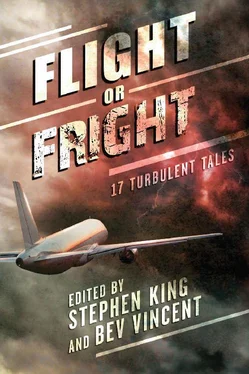

FLIGHT OR FRIGHT

Edited by

Stephen King

and Bev Vincent

This anthology is dedicated to all the pilots, real and fictional, who landed their planes after a harrowing flight and brought their passengers home safely. The list includes:

Wilbur Wright

Chesley Sullenberger

Tammie Jo Shults

Vernon Demerest

Robert Pearson

Eric Gennotte

Tim Lancaster

Min-Huan Ho

Eric Moody

Peter Burkill

Bryce McCormick

Robert Schornstheimer

Richard Champion de Crespigny

Robert Piché

Brian Engle

Ted Striker

Introduction

Stephen King

Are there people in this modern, technology-driven world who enjoy flying? Hard as it might be to believe, I’m sure there are. Pilots do, most children do (although not babies; the changes in air pressure messes them up), assorted aeronautical enthusiasts do, but that’s about it. For the rest of us, commercial air travel has all the charm and excitement of a colorectal exam. Modern airports tend to be overcrowded zoos where patience and ordinary courtesy are tested to the breaking point. Flights are delayed, flights are canceled, luggage is tossed around like beanbags, and on many occasions does not arrive with passengers who desperately desire clean shirts or even just one set of fresh underwear.

If you have an early morning flight, God help you. It means rolling out of bed at four in the morning so you can go through a check-in and boarding process as convoluted and tension-inducing as getting out of a small and corrupt South American country in 1954. Do you have a photo ID? Have you made sure your shampoo and conditioner are in small plastic see-thru bottles? Are you prepared to lose your shoes and have your various electronic gadgets irradiated? Are you sure nobody else packed your luggage, or had access to it? Are you ready to undergo a full body scan, and perhaps a pat-down of your naughty bits for good measure? Yes? Good. But you still may discover that your flight has been overbooked, delayed by mechanical or weather issues, perhaps canceled because of a computer meltdown. Also, heaven help you if you’re flying standby; you might have better luck buying a lottery scratch ticket.

You surmount these hurdles so you can enter what one of the contributors to this anthology refers to as “a howling shell of death.” Isn’t that a bit over the top, you might ask, not to mention contrary to fact? Granted. Airliners rarely flame out (although we’ve all seen unsettling cell phone footage of engines belching fire at 30,000 feet), and flying rarely results in death (statistics say you’re more likely to be killed crossing the street, especially if you’re a damn fool peering at your cell phone while you do it). Yet you are entering what is basically a tube filled with oxygen and sitting atop tons of highly flammable jet fuel.

Once your tube of metal and plastic is sealed up (like—gulp!—a coffin) and leaving the runway, trailing its dwindling shadow behind it, only one thing is sure, a thing so positive it is beyond statistics: you will come down. Gravity demands it. The only question is where and why and in how many pieces, one being the ideal. If the reunion with mother earth is on a mile of concrete (hopefully at your destination, but any mile of paved surface will do in a pinch), all is well. If not, your statistical chances of survival plummet rapidly. That, too, is a statistical fact, and one even the most seasoned air travelers must contemplate when their flight runs into clear air turbulence at 30,000 feet.

You’re completely out of control at such moments. You can do nothing constructive except double-check your seatbelt as the plates and bottles rattle in the galley and overhead bins pop open and babies wail and your deodorant gives up and the flight attendant comes on the overhead speakers, saying “The captain asks that you remain seated.” While your overcrowded tube rocks and rolls and judders and creaks, you have time to reflect on the fragility of your body and that one irrefutable fact: you will come down.

Having thus prepared you with food for thought on your next trip through the sky, let me ask the appropriate question: is there any human activity, any at all, more suited to an anthology of horror and suspense stories like the one you now hold in your hands? I think not, ladies and gentlemen. You have it all: claustrophobia, acrophobia, loss of volition. Our lives always hang by a thread, but that is never more clear than when descending into LaGuardia through thick clouds and heavy rain.

On a personal note, your editor is a much better flier than he used to be. Thanks to my career as a novelist, I have flown a great deal over the last forty years, and until 1985 or so, I was a very frightened flier indeed. I understood the theory of flight, and I understood all the safety stats, but neither of those things helped. Part of my problem came from a desire (which I still have) to be in control of every situation. I feel safe when I’m behind the wheel, because I trust myself. When you’re behind the wheel…not quite so much (sorry about that). When you enter an airplane and sit down, you are surrendering control to people you don’t know; people you may never even see.

Worse, for me, is the fact that I have honed my imagination to a keen edge over the years. That’s fine when I’m sitting at my desk and concocting tales where terrible things may happen to very nice people, not so fine when I’m being held hostage in an airplane that turns onto the runway, hesitates, then bolts forward at speeds that would be considered beyond suicidal in the family car.

Imagination is a double-edged blade, and in those early days when I began doing a great deal of flying for my work, it was all too easy to cut myself with it. All too easy to fall into thoughts of all the moving parts in the engine outside my window, so many parts it seemed almost inevitable for them to fall into disharmony. Easy to wonder—impossible not to, really—what every little change in the sound of those engines might mean, or why the plane suddenly tilted in a new direction, the surface of my Pepsi tilting with it (alarmingly!) in its little plastic glass.

If the pilot walked back to have a little chinwag with the passengers, I wondered if the co-pilot was competent (surely he couldn’t be as competent, or he wouldn’t be the redundancy feature). Maybe the plane was on autopilot, but suppose the autopilot suddenly kicked off while the pilot was discussing the chances of the Yankees with someone, and the plane went into a sudden dive? What if the luggage bay latches let go? What if the landing gear froze? What if a window, defective but passed by a quality control employee dreaming about his honey back home, blew out? For that matter, what if a meteor hit us, and the cabin depressurized?

Then, in the mid-eighties, most of those fears subsided, thanks to having a near-death experience while climbing out of Farmingdale Airport in New York, on my way to Bangor, Maine. I’m sure there are plenty of people out there—some perhaps reading this book right now—who have had their own air-scares, everything from collapsing nose gear to planes sliding off icy runways, but this was as close to death as it is possible to come and still live to tell about it.

It was late afternoon. The weather was as clear as a bell. I had chartered a Lear 35, which on takeoff was like having a rocket strapped to your ass. I had been on this particular Lear many times. I knew and trusted the pilots, and why not? The one in the left-hand seat had started flying jets in Korea, had survived scores of combat missions there, and had been flying ever since. He had tens of thousands of hours. I got out my paperback novel and my book of crosswords, anticipating a smooth flight and a pleasant reunion with my wife, kids, and the family dog.

Читать дальше