The writing was wonderful, the characters inventive, the tone perfectly balanced between wryness and passion, the kind of passion that annihilates. I could not get it out of my head.

A few years later, a different one of my graduate-school professors, who’d become a friend, told me how much he admired R. A. Lafferty. He gave me a bound, uncorrected page-proof copy of Iron Tears, the 1992 Lafferty collection from Edgewood Press (I still have this volume, too). I thanked him, but my main reaction was indignation that the fifteen stories in the volume didn’t include “Continued on Next Rock.”

My admiration for the story, which I just read yet again, has only grown. After all, Anteros’s love poems are, if nothing else, unique: “You are the freedom of wild pigs in the sour-grass, and the nobility of badgers. You are the brightness of serpents and the soaring of vultures. You are passion of mesquite bushes on fire with lightning. You are serenity of toads.”

As I said—unique courtship poetry. And how come no man has ever told me that I am the nobility of badgers, let alone the serenity of toads? Why not, I ask you?

Maybe if I could have done the things that Magdalen could …

Up in the Big Lime country there is an up-thrust, a chimney rock that is half fallen against a newer hill. It is formed of what is sometimes called Dawson sandstone and is interlaced with tough shale. It was formed during the glacial and recent ages in the bottom lands of Crow Creek and Green River when these streams (at least five times) were mighty rivers.

The chimney rock is only a little older than mankind, only a little younger than grass. Its formation had been up-thrust and then eroded away again, all but such harder parts as itself and other chimneys and blocks.

A party of five persons came to this place where the chimney rock had fallen against a still-newer hill. The people of the party did not care about the deep limestone below: they were not geologists. They did care about the newer hill (it was man-made) and they did care a little about the rock chimney; they were archeologists.

Here was time heaped up, bulging out in casing and accumulation, and not in line sequence. And here also was striated and banded time, grown tall, and then shattered and broken.

The five party members came to the site early in the afternoon, bringing the working trailer down a dry creek bed. They unloaded many things and made a camp there. It wasn’t really necessary to make a camp on the ground. There was a good motel two miles away on the highway; there was a road along the ridge above. They could have lived in comfort and made the trip to the site in five minutes every morning. Terrence Burdock, however, believed that one could not get the feel of a digging unless he lived on the ground with it day and night.

The five persons were Terrence Burdock, his wife Ethyl, Robert Derby, and Howard Steinleser: four beautiful and balanced people. And Magdalen Mobley who was neither beautiful nor balanced. But she was electric; she was special. They rouched around in the formations a little after they had made camp and while there was still light. All of them had seen the formations before and had guessed that there was promise in them.

“That peculiar fluting in the broken chimney is almost like a core sample,” Terrence said, “and it differs from the rest of it. It’s like a lightning bolt through the whole length. It’s already exposed for us. I believe we will remove the chimney entirely. It covers the perfect access for the slash in the mound, and it is the mound in which we are really interested. But we’ll study the chimney first. It is so available for study.”

“Oh, I can tell you everything that’s in the chimney,” Magdalen said crossly. “I can tell you everything that’s in the mound too.”

“I wonder why we take the trouble to dig if you already know what we will find,” Ethyl sounded archly.

“I wonder too,” Magdalen grumbled. “But we will need the evidence and the artifacts to show. You can’t get appropriations without evidence and artifacts. Robert, go kill that deer in the brush about forty yards northeast of the chimney. We may as well have deer meat if we’re living primitive.”

“This isn’t deer season,” Robert Derby objected. “And there isn’t any deer there. Or, if there is, it’s down in the draw where you couldn’t see it. And if there’s one there, it’s probably a doe.”

“No, Robert, it is a two-year-old buck and a very big one. Of course it’s in the draw where I can’t see it. Forty yards northeast of the chimney would have to be in the draw. If I could see it, the rest of you could see it too. Now go kill it! Are you a man or a mus microtus ? Howard, cut poles and set up a tripod to string and dress the deer on.”

“You had better try the thing, Robert,” Ethyl Burdock said, “or we’ll have no peace this evening.”

Robert Derby took a carbine and went northeastward of the chimney, descending into the draw forty yards away. There was the high ping of the carbine shot. And, after some moments, Robert returned with a curious grin.

“You didn’t miss him, Robert, you killed him,” Magdalen called loudly. “You got him with a good shot through the throat and up into the brain when he tossed his head high like they do. Why didn’t you bring him? Go back and get him!”

“Get him? I couldn’t even lift the thing. Terrence and Howard, come with me and we’ll lash it to a pole and get it here somehow.”

“Oh, Robert, you’re out of your beautiful mind,” Magdalen chided. “It only weighs a hundred and ninety pounds. Oh, I’ll get it.”

Magdalen Mobley went and got the big buck. She brought it back, carrying it listless across her shoulders and getting herself bloodied, stopping sometimes to examine rocks and kick them with her foot, coming on easily with her load. It looked as if it might weigh two hundred and fifty pounds; but if Magdalen said it weighed a hundred and ninety, that is what it weighed.

Howard Steinleser had cut poles and made a tripod. He knew better than not to. They strung the buck up, skinned it off, ripped up its belly, drew it, and worked it over in an almost professional manner.

“Cook it, Ethyl,” Magdalen said.

Later, as they sat on the ground around the fire and it had turned dark, Ethyl brought the buck’s brains to Magdalen, messy and not half-cooked, believing that she was playing an evil trick. And Magdalen ate them avidly. They were her due. She had discovered the buck.

If you wonder how Magdalen knew what invisible things were where, so did the other members of the party always wonder.

“It bedevils me sometimes why I am the only one to notice the analogy between historical geology and depth psychology,” Terrence Burdock mused as they grew lightly profound around the campfire. “The isostatic principle applies to the mind and the under-mind as well as it does to the surface and under-surface of the Earth. The mind has its erosions and weatherings going on along with its deposits and accumulations. It also has its up-thrusts and its stresses. It floats on a similar magma. In extreme cases it has its volcanic eruptions and its mountain building.”

“And it has its glaciations,” Ethyl Burdock said, and perhaps she was looking at her husband in the dark.

“The mind has its hard sandstone, sometimes transmuted to quartz, or half-transmuted into flint, from the drifting and floating sand of daily events. It has its shale from the old mud of daily ineptitudes and inertias. It has limestone out of its more vivid experiences, for lime is the remnant of what was once animate: and this limestone may be true marble if it is the deposit of rich enough emotion, or even travertine if it has bubbled sufficiently through agonized and evocative rivers of the under-mind. The mind has its sulfur and its gemstones—” Terrence bubbled on sufficiently, and Magdalen cut him off.

Читать дальше

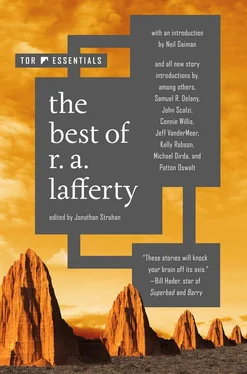

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)