“Margaret, you are my wife!” Willy Jones gasped.

“Am I of an age to be your wife?” she jibed. “Regard me! Of what age do I seem to be?”

“Of the same age as when I left,” said Willy. “But perhaps you have eaten of the besok nut and so do not change your appearance.”

“I forgot to tell you about the besok nut,” said Galli. “If one eats the nut of the besok tree, the tomorrow tree, the time tree, that one will not age. But this is always accompanied by a chilling unhappiness.”

“Perhaps I did eat it,” said Margaret. “But that is my grave there, and I have lain in it many years, as has she. You are prohibited from touching either of us.”

“Are you the mother or the daughter, Witch?”

“You will never know. You will see us both, for we take turns, and you will not be able to tell us apart. See, the grave is always disturbed, and the entrance is easy.”

“I’ll have the truth from the golem who served you while I was gone,” Willy swore.

“A golem is an artificial man,” said Galli. “They were made by the Jews and Arabs in earlier ages, but now they say that they have forgotten how to make them. I wonder that you do not make them yourselves, for you have advanced techniques. You tell them and you picture them in your own heroic literature,” (he patted the comic books under his arm), “but you do not have them in actuality.”

The golem told Willy Jones that the affair was thus:

A daughter had indeed been born to Margaret. She had slain the child, and had then put it into the middle state. Thereafter, the child stayed sometimes in the grave, and sometimes she walked about the island. And she grew as any other child would. And Margaret herself had eaten the besok nut so that she would not age.

When mother and daughter had come to the same age and appearance (and it had only been the very day before that, the day before Willy Jones had returned), then the daughter had also eaten the besok nut. Now the mother and daughter would be of the same appearance forever, and not even a golem could tell them apart.

Willy Jones came furiously onto the woman again.

“I was sure before, and now I am even more sure that you are Margaret,” he said, “and now I will have you in my fury.”

“We both be Margaret,” she said. “But I am not the same one you apprehended earlier. We changed places while you talked to the golem. And we are both in the middle state, and we have both been dead in the grave, and you dare not touch either of us ever. A Welshman turned Dutchman turned Malayan turned Jilolo has this spook in him four times over. The Devil himself will not touch his own daughters.”

The last part was a lie, but Willy Jones did not know it.

“We be in confrontation forever then,” said Willy Jones. “I will make my Big House a house of hate and a house of skulls. You cannot escape from its environs, neither can any visitor. I’ll kill them all and pile their skulls up high for a monument to you.”

Then Willy Jones ate a piece of bitter bark from the pokok ru.

“I forgot to tell you that when a person eats bark from the pokok ru in anger, his anger will sustain itself forever,” Galli said.

“If it’s visitors you want for the killing, I and my mother-daughter will provide them in numbers,” said Margaret. “Men will be attracted here forever with no heed for danger. I will eat a telor tuntong of the special sort, and all men will be attracted here even to their death.”

“I forgot to tell you that if a female eats the telor tuntong of the special sort, all males will be attracted irresistibly,” Galli said. “Ah, you smile as though you doubted that the besok nut or the bark of the pokok ru or the telor tuntong of the special sort could have such effects. But yourselves come now to wonder drugs like little boys. In these islands they are all around you and you too blind to see. It is no ignorant man who tells you this. I have read the booklets from your orderly tents: Physics without Mathematics, Cosmology without Chaos, Psychology without Brains . It is myself, the master of all sciences and disciplines, who tells you that these things do work. Besides hard science, there is soft science, the science of shadow areas and story areas, and you do wrong to deny it the name.

“I believe that you yourself can see what had to follow, from the dispositions of the Margarets and Willy Jones,” Galli said. “For hundreds of years, men from everywhere came to the Margarets who could not be resisted. And Willy Jones killed them all and piled up their skulls. It became, in a very savage form, what you call the Badger Game.”

Galli was a good-natured and unhandsome brown man. He worked around the army base as translator, knowing (besides his native Jilolo), the Malayan, Dutch, Japanese, and English languages, and (as every storyteller must) the Arabian. His English was whatever he wanted it to be, and he burlesqued the speech of the American soldiers to the Australians, and the Australians to the Americans.

“Man, it was a Badger!” the man said. “It was a grizzle-haired, glare-eyed, flat-headed, underslung, pigeon-toed, hook-clawed, clam-jawed Badger from Badger Game Corner! They moved in on us, but I’d take my chances and go back and do it again. We hadn’t frolicked with the girls for five minutes when the things moved in on us. I say things; I don’t know whether they were men or not. If they were, they were the coldest three men I ever saw. But they were directed by a man who made up for it. He was livid, hopping with hatred. They moved in on us and began to kill us.”

No, No, that isn’t part of Galli’s story. That’s some more of the ramble that the fellow told me in the bar the other evening.

It has been three hundred years, and the confrontation continues. There are skulls of Malayan men and Jilolo men piled up there; and of Dutchmen and Englishmen and of Portuguese men; of Chinamen and Filipinos and Goanese; of Japanese, and of the men from the United States and Australia.

“Only this morning there were added the skulls of two United States men, and there should have been three of them,” Galli said. “They came, as have all others, because the Margarets ate the telor tuntong of the special sort. It is a fact that with a species (whether insect or shelled thing or other) where the male gives his life in the mating, the female has always eaten of this telor tuntong. You’d never talk the males into such a thing with words alone.”

“How is it that there were only two United States skulls this morning, and there should have been three?” I asked him.

“One of them escaped,” Galli explained, “and that was unusual. He fell through a hole to the middle land, that third one of them. But the way back from the middle land to one’s own country is long, and it must be walked. It takes at least twenty years, wherever one’s own country is; and the joker thing about it is that the man is always wanting to go the other way.

“That is the end of the story, but let it not end abruptly,” Galli said. “Sing the song Chari Yang Besar if you remember the tune. Imagine about flute notes lingering in the air.”

“I was lost for more than twenty years, and that’s a fact,” the man said. He gripped the bar with the most knotted hands I ever saw, and laughed with a merriment so deep that it seemed to be his bones laughing. “Did you know that there’s another world just under this world, or just around the corner from it? I walked all day every day. I was in a torture, for I suspected that I was going the wrong way, and I could go no other. And I sometimes suspected that the middle land through which I traveled was in my head, a derangement from the terrible blow that one of the things gave me as he came in to kill me. And yet there are correlates that convince me it was a real place.

Читать дальше

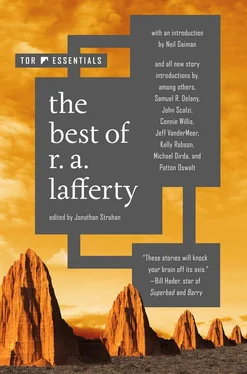

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)