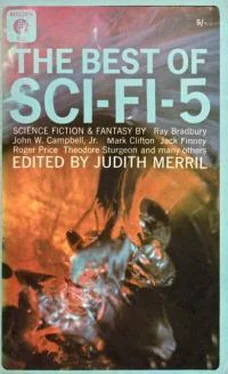

The Best of Sci-Fi-5

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1966, Издательство: Mayflower-Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Best of Sci-Fi-5

- Автор:

- Издательство:Mayflower-Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1966

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Best of Sci-Fi-5: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Best of Sci-Fi-5 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Best of Sci-Fi-5», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But the yarn was not over for me. What purpose to action if, beyond giving some release to the manic-depressive, it has no meaning? In the middle of it all, the answer to the goonie puzzle had hit me. But the answer solved nothing; it served only to raise much larger questions.

At home that night I slept badly, so fitfully that Ruth grew worried and asked if there was anything she could do.

“The goonie,” I blurted out as I lay and stared into the darkness. “That first hunting party. If the goonie had run away, they would have given those hunters, man, the chase he needed for sport. After a satisfactory chase, man would have caught and killed the goonie down to the last one. If it had hid, it would have furnished another kind of chase, the challenge of finding it, until one by one all would have been found out, and killed. If it had fought, it would have given man his thrill of battle, and the end would have been the goonie’s death.”

Ruth lay there beside me, saying nothing, but I knew she was not asleep.

“I’ve always thought the goonie had no sense of survival,” I said. “But it took the only possible means of surviving. Only by the most complete compliance with man’s wishes could it survive. Only by giving no resistance in any form. How did it know, Ruth? How did it know? First contact, no experience with man. Yet it knew. Not just some old wise ones knew, but all knew instantly, down to the tiniest cub. What kind of intelligence—?”

“Try to sleep, dear,” Ruth said tenderly. “Try to sleep now. We’ll talk about it tomorrow. You need your rest. …”

We did not talk about it the next day. The bigger questions it opened up for me had begun to take form. I couldn’t talk about them. I went about my work in a daze, and in the later afternoon, compelled, drawn irresistibly, I asked the goonie team to take me again to Carson’s Hill. I knew that there I would be alone.

The glade was empty, the grasses were already lifting themselves upright again. The fixe had left a patch of ashes and blackened rock. It would be a long time before that scar was gone, but it would go eventually. The afternoon suns sent shafts of light down through the trees, and I found the spot that had been my favorite twenty years ago when I had looked out over a valley and resolved somehow to own it.

I sat down and looked out over my valley and should have felt a sense of achievement, of satisfaction that I had managed to do well. But my valley was like the ashes of the burned-out fire. For what had I really achieved?

Survival? What had I proved, except that I could do it? In going out to the stars, in conquering the universe, what was man proving, except that he could do it? What was he proving that the primitive tribesman on Earth hadn’t already proved when he conquered the jungle enough to eat without being eaten?

Was survival the end, and all? What about all these noble aspirations of man? How quickly he discarded them when his survival was threatened. What were they then but luxuries of a self-adulation which he practiced only when he could safely afford it?

How was man superior to the goonie? Because he conquered it? Had he conquered it? Through my ranching, there were many more goonies on Libo now than when man had first arrived. The goonie did our work, we slaughtered it for our meat. But it multiplied and throve.

The satisfactions of pushing other life-forms around? We could do it. But wasn’t it a pretty childish sort of satisfaction? Nobody knew where the goonie came from, there was no evolutionary chain to account for him here on Libo; and the pal tree on which he depended was unlike any other kind of tree on Libo. Those were important reasons for thinking I was right. Had the goonie once conquered the universe, too? Had it, too, found it good to push other life-forms around? Had it grown up with the universe, out of its childish satisfactions, and run up against the basic question: Is there really anything beyond survival, itself, and if so, what? Had it found an answer, an answer so magnificent that it simply didn’t matter that man worked it, slaughtered it, as long as he multiplied it?

And would man, someday, too, submit willingly to a new, arrogant, brash young life-form—in the knowledge that it really didn’t matter? But what was the end result of knowing nothing mattered except static survival?

To hell with the problems of man, let him solve them. What about yourself, MacPherson? What are you trying to avoid? What won’t you face?

To the rest of man the goonie is an unintelligent animal, fit only for labor and food. But not to me. If I am right, the rest of man is wrong—and I must believe I am right. I know.

And tomorrow is slaughtering day.

I can forgive the psychologist his estimation of the goonie. He’s trapped in his own rigged slot machine. I can forgive the Institute, for it is, must be, dedicated to the survival, the superiority, of man. I can forgive the Company— it must show a profit to its stockholders or go out of business. All survival, all survival. I can forgive man, because there’s nothing wrong with wanting to survive, to prove that you can do it.

And it would be a long time before man had solved enough of his whole survival problem to look beyond it.

But I had looked beyond it. Had the goonie, the alien goonie, looked beyond it? And seen what? What had it seen that made anything we did to it not matter?

We could, in clear conscience, continue to use it for food only so long as we judged it by man’s own definitions, and thereby found it unintelligent. But I knew now that there was something beyond man’s definition.

All right. I’ve made my little pile. l can retire, go away. Would that solve anything? Someone else would simply take my place. Would I become anything more than the dainty young thing who lifts a bloody dripping bite of steak to her lips, but shudders at the thought of killing anything?

Suppose I started all over, on some other planet, forgot the goonie, wiped it out of my mind, as humans do when they find reality unpleasant. Would that solve anything? If there are definitions of intelligence beyond man’s own, would I not merely be starting all over with new scenes, new creatures, to reach the same end?

Suppose I deadened my thought to reality, as man is wont to do? Could that be done? Could the question once asked, and never answered, be forgotten? Surely other men have asked the question: What is the purpose of survival if there is no purpose beyond survival?

Have any of the philosophies ever answered it? Yes, we’ve speculated on the survival of the ego after the flesh, that ego so overpoweringly precious to us that we cannot contemplate its end—but survival of ego to what purpose?

Was this the fence across our path? The fence so alien that we tore ourselves to pieces trying to get over it, go through it?

Had the goonies found a way around it, an answer so alien to our kind of mind that what we did to them, how we used them, didn’t matter—so long as we did not destroy them all? I had said they did not initiate, did not create, had no conscience—not by man’s standards. But by their own? How could I know? How could I know?

Go out to the stars, young man, and grow up with the universe!

All right! We’re out there!

What now, little man?

ME

by Hilbert Schenck, Jr.

from Fantasy and Science Fiction

Me

I think that I shall never see

A calculator made like me.

A me that likes Martinis dry

And on the rocks, a little rye.

A me that looks at girls and such,

But mostly girls, and very much.

A me that wears an overcoat

And likes a risky anecdote.

A me that taps a foot and grins

Whenever Dixieland begins.

They make computers for a fee,

But only moms can make a me.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Best of Sci-Fi-5» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.