her last letter?" asked the old man.

The old woman shrugged.

"What should she write? The same thing. Sidney was home from the Army, Naomi has a new boyfriend—"

" He made ME! "

"Listen, Mr. Whatever-your-name-is," the old woman said, "maybe where you came from is different, but in this country you don’t interrupt people while they’re talking… Hey. Listen—what do you mean, he made you? What kind of talk is that?"

The stranger bared all his teeth again, exposing the too-pink gums.

"In his library, to which I had a more complete access after his sudden and as yet undiscovered death from entirely natural causes, I found a complete collection of stories about androids, from Shelley’s Frankenstein through Capek’s R.U.R. to Asimov’s—"

"Frankenstein?" said the old man with interest. "There used to be a Frankenstein who had the soda- wasser place on Halstead Street—a Litvack, nebbich. "

"What are you talking?" Mrs. Gumbeiner demanded. "His name was Franken thal, and it wasn’t on Halstead, it was on Roosevelt."

"—clearly shown that all mankind has an instinctive antipathy towards androids and there will be an inevitable struggle between them—"

"Of course, of course!" Old Mr. Gumbeiner clicked his teeth against his pipe. "I am always wrong, you are always right. How could you stand to be married to such a stupid person all this time?"

"I don’t know," the old woman said. "Sometimes I wonder, myself. I think it must be his good looks." She began to laugh. Old Mr. Gumbeiner blinked, then began to smile, then took his wife’s hand.

"Foolish old woman," the stranger said. "Why do you laugh? Do you not know I have come to destroy you?"

"What?" old Mr. Gumbeiner shouted. "Close your mouth, you!" He darted from his chair and struck the stranger with the flat of his hand. The stranger’s head struck against the porch pillar and bounced back.

"When you talk to my wife, talk respectable, you hear?"

Old Mrs. Gumbeiner, cheeks very pink, pushed her husband back to his chair. Then she leaned forward and examined the stranger’s head. She clicked her tongue as she pulled aside a flap of grey, skinlike material.

"Gumbeiner, look! He’s all springs and wires inside!"

"I told you he was a golem, but no, you wouldn’t listen," the old man said.

"You said he walked like a golem. "

"How could he walk like a golem unless he was one?"

"All right, all right… You broke him, so now fix him."

"My grandfather, his light shines from Paradise, told me that when MoHaRal—Moreynu Ha-Rav Löw—his memory for a blessing, made the golem in Prague, three hundred? four hundred years ago? he wrote on his forehead the Holy Name."

Smiling reminiscently, the old woman continued, "And the golem cut the rabbi’s wood and brought his water and guarded the ghetto."

"And one time only he disobeyed the Rabbi Löw, and Rabbi Löw erased the Shem Ha-Mephorash from the golem ‘s forehead and the golem fell down like a dead one. And they put him up in the attic of the shule, and he’s still there today if the Communisten haven’t sent him to Moscow… This is not just a story," he said.

" Avadda not!" said the old woman.

"I myself have seen both the shule and the rabbi’s grave," her husband said conclusively.

"But I think this must be a different kind of golem, Gumbeiner. See, on his forehead; nothing written."

"What’s the matter, there’s a law I can’t write something there? Where is that lump of clay Bud brought us from his class?"

The old man washed his hands, adjusted his little black skull-cap, and slowly and carefully wrote four Hebrew letters on the grey forehead.

"Ezra the Scribe himself couldn’t do better," the old woman said admiringly. "Nothing happens," she observed, looking at the lifeless figure sprawled in the chair.

"Well, after all, am I Rabbi Löw?" her husband asked deprecatingly. "No," he answered. He leaned over and examined the exposed mechanism. "This spring goes here… this wire comes with this one…" The figure moved. "But this one goes where? And this one?"

"Let be," said his wife. The figure sat up slowly and rolled its eyes loosely.

"Listen, Reb Golem, " the old man said, wagging his finger. "Pay attention to what I say—you understand?"

"Understand…"

"If you want to stay here, you got to do like Mr. Gumbeiner says."

"Do-like-Mr.-Gumbeiner-says…"

" That’s the way I like to hear a golem talk. Malka, give here the mirror from the pocketbook. Look, you see your face? You see the forehead, what’s written? If you don’t do like Mr. Gumbeiner says, he’ll wipe out what’s written and you’ll be no more alive."

"No-more-alive…"

" That’s right. Now, listen. Under the porch you’ll find a lawnmower. Take it. And cut the lawn. Then come back. Go."

"Go…" The figure shambled down the stairs. Presently the sound of the lawnmower whirred through the quiet air in the street just like the street where Jackie Cooper shed huge tears on Wallace Beery’s shirt and Chester Conklin rolled his eyes at Marie Dressler.

"So what will you write to Tillie?" old Mr. Gumbeiner asked.

"What should I write?" old Mrs. Gumbeiner shrugged. "I’ll write that the weather is lovely out here and that we are both, Blessed be the Name, in good health."

The old man nodded his head slowly, and they sat together on the front porch in the warm afternoon sun.

(1955)

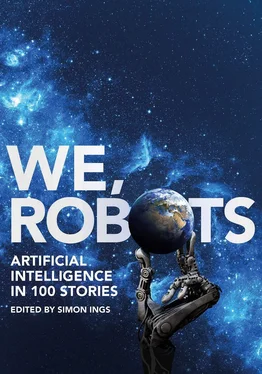

NON-FICTION

Dustin A. Abnet, The American Robot: A Cultural History , 2020, University of Chicago Press

Minsoo Kang, Sublime Dreams of Living Machines: The automaton in the European imagination , 2011, Harvard University Press

Mateo Kries et al., Hello Robot: Design between human and machine , 2017, Vitra Design Museum

Stanisław Lem (trans. Joanna Zylinska), Summa Technologiae , [1964] 2014, University of Minnesota Press

Adrienne Mayor, Gods and Robots: Myths, machines and ancient dreams of technology , 2018, Princeton University Press

Chloe Wood (ed.), AI: More than Human , 2019, Barbican International Enterprises

Gaby Wood, Living Dolls: A magical history of the quest for mechanical life , 2002, Faber

FICTION

David R. Bunch, Moderan , [1971] 2018, NYRB Classics

Samuel Butler, Erewhon, [1872] 2006, Penguin Classics; New Impression edition

Karel Capek (trans. Claudia Novack-Jones), R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) , [1921] 2004, Penguin Classics

John Sladek, Tik-Tok , 1983, Corgi

Stanisław Lem (trans. Michael Kandel), The Cyberiad – fables for the cybernetic age , [1975] 2020, MIT Press

Auguste Villiers de l’Isle-Adam (trans. Robert Martin Adams), Tomorrow’s Eve , [1886] 2000, University of Illinois Press

Rachilde (trans. Melanie Hawthorne), Monsieur Venus , [1884] 2004, Modern Language Association

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Or the Modern Prometheus , [1818] 2003, Penguin Classics

Читать дальше